Defense Secretary Ash Carter talks to Strategic Capabilities Office director William Roper at Submarine Base New London.

As Defense Secretary Ashton Carter toured naval sites in New England this week, one aide was almost always standing at his side: William Roper, head of the quietly important Strategic Capabilities Office.

On the flight home to Andrews Air Force Base, the often press-shy secretary surprised reporters — and, it seems, his staff — with an impromptu appearance in the back of the plane to sing Roper’s praises on the record.

“He’s important…not only for what he does but for the example that he represents: young technical talent determined to do things fast but effective,” Carter said. “I built the Strategic Capabilities Office around him…an entire office, which he at a very young age is the head of, which is one of the most innovative parts of OSD (the Office of the Secretary of Defense).” SCO’s mission is to accelerate selected innovations that can make a big difference in a short time.

While many SCO projects are highly classified, one public success story is upgrading the software on the Navy’s SM-6 Standard Missile, originally designed for anti-aircraft and missile defense, so it can strike enemy ships as well. As a result, the number of missiles the Navy’s buying with anti-ship capabilities over the next five years increased from 60 to over 600.

“I can’t run on enough about Will,” the secretary said as aides gently corralled him back to his seat for landing. “Good people deserve credit.” After all, people are policy.

Among the secretary’s many stops in New England, from Yale University to the Naval War College, Roper was most visibly at Carter’s side during our visit to one of the Navy’s newest nuclear submarines, the USS New Mexico, and to the labs at the Naval Undersea Warfare Center, where a visibly delighted Carter got to direct an unmanned scout boat and to study seals’ whiskers as a model for military sensors. At such places, Cater said, “I want him to see the themes I’m sounding with these folks…and make them see him as representative of what we all need to do.”

What are those themes? “One is the centrality of agility,” said Carter, who spearheaded efforts to quickly find and field roadside-bomb-resistant MRAP vehicles in Iraq and has fought hard to make the Pentagon procurement system faster and more responsive — an effort Roper is now at the forefront of. The second, Carter continued, is “the importance of reaching down and bringing up bright people and giving them power and authority.” That’s where Roper comes in.

The New England trip, with Roper often at Carter’s side, highlighted three of the secretary’s priorities:

- The need to innovate. “This facility is doing what we all need to be doing everywhere in the department, which is speeding up the pace at which ideas get into the fleet,” he said at the Navy Undersea Warfare Center. “Many of the things that they’re doing here, even if fielded in very small numbers — not in tens or hundreds or big industrial builds, but in small numbers — can make a decisive difference.”

- The need to preserve and extend our undersea advantage. Submarines and sub-launched drones will be networked to the larger force. “It used to be that undersea warfare was a domain unto itself,” Carter said at NUWC. “Now, the Navy is connecting it to….the surface Navy, and to the land and air forces, which is very important, creating an integrated domain to include, by the way, the sea bed.”

- The need to attract, retain, and promote younger technical talent to leaven an experienced but aging workforce. “Seeing those two generations working together is inspiring,” Carter said at NUWC. “They have the best of both the brand new recruits (and) people who have been here for years and have very great technical depth.”

Secretary Carter and SCO director Roper (far left) in the control room for an unmanned boat at the Naval Undersea Warfare Center

Scientists At Work And Play

The Navy Undersea Warfare Center was the stop on this trip where Secretary Carter clearly had the most fun. On arrival, he took the controls of an unmanned boat out in Narragansett Bay. Four similar NUWC robo-boats are currently hunting mines in the Persian Gulf, but this one is a testbed for sensors and collision-avoidance systems, including a hailing device being developed jointly with the Coast Guard. As a testbed, it had a human being aboard, not as an operator but as a safety officer — just in case.

Carter snarked when he noticed the man’s safety gear: “It doesn’t really instill confidence in the Secretary of Defense that the guy has a survival suit on.” Later, once Carter had input the waypoints — with Roper watching — and set the boat on its way, he emerged from the control room chortling, “All right, you’d better tell this guy to hold on for dear life.”

“If I did it right, he’ll clear that jetty,” Carter told his entourage while he watched the speeding boat through binoculars. “If I didn’t” — long pause — “there’ll be lessons learned.”

(Unsurprisingly, there was no crash).

Carter also enthused over unmanned underwater vehicles and a miniature scout drone — “I like that little guy” — that can be launched from submarines. He engaged eagerly with young NUWC staff who’d done extracurricular research projects on everything from the aforementioned seal whiskers, which are more sensitive than any Navy sensor, to growing hydroponic berries on subs, hacking underwater drones and scattering swarms of disposable floating sub-detectors. In fact, he walked away with the 3D-printed prototype sensor, prompting nervous looks between the two young scientists.

