US and Korean marines staged amphibious assaults like this in recent wargames, but massed attacks may be a thing of the past.

NATIONAL HARBOR: Cheap grey-market missiles and commercially available radar kits are forcing the Marines to reinvent amphibious warfare for the 21st century. The new Corps concept, Expeditionary Force 21, predicts long-range threats will force the fleet to stay at least 65 nautical miles offshore, a dozen times the distance that existing Marine amphibious vehicles are designed to swim. The ramifications are just beginning to ripple across tactics and technology, starting with a radical overhaul of the Marines’ Amphibious Combat Vehicle program and a new emphasis on high-speed landing craft.

As longer-ranged precision weapons proliferate to potential adversaries around the world, “we’ve moved from the high-water mark to 12 nautical miles [offshore] and now we’re at about 65 nautical miles,” said Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps, Lt. Gen. John Paxton, when I asked him about EF-21 after his public remarks at last week’s Sea-Air-Space conference.

“That’s the anticipated threat ring in the near- to mid-term,” Paxton told me. (Emphasis mine). “The range is going to continue to go further out.”

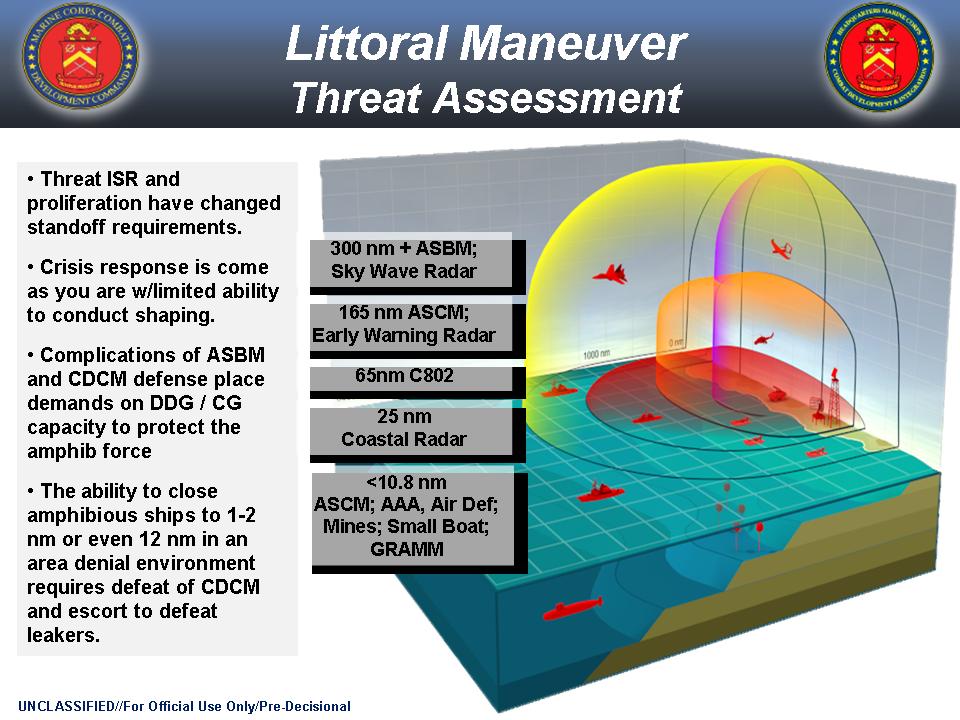

In fact, anti-ship cruise missiles can hit ships 165 nautical miles from shore, according to a Marine Corps briefing slide, while China’s still-in-development anti-ship ballistic missile can go at least 300 miles. (No figures yet on China’s prototype hypersonic missile). According to the slide, the 65-mile figure simply reflects the maximum range of the Chinese-made C-802 Silkworm.

A Marine Corps slide showing the modern threats to an amphibious landing force.

The C-802 is widely available — the Lebanese militia Hezbollah used one to cripple an Israeli corvette in 2006 — but it is hardly cutting-edge. Conversely, at closer ranges, even a low-end adversary without anti-ship missiles can get cheap sensors to find the fleet and direct, for example, swarm attacks by high-speed boats or even use artillery, precision-guided mortars, and anti-tank missiles.

Those sensors matter as much as the weapons, and they’re even more widely available, said retired Marine Col. Doug King, director of the Commandant’s “Ellis Group” of hand-picked thinkers: “You can buy a 25-nautical-mile radar; they’re everywhere.”

I did a Google search and a commercial brochure on just such a radar was my first result: “Now you can see crystal clear targets up to 32 nautical miles away.” The radar weighs less than 17 pounds and I could have it shipped to me tomorrow for $1,999.

So a 65-mile standoff from shore is a general guideline, not a magic number, King said. It’s a safe rule of thumb to follow when “we’ve arrived on scene, we’re not certain of the A2/AD [anti-access/area denial] threat, and we need to put Marines ashore,” he said.

As threats proliferate, King told me, the Marine Corps face a choice:

“If the United States is in trouble or there’s a citizen that is in trouble… are we going to ‘shape’ that environment, [i.e.] basically defeat all the [threat] systems so we can come in close to the two miles or the 12 miles [from shore] that people thought of before, or are we going to respond to the crisis?” King said. Under Expeditionary Force 21, he said, “our goal — and we can do this today — is we can come from a greater distance.”

Expeditionary Force 21 will be updated every year. So how the Marines will keep changing the concept. But listening to Marine leaders like King makes two things clear:

- they don’t have any illusions that some magical safe zone lies beyond the 65-mile mark, and

- they won’t wait for US air, sea, and cyber power to blast a safe path to the shore.

Indeed, in at least some cases, they see small landing teams — much like the Marine Raiders of World War II — as the cutting edge of the joint force, slipping in by boat or V-22 aircraft to destroy key enemy sensors or anti-ship weapons so the larger force can approach.

