Nuclear modernization will receive at least $1.2 billion more this year than last year’s $23.5 billion if the president’s Defense Department budget request is approved. Modernization funding for nuclear weapons and their delivery systems comprise 4 percent of the defense budget and 0.6 percent of the Federal budget. These include : the Ohio-class submarine replacement program (ORP); a new long range bomber (LRSB); and a follow-on air launched cruise missiles (ALCM), as well as the ground-based strategic deterrent (currently the Minuteman missile system.)

Critics says that’s too much. They want to eliminate four of the ORPs while retiring four of the current submarines early and delaying by four years the procurement of the first new sub; delay buying the LRSB; cancel the ALCM and modernization of the ground-based cut upwards to allegedly save $75 billion over the next decade.

Are these reductions workable? Would they contribute to improving and enhancing our strategic deterrent, especially in terms of questions of stability and the future adequacy of our deterrent?

Reducing the fleet of strategic nuclear armed submarines to eight from the planned 12 submarines means over the next few decades as few as six submarines would be available at any one time. This would seriously degrade the US nuclear deterrent capabilities, leaving as few as two submarines on patrol at any one time.

This would dramatically reduce the ability of the US to hold at risk adversary targets. It would also require operation of the sub fleet at a much higher tempo, thus increasing their potential vulnerability and boosting their costs of operation.

Some have suggested putting all currently planned SLBM warheads (roughly 1,000) on eight subs to make up for the elimination of four of the boats. (Breaking Defense readers will remember what happened when OMB suggested something similar).

This doesn’t work. Two submarines on patrol cannot cover the same targets as the current four to five submarines on patrol, no matter how many extra warheads their missiles might carry. Two-thirds of the targets we now hold at risk would suddenly be in a sanctuary from which they could be used to attack the US and our allies.

This undermines our nuclear deterrent requirements. And it would increase pressure on our allies to either deploy their own nuclear weapons or make accommodations with our adversaries.

Some critics of the Navy budget proposals appear not to understand what the basis is of the Navy requirement for 12 submarines. Some have suggested that the strategy is one in which we would launch our submarine missiles quickly in a crisis–what some refer to as “prompt launch”.

This idea apparently stems from confusing a capability—much of our nuclear forces can be launched quickly in a crisis IF already placed on heightened alert. But that is not our strategy.

Submarines on patrol are there precisely so they DO NOT have to be launched promptly. The entire US nuclear deterrent strategy for many decades has been to have a secure second-strike retaliatory capability, especially in the submarine fleet. This eliminates any need to launch any of our nuclear weapons quickly in a crisis. This is possible because there is no current danger that the sub force could be found and destroyed before launching its missiles — even should a U.S. retaliatory launch be ordered by the President after an adversary’s first strike against the United States or its allies.

That was precisely the aim of nuclear modernization and simultaneous arms control proposals under previous administrations and which is a stated goal in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review.

Our strategic posture aims to lessen the temptation or incentives to launch our nuclear weapons quickly in a crisis. It is also designed to make our nuclear assets difficult targets so that an adversary is not tempted to strike us first.

The synergy between all three legs of the nuclear Triad (bombers, missiles and subs) thus makes it impossible for any adversary to strike all three legs simultaneously and thus the compulsion of an enemy to strike first in a conventional or nuclear crisis or conflict is virtually eliminated.

The 2010 START and 2002 Moscow strategic arms control treaties and the limiting of our land based missiles to one warhead each has helped considerably to move us toward that goal.

By not having to use such weapons early in a crisis, strategic stability is maintained and the chances that nuclear weapons would be used against the United States are significantly lessened.

What about the proposal to delay acquisition of a new strategic bomber? The new bomber is not just for nuclear purposes. Current law requires the new bomber to be nuclear capable only two to three years after its initial deployment as a conventional platform. And its nuclear related costs are just 1.5 percent of the total cost –less than $1 billion — for the new bomber force, hardly cause for alarm.

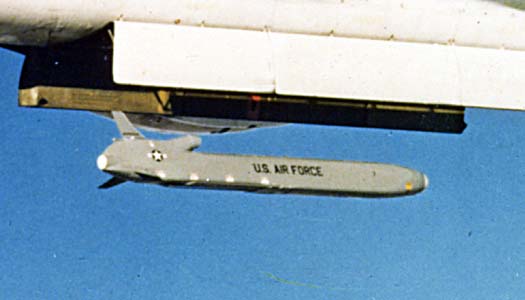

What about the idea of eliminating the new ALCM? That makes no sense either. Adding a cruise missile capability is needed to deal with enemy air defenses of increasing capability for both conventional and nuclear requirements.

Vietnam shot down over 1,700 US tactical airplanes and 17 B-52s and that was over 40 years ago. We only have 20 B-2 bombers that have both a needed penetrating capability today and a modern, effective ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) capability.

