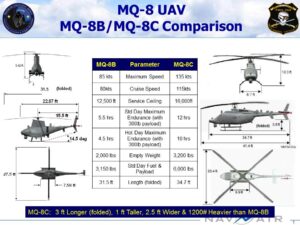

The older, smaller MQ-8B Fire Scout compared to the new and larger MQ-8C

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB: They get so big, so fast. Once a child-sized helicopter that could just collect reconnaissance imagery, the Navy’s MQ-8 Fire Scout has graduated to a bigger airframe that will also carry a maritime search radar and laser-guided rockets.

The tentative plan is to kick off the competition for the new radar with a formal Request For Proposals in the first quarter of (calendar year) 2015, the program manager told reporters here this morning. While the Navy as already tested a Telephonics radar on the smaller B-model — indeed, a radar-equipped B recently flew off a Coast Guard cutter — the bigger C-model could accommodate a larger and more powerful radar, so the service wants to explore its options, said Capt. Jeff Dodge.

The Fire Scout’s current suite of electro-optical and infrared (EO/IR) sensors is great for getting detail on a target and what it’s doing, Dodge said, but in the vastness of the ocean, radar’s usually required to find the target in the first place. Happily, the Fire Scout can carry both systems, even in the more cramped confines of the B model: the EO/IR sensors go in a “ball” under the fuselage, the radar in the nose. The one drawback is the added weight of the radar does reduce the aircraft’s range. But given that C can fly for 12 hours straight, more than twice the endurance of the B model, there’s plenty of range to play with.

Northrop Grumman’s second MQ-8C Fire Scout takes flight.

If you’re willing to reduce range a little further, you’ll soon be able to put a rocket pod on the Fire Scout. The B model has completed land-based testing with the BAE-built Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System (APKWS), which essentially takes the venerable and widely used 2.75″ diameter rocket and converts it into a precision-guided weapon. Now the program is waiting on a decision whether to proceed with at-sea testing of an armed B model. Dodge expects to start working on a larger APKWS rocket pod for the C model sometime in late 2015.

Even with rockets, however, Fire Scout is not an aircraft for high-threat environments, Dodge emphasized. “All helicopters — especially in the maritime environment — are low, slow, and exposed: there’s no terrain you can hide behind out there,” he said. In “major combat,” Navy helicopters in general play a defensive role, screening their motherships against fast attack boats and submarines. For Fire Scout in particular, though it’s been tested on a range of ships from frigates to destroyers, the primary carrier is intended to be the corvette-like Littoral Combat Ship, which isn’t built for the battle line.

“LCS is not going to be a part of a large surface action group that’s going to be engaged head to head, toe to toe with the enemy,” Dodge said. “We’re going to be the outskirts of that effort…building situational awareness for the commanders.”

Admittedly, the Littoral Combat Ship is changing. The Navy will build 32 to the current design, and these

The upgraded version of the LCS-1 Freedom class

“Flight Zero” LCS will often embark the Fire Scout configured for mine-clearing, with a specialized sensor called COBRA instead of the standard EO/IR sensor ball and a to-be-designed data relay to better link the LCS to its unmanned minesweepers. But the next 20 “small surface combatants” will be an upgunned LCS that drops the mine warfare mission to focus on anti-submarine and anti-ship warfare. Even with better weapons and a tougher hull, however, the new LCS will stick to skirmishing, scouting, and support missions rather than plunge into an enemy Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) defense.

Each LCS of whatever variety will typically embark a single manned MH-60 Sea Hawk helicopter and either a pair of the smaller Fire Scout Bs or a single C-model. Dodge argues this isn’t a net loss in capacity because the C can fly more than twice as long and will require half as many launches and landings, which are hard on both equipment and personnel.

With the two programs so intimately connected, the changes to LCS will trickle down to Fire Scout. The uncertainty in the one program is causing uncertainty in the other. “There’s a little bit of requirements churn,” Dodge said.

“We’re designing the system so it can go on any air-capable ship in the Navy,” he said, but only LCS deployments are in the current plan. “Our hands are full just getting LCS covered to meet those requirements [for testing]. We’re working for any LCS opportunities to get our program into IOT&E [initial operational testing and evaluation].”

Capt. Jeff Dodge

If an LCS isn’t available, the program will happily test aboard another ship, since the roll, pitch, and winds of at-sea testing are impossible to replicate on land. The C-model is being put through its paces on the Aegis destroyer Jason Dunham as you read this. “Yesterday, we had the first shipboard mission for the MQ-8C,” Dodge said. “We accomplished 22 landings and recoveries in just over three and a half hours.”

The hope is to have the C-model ready for a real-world deployment — what’s called Initial Operational Capability (IOC) — by late 2016, Dodge said, but whether the MQ-8Cs actually get to deploy on a ship that year depends on whether a ship is available. The Perry-class frigates that have carried most MQ-8B deployments to date are being retired faster than LCS can replace them.

Multi-ship amphib buy could net $900M in savings, say Navy, Marine Corps officials

Lawmakers gave the Navy authorities to ink a multi-ship amphib deal years ago, but the service has not utilized that power yet.