http://youtu.be/AMyoQhUcPgM

This summer, the US Army’s research & development command, RDECOM, has kicked off an experiment to try infusing the latest commercial video game technology into the Army’s most important combat simulator. The new tech brings real potential for better military training – but also a very real danger.

Famous for powering games like 2012’s Borderlands 2 and XCOM: Enemy Unknown, Epic Games, Inc.’s award-winning Unreal Engine is already used for military software ranging from medical simulators to the free game/recruiting tool America’s Army. But what the Army wants to do this time is much more ambitious. It wants to use the latest version of the software, Unreal Engine 3, to improve the revolutionary but still somewhat stilted Dismounted Soldier Training System. Unlike earlier simulators that trained aircraft pilots in mock cockpits or tank crews in dummy vehicles, DSTS is the Army’s first attempt at immersive virtual reality for ordinary infantrymen – who after all suffer the vast majority of casualties in war.

![Capt. Marcus Long, 157th Infantry Brigade operations officer, First Army Division East, takes advantage of the Dismounted Soldier Training System. The helmet-mounted display provides a realistic virtual training platform programmable for any theater [ http://www.army.mil/article/97582/ ]](https://breakingdefense.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2013/08/DSTS-single-soldier.jpg)

Army Capt. Marcus Long geared up to use the Dismounted Soldier Training System (DSTS).The stakes are high, and the potential problems go far beyond the technological to fundamental questions of funding and policy. As budgets tighten, the Army has cut back expensive field training and turned more and more to simulators, often inspired by civilian computer games such as World of Warcraft. Just this year, the automatic budget cuts known as sequestration – which Congress and the White House seem utterly unable to turn off – have forced the service to cancel major training exercises for 78 percent of Army combat brigades.

The Army’s intent is for the improved simulators to supplement traditional live training, giving soldiers a chance to rehearse the basics over and over on base before they head out to a field exercise. The Army’s temptation, however, is to use simulators to replace live training. After all, if the sims are so great, it’s easy to rationalize cutting expensive field exercises more and more. But there are some things virtual reality just can’t teach you – and some things it may even teach you wrong.

Certainly, the Dismounted Soldier Training System, built by immodestly named contractor Intelligent Decisions, is an impressive piece of technology. (There’s a great series of pictures online – which we don’t have the rights to reproduce, unfortunately – starting here). It puts a full nine-man infantry squad together in a room, all wearing wirelessly networked VR headsets that give each soldier his own point of view on the same virtual environment.

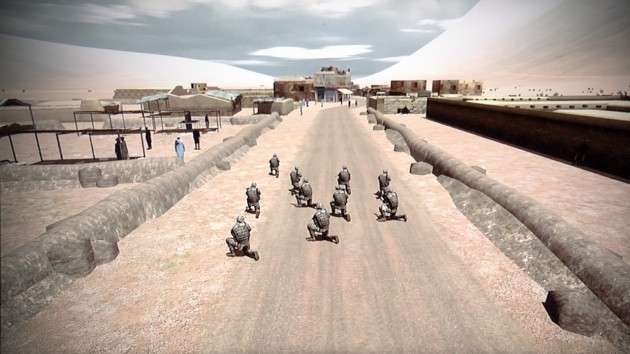

![Soldiers of the 157th Infantry Brigade, First Army Division East, take advantage of the Dismounted Soldier Training System. The DSTS provides a realistic virtual training platform programmable for any theater of operations while mitigating risk to... [ http://www.army.mil/article/97582/ ]](https://breakingdefense.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2013/08/DSTS-entire-squad-together-630x349.jpg)

Up to nine soldiers can use DSTS to train together as a squad.

DSTS can even do things that traditional field training can’t because they’re too complex, too expensive, or just too dangerous to do in real life. DSTS can subject soldiers to virtual bombardments that can blow their avatars apart, whereas field exercises are limited to scary but harmless special effects. DSTS can rapidly run and re-run soldiers through different range of scenarios in different locations, whereas real-world training ranges can take weeks or months to build and hours to reset after each run. DSTS can instantly generate computer-controlled enemies and civilians, instead of exercise organizers having to dedicate troops to an “opposing force” (OPFOR) and hire civilian role-players.

What the Army’s Research, Development, and Engineering Command (RDECOM) and Intelligent Design want to accomplish by licensing the Unreal Engine is to make the avatars simulate a wider, more flexible, and more realistic range of behavior. The Bohemia Interactive Simulations-designed Virtual Battlespace 2 (VBS2) software that currently runs DSTS, for example, can use motion sensors on each soldier’s body – a bit like a militarized Nintendo Wii – to tell if he’s standing, kneeling, or lying prone; Unreal could add the ability to crouch, which is actually the most common stance soldiers take under fire in real life. VBS2 lets soldiers shoot targets, throw grenades, and open doors; Unreal lets them switch weapons, pick up objects, and kick doors in. Perhaps most important, said Pape, “we’re making the avatars smarter”: Unreal will give the computer-controlled enemies and civilians a much wider and less rigidly pre-defined array of responses to what the human players do.

Two computer-controlled “avatars”: an enemy combatant (left) and a civilian (right).

But there still will be strict limits on how real the virtual reality gets. To start with, DSTS can’t get soldiers wet or muddy, cold or hot, nor can it expose them to the smells of gunpowder and burning buildings. It’s not technically impossible, said Pape: “Those capabilities exist; they’re not part of the program right now.”

More problematic is how the soldiers “move” through the virtual reality. Putting all nine soldier on treadmills would cost an estimated quarter of a million dollars per DSTS. Instead, said Pape, “all of the soldiers stand on a 3’-by-3’ rubber pad to provide them haptic feedback” – basically, vibration – “so they don’t run into each other.” So rather than actually walking, crawling, or running, the soldiers move their avatars around by using a hand controller attached to their training “weapon.”

To start with, that means soldiers don’t get tired and sore in the simulator the way they would in the field. But using hand controls to move is worse than unrealistic: It’s potentially dangerous. There’s such a thing as muscle memory, and a soldier who has repeatedly practiced running for cover by tweaking a mini-joystick may be just a little too slow to use his legs when someone shoots at him for real. Even minor differences between the training environment and real combat can cause big problems. Police departments across the country, for example, changed their firearms training after they realized that officers were wasting time in real-life firefights by picking up spent brass cases from their revolvers or pocketing empty magazines from their semi-automatic pistols, things they had done over and over and over on the firing range. Any combat training that teaches soldiers to stay in a three-foot circle is deeply problematic.

Virtual reality is getting more realistic all the time, and it has tremendous potential to improve military training. But its limitations make it no substitute for getting tired, sore, and muddy out in the field. No matter what the budget cutters may say, real-life training is worth the price.

Head start: Early ’25 may be first flight for Black Hawk with T901 engine

Sikorsky is using remaining FARA dollars to test out the new T901 engine in anticipation of integrating it on a UH-60 M Black Hawk later this year.