Given these limits, carrying out a conventional campaign such as Desert Storm that required hitting over 30,000 aim-points, could not be done in the future with the airplane fleet of today.

The penetrating capability of a new strategic aircraft is also critical to find mobile and re-locatable targets while the stand-off ALCM allows the targeting of an enemy’s time-urgent assets. It also compels the enemy air defenses to have to deal with a very large number of missile assets, as opposed to a smaller number of strategic aircraft.

As for the Minuteman land-based missiles, the Air Force is moving in the right direction. First, a recent Rand study recommended a modernized force and supported an option that turned out to be very similar to what the recent Air Force’s own Analysis of Alternatives (AOA) also concluded was the correct path forward.

Second, while it is true that Minutemen can be sustained for the immediate future, the missile technology needs to be modernized, including at some point the ground-based support equipment is approaching a lifetime of 50 years.

Third, the future force will not be mobile—as some seem to believe– as the recommended modernized force will remain in fixed silos as they are today — at a very significant lower cost.

Fourth, the costs of a modernized land based strategic deterrent force would be roughly $42 billion over 20 years, or about $2.2 billion a year compared to the $1.5 billion we are spending today. Thus, the notion that a future ICBM force will cost $200 billion, as some analysts have concluded, is not consistent with what the Air Force has chosen and is off by a factor of at least 400 percent. A new ICBM also will be dramatically lower in annual operations and maintenance costs.

Some critics have not only called for the elimination of key elements of our nuclear deterrent, they have also argued the current New Start Treaty warhead levels are in excess of what is needed.

Could the United States deploy fewer than the 1,550 to 1,800 strategic warheads we have today? Yes, but such a move would make no sense if deterrence could not also be maintained. Our deterrent requires a balance with potential adversaries and a force which is “second to none” as underscored by a 2014 essay by Henry Kissinger and Brent Scowcroft, both former Presidential national security advisers.

Some analysts have concluded that we could unilaterally reduce our total warheads to 1,000—including reserve, hedge and operational weapons, and still have 200 retaliatory weapons available.

Implicit in such a claim is that the deployed strategic nuclear force would have to be nearly all submarines carrying roughly 600 warheads aboard six to eight submarines.

Each of the 16 missiles planned for the Ohio Replacement Program would have to carry six warheads to have two submarines on patrol able to retaliate with 200 weapons.

Such a force would present an adversary with no more than six targets. That would significantly heighten strategic instability.

Others have claimed that 1,000 deployed weapons would be sufficient to meet our deterrent goals even should Russia not follow suit. They also assert the administration won’t unilaterally reduce to that number for political reasons; although deterrent requirements would allow it.

But there is no record of this administration testifying before Congress that unilaterally reducing to 1,000 total warheads — up to a one-third reduction from the current New Start level — can be done and meet current deterrent requirements.

But the implicit math is the same. Squeezing current bomber weapons (400 to 700), ICBM warheads (400) and the current Trident missiles (around 1,000) into a total deployed ceiling of 1,000 warheads requires killing upwards of two legs of the triad.

Or conversely, it would significantly weaken each leg of the triad to where the deterrent capability of the US nuclear force will no longer be able to meet its required goals.

Russia does not plan to reduce its strategic forces to such levels. In fact, it is trying to modernize its strategic forces at a rate not even seen during the height of the Cold War. And no US administration has made any progress is controlling the level of Russian tactical nuclear weapons deployments, which further complicates any reductions to such warhead levels.

As for China, it rejects outright any arms control restrictions on its nuclear forces even as it keeps their capability and numbers secret. Finally, we should be cognizant of the reported request by the senior military leaders of China to do combined military exercises with the Russians that would “jointly” target the United States with nuclear weapons.

Furthermore given China’s growing nuclear arsenal and its plans for global hegemony (backed up by nuclear weapons and other asymmetric military capabilities as revealed in a new book by Mike Pillsbury, The Hundred Year Marathon) a significantly smaller US deployed strategic nuclear force could easily be outnumbered by a combined Russian and Chinese strategic arsenal by three to one or more.

The nuclear deterrent has prevented nuclear weapons from having been used, especially by the two largest nuclear armed adversaries, for some 70 years. This is an extraordinary record.

Cutting the very backbone of our nuclear security is not the way forward to a safer world or safer America.

Peter Huessy, president of the consulting firm GeoStrategic Analysts, also organizes the Air Force Association’s well-known breakfast series on Congress and space issues.

In a ‘world first,’ DARPA project demonstrates AI dogfighting in real jet

“The potential for machine learning in aviation, whether military or civil, is enormous,” said Air Force Col. James Valpiani. “And these fundamental questions of how do we do it, how do we do it safely, how do we train them, are the questions that we are trying to get after.”