President Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping

WASHINGTON: New agreements between the US and China will reduce the risks of accidental war in the western Pacific. That’s good news — but don’t imagine for a minute that it changes the fundamentals of the competition.

Chinese president Xi Jinping’s summit deals with President Obama and Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe represent Xi’s tactical decision to dial down tensions, not any abandonment of China’s strategic goals. Xi’s not even ceasing all provocative actions, such as building airstrips in the disputed Spratly Islands of the South China Sea. What’s more, the protocols on military-to-military relations in particular not only help both countries prevent unplanned clashes: They also help Xi consolidate power over his own armed forces in a way no Chinese leader has for decades.

“There are probably many drivers Xi Jinping has for these agreements,” China scholar Bonnie Glaser told me when I approached her after a panel this morning at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “One is certainly to avoid any accident that could lead to escalation,” she said, “but [also] there is an attempt by Xi Jinping to ensure that the PLA is not creating potential problems.”

“It’s really not a problem of the PLA institutionally,” she emphasized: Communist Party civilians seem to have the generals under tight control. The problem, instead, is “individual operators” whose nationalistic passions might get away from them in the heat of the moment. Consider the Chinese escort vessel who nearly rammed the USS Cowpens for coming too close to China’s aircraft carrier, or the Chinese fighter pilot that did a dangerous barrel roll right over a US P-8 Orion reconnaissance plane. “This is something that Xi Jinping does not want to see reoccur, for good reason,” Glaser said. “These types of agreements signal any individual pilot or navy captain that you should not behave in a way that is dangerous.”

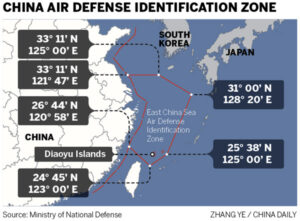

China’s new “Air Defense Identification Zone,” which covers the Japanese-controlled Senkaku Islands — called the Diaoyus by China.

That hardly means there won’t bel any provocations. It simply means there will be fewer provocations of which Xi Jinping didn’t approve. Xi definitely approved November’s unilateral declaration of an “air defense identification zone” (ADIZ) that covered areas disputed by both Japan (the Senkakus) and South Korea (Iedo). In past incidents, like the 2001 downing of an American EP-3 spy plane and the internment of its crew, elements of the Chinese military or other parts of the sprawling bureaucracy might go beyond Beijing’s intentions, said Kurt Campbell, former assistant secretary of State. Under Xi, assertive moves are more likely to be “coordinated at the very top levels,” he said at the CSIS panel. “They are not accidents.”

Throughout his career, “I sensed in much of my diplomacy with Chinese friends, until quite recently, some anxiety about how the military operates in the Chinese system,” Campbell said. “What Xi Jinping has demonstrated quite clearly is he’s comfortable giving orders, taking control….He is in charge of the military.”

The good news is that Xi has apparently decided to back off from confrontation — somewhat. “China recognizes that…they on a variety of fronts have taken steps that have created anxiety in their neighborhood and ultimately that anxiety is not in their strategic interest,” Campbell said.

Hence the new agreement between Xi and Obama. Interestingly, while it was the Americans who first pushed for formal protocols to keep military encounters from escalating, Xi “took ownership” of the idea and presented his own proposals at last year’s summit in Sunnylands, Calif., Glaser said. That Chinese proposal was the basis for the new agreement.

That said, the new agreement doesn’t have much new in it. On the question of each side telling each other about its military exercises, Glaser said, “the US and China have not agreed on advance notification.” Each side has agreed to notify the other about its wargames when it deems “appropriate,” but that conceivably could be long after the fact.

As for preventing accidental clashes, the only specific protocols in the agreement are those already established for surface ships, specifically the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea. (This represents something of a personal vindication for the Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. Jonathan Greenert, who’s campaigned hard to get China and other regional navies sign on to CUES). CUES currently applies only to naval vessels, however. It’s the Chinese coast guard that’s been most aggressive in disputed waters. Nor do the agreements so far cover encounters involving aircraft, which are much complex — for one thing, aircraft move much faster — although working them out is on the agenda.

So what’s significant in the Xi-Obama agreement is less the substance than the tone. That’s even more true of the joint statement from Xi and Japan’s Abe.

Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe

Japan & The Nationalism Problem

The new Sino-Japanese statement doesn’t begin to resolve the disputed status of the Senkaku Islands (the Diaoyus in Chinese). What it does is begin to ratchet down the rhetoric. Most important, Xi and Abe agreed to revive talks about setting up hotlines between their governments, especially their navies, that made real progress before they were suspended in 2012, said Glaser. Those who saw the faces of Xi and Abe when they met must realize just how much tension exists between the two countries. Both men looked as if they had been horsewhipped to get them to appear together in public.

“I’m hopeful we’ll see some progress in terms of managing these issues, but the underlying drivers and dynamics of the problem, I think, will persist,” Glaser said.

“The underlying dynamic is still one of concern, some masked antagonism, and very different views about the future,” Campbell agreed, “but I think we will likely go through a period, at least for the next year or so, where some of the most difficult issues will be muted.”

The third panelist, former deputy secretary of state Richard Armitage, was even less optimistic. “In the picture we saw in the paper [of Xi and Abe], they looked like they were smelling each other’s socks,” Armitage snarked. “It’s not going to improve in the next couple of years in a major way.

That’s especially true since next year is the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II: “It’s too good an opportunity for China to miss” to stir up anti-Japanese sentiment, Armitage argued. Until Chinese leaders feel sufficiently secure that they don’t need an external bogeyman, he said, the Chinese relationship with Japan won’t fundamentally change.

Conversely, Armitage continued, the Japanese public has soured on China in recent years — not because of Abe’s alleged nationalist tendencies but because of China’s own actions. Chinese often tell him “we’ve got a big Abe problem,” he recounted. “They’re wrong: They have a Japan problem now.”

Indeed, throughout the region, diplomats’ hands are tied by domestic politics and nationalist passion. “What we are seeing in Asia in particular is two paradigms in conflict right now,” Campbell said. All Western Pacific governments recognize their common interest in trade, stability, and open sea lanes, he argued. But there are rising nationalist pressures in the countries of the region, as well.

“My own experience is I’ve never worked on a set of issues where I’ve seen more white knuckles, in which senior diplomats recognized very clearly that a misstep on any of these issues would mean that they’d be out of a job, almost immediately,” Campbell said. “As a consequence there’s almost no flexibility across the board and the best that we can often do in certain circumstances is essentially try to put things on hold and export extremely difficult problems into the future.”

“The [US and Chinese] militaries are engaged in a very intense competition,” said Glaser. “The Chinese are developing capabilities that will make it more risky for the United States to operate within the first island chain [from Japan through Taiwan down to Malaya]. We call this anti-access/area denial, [and] the United States is working very hard to maintain access….This competition is going to continue.”

“If we can put in place measures to make accidents less likely, that’s a good thing,” she said. “I don’t think it’s going to solve the larger problem.”

No service can fight on its own: JADC2 demands move from self-sufficiency to interdependency

Making all-domain operations a warfighting capability means integrating, fusing, and disseminating a sensor picture appropriate for a particular theater segment, not all of them, says the Mitchell Institute’s David Deptula.