M1 tank at the National Training Center in 2015.

ARLINGTON: The US Army isn’t counting on airpower in the next war. Without that cover, there won’t be supply drops, recon drones or medevac helicopters picking up your casualties — and you will have casualties.

“Land-based forces now are going to have to penetrate denied areas to facilitate air and naval forces. This is the exact opposite of what we have done for the last 70 years, where air and naval forces have enabled ground forces,” Gen. Mark Milley, the Army Chief of Staff, said last month.

Gen. Mark Milley

Milley’s referring to a modern American way of war that emerged at least as early as 1944, with the landings at Normandy in France and on Tinian in the Pacific. The US first secured control of sea and sky, then bombarded enemy ground forces, and only then landed ground troops, followed by waves of reinforcements and supplies. But every step in this process is now threatened by the proliferation of long-range precision missiles, along with the sensors to target them and the networks to command them — a combination known as Anti-Access/Area Denial.

So as bad as Iraq and Afghanistan have been, a war against a well-armed adversary like Russia, China, or their customers would be worse — worse in ways that overturn longstanding assumptions about how America fights. Above all, long-range missiles targeting US aircraft, aircraft carriers, and airbases may disrupt the air support on which US ground troops have depended since the Second World War. Hacking and jamming will disrupt communications and blind sensors. Anti-tank missiles, artillery rockets, and roadside bombs will disrupt supply convoys and devastate static bases.

“On the future battlefield, if you stay in one place longer than two or three hours, you will be dead,” Milley told the Association of the US Army. “Being surrounded will become the norm.”

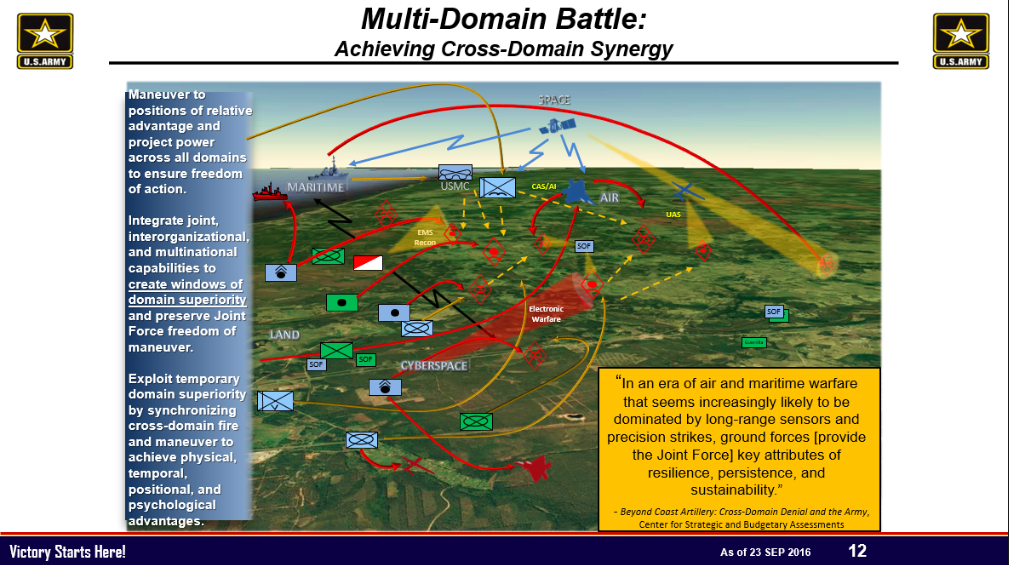

That grim picture is just the starting point for the evolving battle concept known as Multi-Domain Battle. Rather than count on America’s accustomed advantages — on-call air support, regular resupply, constant communications with higher headquarters — soldiers must take the initiative to seize fleeting moments of temporary advantage. US soldiers must learn to operate in small units with minimal support and to force open narrow windows of opportunity with whatever they have at hand.

That grim picture is just the starting point for the evolving battle concept known as Multi-Domain Battle. Rather than count on America’s accustomed advantages — on-call air support, regular resupply, constant communications with higher headquarters — soldiers must take the initiative to seize fleeting moments of temporary advantage. US soldiers must learn to operate in small units with minimal support and to force open narrow windows of opportunity with whatever they have at hand.