“If the Navy’s unable to get closer in because of the threat, we just can’t sit there and wait,” Brig. Gen. William Mullen said at Sea-Air-Space. The challenge is getting Marines through the threat zone alive.

A V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor lands Marines in Afghanistan.

Wreaking Havoc — Within Limits

With current technology, “a few good men” can get ashore from more than 65 miles out. That’s enough Marines to rescue some US citizens, reinforce an embassy, or hit a key target and get out, but not enough to seize and hold ground. It would be less an amphibious assault and “more of a raid,” King told me.

Putting this first small force ashore doesn’t necessarily require blowing holes in the enemy’s layered defenses, just disrupting it at key times and places through stealth airstrikes or cyber attack. “[E.g.] for this eight-hour window, I can fly this route — I don’t need to keep it open all day, I need to create a window of opportunity to put that company ashore,” King said. “Once they’re ashore, they’ll wreak havoc.”

The force would probably a single company of a hundred-plus Marines slipping ashore from a boat or flying in on a V-22 aircraft. But while the Marines are developing “internally transportable vehicles” that can fit inside a V-22, most of the Marines in such a company-sized force would still have to walk, which limits both their maneuvers and their ability to carry heavy weapons.

“65 to 100 miles out….there’s no way we do an entire amphibious landing from that type of distance,” Brig. Gen. Mullen told the Sea-Air-Space conference when I raised the question. “It’s not possible, it’s not feasible, we can’t go do a build-up at an operationally relevant pace.”

Shutting aircraft or landing craft back and forth over a 65-plus-mile distance takes too long to get Marines ashore in numbers with vehicles, heavy weapons, and supplies. “Once you get closer, everything’s easier,” said Mullen.

So the mission for the initial force is to start prying open the door — the traditional phrase “kick down the door” is too strong a term here — so the fleet can get closer and more Marines with more heavy equipment can land. A Marine company could seize a small island outpost where the enemy had emplaced radars and missiles, hunt down launchers that had eluded airstrikes or secure a modest landing site on the mainland: “not a 1,000-yard beach but a place where we can maneuver an LCAC [hovercraft] or a landing craft ashore,” said King.

This second wave could bring in more Marine riflemen, light armored transports like the proposed “Phase I” Amphibious Combat Vehicle (aka ACV 1.1) to let them maneuver faster, or an air-defense battery to protect the mini-beachhead. As the force built up, the scattered individual companies could link up into a battalion — which will require robust but portable new communications networks that can coordinate far-flung units with each and with the fleet 65 miles out in the face of enemy jamming and hacking.

Only once the first small force of Marines — along with airstrikes by F-35s and other planes, jammers like the EA-18G Growler, and cyber-attacks — have wreaked sufficient “havoc” on the enemy’s defenses can the fleet come in close enough to launch the main assault. Even so, said King, the ships will probably stay 30 to 50 nautical miles offshore rather than approach to the traditional five to 12 miles, which is within the range of too many shore-based weapons.

Aging Navy LCAC hovercraft like this one carry Marine vehicles, supplies, and heavy equipment ashore.

The Connector Challenge

So how do you get ashore swiftly from such distances? The new tactics will require new technology — specifically better and faster “connectors,” to use the Navy/Marine lingo for landing craft. But instead of landing on the beach, the Marines now want their connectors to drop amphibious vehicles off five miles from land. That keeps the connectors out of range of ground troops with anti-tank missiles, for one thing. In fact, the fastest current connector, the Landing Craft Air Cushion (LCAC) hovercraft, is so lightly protected the Navy refuses to land it on any defended beach. But the LCAC and other current landing craft are designed to bring Marines all the way to the shore, not drop them off in the surf.

So what’s the solution? A short-term fix may simply be new ramps, said Mullen. The Marines want to modify current landing craft so an amphibious vehicle can drive straight into the water rather than waiting for the ramp to touch the beach. They’re even considering modifications to the ramp on the Joint High Speed Vessel, an ocean-going ship (albeit a small, short-ranged one), to let vehicles “launch in-stream” from a JHSV at sea.

Currently, the JHSV isn’t intended for amphibious assault at all: It’s based on a civilian high-speed ferry that unloads at piers and ports. Using such a large, fast vessel as a “mothership” for an amphibious assault would be a major step forward.

For now, the Navy is sticking to its current program to replace the current LCAC and Landing Craft Utility (LCU), and the Marines are looking at modifying those vessels, not some radical alternative. But, Mullen went on, “long-term, we need to identify some leap-ahead ‘connector after next’ ideas.”

One option being considered is called the Ultra-Heavy-Lift Amphibious Connector (UHAC), which would paddle through the water and then straight ashore on buoyant, air-filled tracks. Another is a semi-robotic high-speed sled that could carry a single Amphibious Combat Vehicle, drop it off in the water, and then find its own way back to the fleet.

But the Marines are eagerly seeking new ideas. They recently had a “connector summit” with Navy and private-sector representatives and will soon issue a formal Broad Area Announcement (BAA) of desired capabilities, Mullen said. Then, “[we’ll] see what comes back from industry in terms of feasibility.”

Some 75 years ago, an eccentric Louisiana boat-builder came up with the design for what would become the ubiquitous landing craft of World War II. “Andrew Higgins is the man who won the war for us,” said to D-Day commander Dwight Eisenhower. That’s the kind of innovation the Marine Corps needs from industry again.

Out of INF, Army deploys Typhon weapon to the Philippines

“This is a significant step in our partnership with the Philippines, our oldest treaty ally in the region,” said Brig. Gen. Bernard Harrington, commanding general of the 1st MDTF.