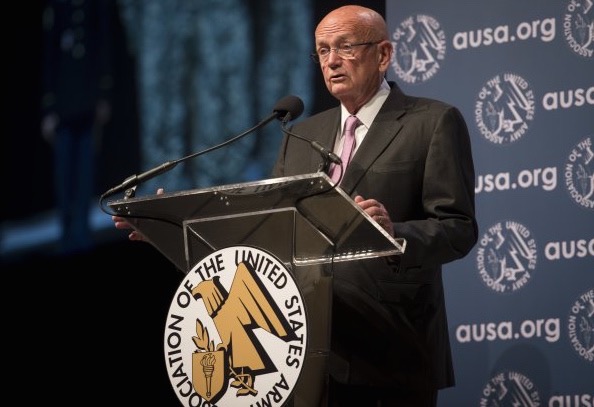

Gen. Gordon Sullivan

The Army has gotten smaller every year since 2011, while the threats have gotten greater. Simply put, America’s Army – our nation’s foundational force since 1775 – is asked to face a dangerous and uncertain world with reduced and uncertain resources. It is confronted by turmoil abroad and hindered at home by politicians unable or unwilling to agree on core American needs.

The lone bit of budgetary stability in 2015 was a two-year reprieve from having sequestration hanging over our military. This is hardly a beaming beacon of success for a government that gives more attention to petty squabbles than to our nation’s security.

Even as national security and the threat of terrorism have risen as the top concerns of the American public, some of our elected and appointed officials have developed a mindset that avoids reality. We are going to crush terrorism and all the evil in the world, apparently with the snap of fingers by a new commander in chief, rather than by rebuilding a battle-worn and underfunded military so it is capable and ready to face today’s security environment.

If the Army were a major sports franchise, 2016 would be considered a rebuilding year. But threats to our homeland, our interests and our allies are not going to wait while the Army recovers from more than a decade of war and the budgetary wounds inflicted on it by a dysfunctional political system. The real world isn’t going to wait until after the presidential election for decisions on national security priorities and how much to spend on our defense.

America’s Army is getting smaller, with the combined active, Army Guard and Army Reserve force expected to drop by 27,000 this year to a little more than 1 million soldiers. Only 30 percent of brigade combat teams are ready to fight, a deficit that won’t be fixed until 2020. The Army’s budget is flat, and so is morale in the ranks.

The undersized Army is hidden, in part, by reliance on special operations forces to carry out global missions that previously were accomplished by regular soldiers. Make no mistake: Elite Army troops—now numbering about 26,000—provide combatant commanders with crucial capabilities that proved their value in Iraq and Afghanistan and are proving it again against Islamic State militants and other threats. However, the 1,750 Special Operations soldiers in Afghanistan are not the same as having a 4,500-member brigade combat team on the ground. The 200 troops in Iraq involved in what the Pentagon now calls a “specialized expeditionary targeting force” do not eliminate the need for the Army to be prepared to redeploy a sizable force if that is what is required to blunt Islamic State advances.

Bullies of all kinds prey on the weak and timid. I wouldn’t label our under-resourced Army as weak, as it remains the world’s premier land force even now, but we are showing timidity by responding with tough talk but little action to situations where quick, decisive use of force is needed. Our inaction and hesitation feed an emerging view that the US is unlikely to do anything and if we act, will do only the minimum in terms of showing the flag without going all-in for the victory.

Tight budgets, the continued drawdown of force structure in the face of growing risks, and the inability of our political class to stop quibbling and agree on a common national security posture are undermining morale of our troops, our civilian workforce, and their families. That may be the greatest problem of all, because our Army and our nation’s security depend on the selfless service of our soldiers.

Gordon R. Sullivan, former Army Chief of Staff, is president and CEO of the Association of the US Army.

Out of INF, Army deploys Typhon weapon to the Philippines

“This is a significant step in our partnership with the Philippines, our oldest treaty ally in the region,” said Brig. Gen. Bernard Harrington, commanding general of the 1st MDTF.