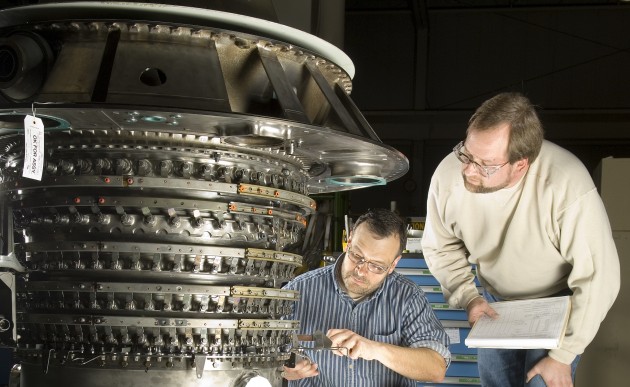

- Technicians work on a Pratt & Whitney 2000 engine, used by both commercial and military aircraft.

WASHINGTON: Close bases. It’s often good for the local economy. Yes, sequester’s a disaster and the federal government is gridlocked. But as a country, “we’re still kicking ass in a lot of areas,” Brookings Institution expert Michael O’Hanlon told me this morning. And bases are an area where the Pentagon can help.

“One thing we didn’t really get to [in the public discussion] is base closures need to be thought of a little differently,” O’Hanlon told me after a panel on “the American recovery and the defense industry” at Brookings this morning. Message to Congress on base closures: “Some metropolitan economies and regional economies may want them.”

In past rounds of base realignment and closure (BRAC), O’Hanlon noted, many local economies (not all) actually did better in the long run after their base shut down. Federal grants to ease the transition helped, but more fundamental was innovative repurposing of former military facilities and real estate into industrial parks, recreational parks, community colleges, and so on. In a post-recession economy driven by bottom-up alliances of local governments, the private sector, and civic groups — what Brookings’ Bruce Katz calls the “Metropolitan Revolution” — there are ever-more metro areas that could find alternative uses for a closed military base that would more than outweigh the loss of federal dollars.

The current base-closure process is all about damage control: BRAC tries to cut the Pentagon’s infrastructure costs as much as possible while harming local economies as litle as possible. In the future, O’Hanlon argued, we need to also look at base closure as a way to create opportunities for economic growth. In general, Washington policymakers need to approach defense reform “with a little more of a spirit of optimism and confidence… than we usually manifest in this town.”

Not that local governments and businesses are waiting on Washington, Bruce Katz told the audience at Brookings. “The US is essentially at the cutting edge of a huge devolution revolution,” said Katz. He’s director of Brookings’ Metropolitan Policy Program, which works with metro areas around the country “helping them understand how to move forward in the absence of federal leadership.” After decades of federal funds driving research, development, and higher education, he argued, cities, companies, and colleges are working together to move ahead without the feds.

“The good news is that manufacturing is driving this recovery,” Katz said. While manufacturing only makes up 13 percent of the US economy — prompting talk of the US as a “post-industrial” nation — it has generated 37 percent of recent growth, Katz calculates, a boom driven both by cheap energy at home (US natural gas prices have dropped 85 percent since 2008) and weaker competition overseas (Chinese wages have risen 71 percent since ’08).

Manufacturing, in turn, is a sector in which the Defense Department has a lively interest. Both commercial industry and defense industry increasingly require skilled workers educated in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (aka STEM). Both want to move rapidly from concept to prototype to mass production, whether the product is an armored vehicle for the military, a mobile phone for civilians, or new cybersecurity defenses for both.

“I think there’s something to teach each other,” Katz said.

In some cases, of course, defense and commercial industry combine in the same company. Traditional war machines are a specialized and segregated industrial base: The “Big Five” US shipyards work almost exclusively for the Navy, while the nation’s last factory capable of making main battle tanks (in Lima, Ohio) is government-owned. But other sectors, such as aerospace, have considerable cross over.

“We’re 25% military, 75% commercial,” Pratt & Whitney vice-president Jay DeFrank reminded me as we talked after the panel. P&W makes jet engines for both civilian and military aircraft. Indeed, it often makes variants of the same engine for airliners and military transports. While supersonic fighters require special components and designs, those are still built on the same technology.

Even when the civilian and military markets demand very different products, DeFrank told me, the same advanced manufacturing techniques can apply. “There’s a big exchange in terms of manufacturing practices, things like additive manufacturing, composites, closed cell manufacturing, [and] process management techniques,” he said. Pratt & Whitney had taken many cues from, for example, Japanese car makers. Conversely, he argued, when P&W sends engineers out to advise its thousands of suppliers, those advisors inject technical expertise into local companies that helps their competitiveness in both defense and commercial markets.

So can states, cities, companies, and colleges grow the economy faster from the bottom up than federal gridlock and sequestration can rot it from the top down?

“Sequestration is really troubling to me because it means that the national government is incapable of making choices and setting priorities,” Katz admitted. But as localities and states move ahead on their own, they’ll pressure lawmakers to get past the gridlock and just help them, whether by providing them federal grants or just getting regulation of their way. “At some point,” Katz said confidently, “parochialism will trump partisanship.”

But there is no alternative to federal leadership in the defense sector. State and local governments buy no tanks, warships, or fighter aircraft (fortunately) and only a modest number of helicopters and small arms for law enforcement. Private sectors will invest in cybersecurity improvements from which the military can also benefit, but they will not invest in cyber offense (again, fortunately). So if Washington doesn’t reform defense from the top down, there’s no one else to do it from the bottom up.

Some of the most urgently needed reforms are the most politically toxic. Base closures are a prime example, and O’Hanlon’s optimism about them has not caught on. So are measures to contain the growing costs of military compensation, not only salaries but, to a far greater extent, the rapidly rising bills for retirement pay and for healthcare provided through the Pentagon’s TRICARE program.

“DoD proposed almost a decade ago increasing the premiums, copays, and deductibles for TRICARE, especially for retirees,” said Nelson Ford, who held several senior Pentagon positions under President George W. Bush. The Obama administration has proposed the same reforms and met with the same resounding rejection from the Congress. Today, Ford told the audience at Brookings, as a retired federal employee, he pays about $8,000 a year for his family’s health insurance, while a retired military officer pays about $800.

Many legislators see generous benefits as a sacred compact with those who risk their lives for the rest of us, added panelist MacKenzie Eaglen, but “we actually have two contracts with America’s military.” One is providing the best possible benefits to make their lives less difficult; the other is providing the best training, technology, and equipment to make sure they live to collect those benefits. As personnel costs skyrocket and the budget gets sequestered, she said, “one is coming at the expense of the other.”

(Eaglen, an American Enterprise Institute scholar and frequent BreakingDefense contributor, wrote about this dilemma in depth for us last month).

If personnel costs cut deeply into weapons and training, added Ford, who has three children on active duty, it “could put at risk my children who are in the line of fire.”

That’s a problem only Washington can solve — but there are no signs it will any time soon.

Edited 10:35 am, Wednesday to correct “additive composites” to “additive manufacturing [and] composites.”

Major trends and takeaways from the Defense Department’s Unfunded Priority Lists

Mark Cancian and Chris Park of CSIS break down what is in this year’s unfunded priority lists and what they say about the state of the US military.