Carter’s enthusiasm is rooted in being a scientist himself. The defense secretary worked on quarks at the famous Fermilab before he was tapped to study MX missile deployment in late 1970s. It’s likely that Carter sees Roper — a fellow physicist and Rhodes Scholar — as a younger version of himself.

“It was about four or five years ago that I was undersecretary and Will Roper was working at the Missile Defense Agency,” Carter recounted to reporters on his plane. “I didn’t know him, but he came in and gave a spectacularly smart briefing…..You know how you can spot someone who is really sharp?”

“I was wrestling in that time with this problem of agility, particularly in connection with the wars (in Iraq and Afghanistan) but also in connection with China, and China wasn’t getting the attention (it deserved), but it had my attention,” Carter continued. “So I plucked Will out of the Missile Defense Agency, put him in the Pentagon, and had him report to me.”

“I was trying to take the things that we had learned in the war, like with MRAPs, and apply them to longer term challenges, where I didn’t want to be on the 10 or 15 year program schedule,” Carter explained. “The answer that ‘we’ve got a program that will do that in 2021’ or ‘we’ll start something that will take 10 years’ is completely ridiculous when there are people dying.”

Roper “started to work on these problems and I brought him along when I’d met with the chiefs” — that is, the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “He proved himself so well, not just to me,” Carter said, “but especially to the Chief of Staff of the Air Force and the Chief of Naval Operations at that time.”

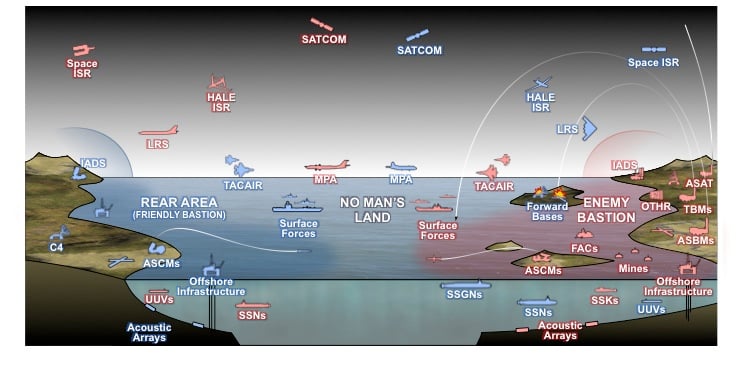

Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments graphic

Submarines vs. China

It’s the Air Force and Navy that were then leading the Pentagon’s reorientation from counterinsurgency in the Islamic world to long-range Air-Sea Battle. The new threat derived from the proliferation of technologies once a US monopoly: precision-guided missiles, the sensors to target them, and the communications to transmit that targeting data. With such technologies organized in Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) systems, China and for that matter Russia could increasingly endanger US warships and aircraft. What surface and air forces weren’t shot down or sunk might be blinded by jamming and hacking.

The hardest US forces for enemies to find are submarines. Being underwater, however, also makes it harder for submarines to communicate with the rest of the force. Modern submarines can do much more than fire torpedoes: They can collect intelligence on coastal regions, strike targets deep inland with Tomahawk missiles, or even deploy Navy SEALs. But if they’re to be the cutting edge of the entire American military, they need to be better connected to it — and that’s a formidable technological challenge.

“You saw the variety of unmanned vehicles — both sub-surface, on the surface, and above the surface — but it’s also connecting those things together,” Carter said at the Navy Undersea Warfare Center, “connecting the undersea domain, in which we have this tremendous superiority, to the surface and air domains, where the challenges are in some ways greater.”

It’s Roper’s Strategic Capabilities Office that will be on the cutting edge of solving these problems. Their mandate is not to create Manhattan Projects. The military has plenty of people doing big, costly long-term programs. SCO’s mission is to find fast, effective and affordable ways to make existing weapons do new things, for example by inserting new technologies as upgrades or by connecting previously independent systems.

“Roper has direct support from the Secretary and DepSec (Deputy Secretary Robert Work); he has his own funding, a well defined mission, a small team, a focus on short term objectives; and he’s working to optimize existing technologies in combination with new CONOPs (concepts of operation),” said Ben Fitzgerald, director of the technology program at the Center for a New American Security. “That means they can move quickly, address immediate priority issues, and don’t get bogged down with project overruns while waiting on engineering miracles.”

Lockheed wins competition to build next-gen interceptor

The Missile Defense Agency recently accelerated plans to pick a winning vendor, a decision previously planned for next year.