[UPDATED 3:15 pm with Under Secretary Work’s comments] CRYSTAL CITY: The automatic budget cuts known as sequestration aren’t the only nightmare scenario looming in March for the Department of Defense, Navy Secretary Ray Mabus said this morning. If Congress keeps on funding the federal government on the current ad hoc basis, by simply extending the current “continuing resolution” — now set to expire March 27 — instead of by finally passing proper appropriations bills, the impact would be equally bad.

[UPDATED 3:15 pm with Under Secretary Work’s comments] CRYSTAL CITY: The automatic budget cuts known as sequestration aren’t the only nightmare scenario looming in March for the Department of Defense, Navy Secretary Ray Mabus said this morning. If Congress keeps on funding the federal government on the current ad hoc basis, by simply extending the current “continuing resolution” — now set to expire March 27 — instead of by finally passing proper appropriations bills, the impact would be equally bad.

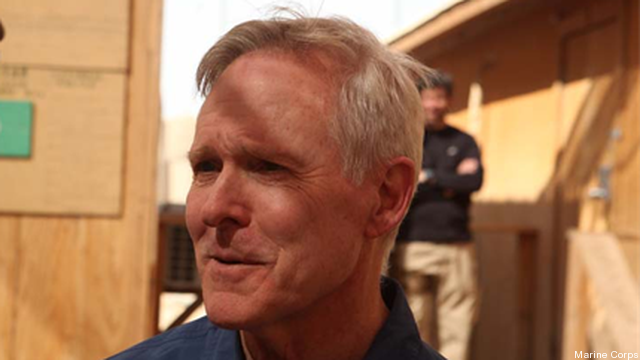

“Most of the attention is put on sequestration because it was such a big deal leading up to the fiscal cliff,” Mabus told reporters after his public remarks at the Surface Navy Association’s annual conference. “We have an equal, equal concern about CR.”

Asked about remarks earlier in the conference by uniformed leaders that the Navy was sailing for a readiness crisis — the infamous “hollow force” — Mabus said, “I agree with Adm. Gortney that if these things are triggered, in the sort of mindless automatic way they work, you do run a big risk of becoming hollow.”

[Updated: Speaking later at the same conference, Mabus’s Under Secretary, the gloriously outspoken Robert Work, said it was entirely possible that both disasters might strike at once. “We are planning as if sequestration occurs and a year-long CR occurs,” he said. “If that happens, ladies and gentlemen, the world as we know it will end. There’s just no way you can keep the Navy whole and keep the Marine Corps whole.”

[If he had to guess, Work went on, “we’re going to get some type of deal that take sequestration off the table, but we’re going to have a year-long CR.”]

Either disaster would have an equal financial impact on the Navy, but it would be distributed in different ways.

Sequestration “would be $4.6 billion hit for the Department of the Navy,” said Mabus in his speech. “If that continuing resolution is extended for the rest of the fiscal year that’s another — exactly the same number — $4.6 billion hit.”

The second similarity is “the mindless way both those things operate,” Mabus continued. “Under sequestration, you just whack a certain percentage off virtually every program. Continuing resolution says you stay at the levels you were at last year and no new starts.”

A memo last week from Deputy Defense Secretary Ash Carter instructed the services to prepare for sequestration by economizing on readiness, including — if sequester takes effect — cancelling the “availabilities” of Navy warships for major maintenance in port. But a continuing resolution only allows the government to keep spending on existing programs, not to start new ones (unless Congress makes a specific exception), and each “availability” is technically a new program unto itself.

So the CR would have exactly the same crippling impact on maintenance as the sequester, Mabus explained to Breaking Defense: “If you put a ship in for a shipyard availability, that may be considered a new start, and so we couldn’t do that.”

That said, the two disasters aren’t identical. Sequestration has its own unique and nasty wrinkles for the Navy. For example, the sea service has pushed hard for multi-year procurement contracts, in which it guarantees contractors the same amount every year for several years running in return for a lower overall price. Such steady-state expenditures are allowed under a continuing resolution. But sequestration cuts multi-year payments by the same amount it does almost all other programs, about 8.8 percent, which means the Navy couldn’t pay the whole sum. That, in turn, would violate the contract and send everyone back to the bargaining table. So, said Mabus to reporters, “if we can’t pay under sequestration, we breach a multi-year and the price just goes through the roof.”

The Navy Secretary wasn’t the only senior defense official bemoaning the current budgetary state of the United States early today. The head of Air Force Space Command, Gen. William Shelton, told reporters that the absence of a 2013 appropriations bill adds to the uncertainty engendered by sequestration. “That affects the planning for 2014 and that affects the planning for 2015, which we are deep into,” Shelton said at a breakfast put on by the Defense Writers Group. So far, the general said readiness has not been affected. “Day to day we are carrying on,” but he made clear that the Air Force would soon have to pare back or forgo flying hours, purchases of information technology, office furniture and the like.

Mabus made clear that he understood that budget cuts are probably coming no matter what, even if Congress and the White House cut a deal to avert sequestration. But rather than sequestration’s automatic cuts to every program or a continuing resolution’s auto-pilot continuation of last year’s spending levels, he begged political leaders to give the military discretion of how to apply the cuts: Give us a bill, he said, and let us figure out how to pay it so we can protect our priorities.

“Nobody likes budget cuts, but if Defense or the Navy has to be a part of some … grand bargain,” Mabus told the audience at the Surface Navy conference, “then give us the top line, let us manage how any cuts , how any reductions, are made. Let us put dollars against strategy instead of simply cutting the top line.”

Beset just a few years ago by out-of-control shipbuilding costs on programs like the Littoral Combat Ship, the Navy has vastly improved its management, Mabus argued. “We have shown, I believe pretty decisively so, that we know how to manage the budget, that we know how to set some priorities, that we know how to get money into programs, that we know how to drive a hard bargain, that we know how to get the most money for the taxpayers’ dollars,” he said. “Instead of mindlessly cutting, give us that chance to manage to whatever the final number is.”

“We’ve shown,” he said, “that we’re willing to make some pretty hard choices, that we’re willing to cancel some stuff.”

Mabus mentioned both shipbuilding and maintenance as priorities he wanted to protect. But what else is left to cut?

“I learned a long time ago,” said the veteran politician in answer to Breaking Defense, “I only get in trouble when I answer what-if questions.”

[Updated: Under Secretary Work was far more direct, as is his wont: “Shipbuilding is the No. 1 priority in the Department of the Navy. If given a choice between an aviation program and a shipbuilding program, the Secretary will choose shipbuilding.”]

Any specifics now would just inflame key programs’ partisans in Congress. But there’s the rub: Sequestration and the continuing resolution may be mindless, but precisely for that reason they save political leaders from making painful choices. The sequester law actually allows the President’s Office of Management and Budget to submit an alternative proposal for how to achieve the required cuts, while Congress can exempt any program it wishes from the restrictions of the CR — but either way requires sacrificing some constituency’s favorite program to save another’s, and it requires legislators to step up and vote to do so. America’s political class may no longer have the courage — and there’s no one left to beat it into them.

Major trends and takeaways from the Defense Department’s Unfunded Priority Lists

Mark Cancian and Chris Park of CSIS break down what is in this year’s unfunded priority lists and what they say about the state of the US military.