Those future units’ assets may include new armored vehicles, long-range missiles, cyber and electronic warfare gear, allowing ground units to take on functions once outsourced to the Air Force and Navy. Indeed, the idea behind the jargon term Multi-Domain is that Army forces will not only become more self-sufficient, but they’ll be able to extend their reach beyond the land to support operations on the sea and in the air.

There wasn’t much of a role for ground troops in the first attempts to counter Anti-Access/Area Denial, a concept called Air-Sea Battle. The initial solution was “rollback”: stand off at the longest possible range, where most of the enemy weapons can’t hit you, and gradually wear the defenders down with your own long-range missiles. You take out their longest-range system, move a little closer, take out their second-longest-range system, repeat.

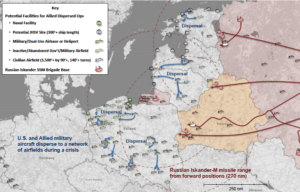

Defense against a notional Russian missile barrage. (CSBA graphic)

The problem is this outside-in approach is painfully slow. For allies trapped inside the enemy’s A2/AD zone — Russia’s covers the Baltic States and much of Poland — it means the US cavalry isn’t coming any time soon. For adversaries smart enough to seize what they want in their initial surprise attack — as Russia did in Crimea — it means you can probably hunker down and wait the Americans out. So there’s a growing sentiment in all the US services that they should push harder and faster.

“To some, A2/AD is a code-word, suggesting an impenetrable ‘keep-out zone’ that forces can enter only at extreme peril to themselves,” wrote Adm. John Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations. “The term ‘denial, as in anti-access/area denial’ is too often taken as a fait accompli, when it is, more accurately, an aspiration.”

So instead of treating A2/AD as a death zone that can only be dealt with from a distance, the evolving approach treats A2/AD as a complex system with inevitable weak points for US forces to penetrate. Like water through a damaged dam, the first attacking elements seep through the cracks — long-range strikes, Special Operations raids, cyber attacks — and force them open a little wider, allowing larger forces to flow in and force the openings wider yet, until the whole structure shatters from the inside out.

German stosstruppen (storm troopers) on the attack in World War I.

This is a new application of an old idea. Between the World Wars, military theorist B.H. Liddell Hart called this “the expanding torrent.” It was invented by Germany’s elite stormtroopers in World War I: Instead of advancing steadily into machinegun fire in traditional, easily targeted battle lines, the stosstruppen formed small teams that advanced independently, taking cover wherever they could, penetrating weak points and bypassing strong points — even if that meant leaving enemy forces between the stormtroopers and the rest of the German army. (Hence the term “infiltration tactics.”)

The German blitzkrieg of World War II mechanized stormtroop tactics with tanks, trucks, and planes that let it operate much faster over a much larger scale, all bound together with radios. Multi-Domain Battle and the related Marine Corps Operating Concept basically scale up blitzkrieg, with units dispersing over even wider areas. As weapons become longer-ranged, more lethal, and more precise, ground units must move further to close with the enemy and disperse more widely to avoid presenting easy targets.

“With sensors everywhere the probability of being seen is very high, and as always, if you can be seen, you will be hit, and you will be hit fast — with precision or dumb munitions — but either way you will be dead,” Milley said. “So that means just to survive our formations, whatever the wire diagram looks like, will likely have to be small, they’ll have to move constantly, they will have to aggregate and disaggregate rapidly. They’ll have to employ every known technique of cover and concealment.”

The problem with this is it’s risky. Instead of keeping your forces together in a mutually supporting battle line, you empower junior leaders to plunge ahead when they think they see an opportunity. If they call it wrong, or if the fortunes of war just switch too swiftly, units end up isolated and cut off. For Multi-Domain Battle in particular, a doctrine specifically built on exploiting fleeting advantages, it’s all too possible that a US airstrike, artillery barrage, cyber attack, or burst of jamming might paralyze the enemy long enough for ground troops to advance — only for the enemy to recover and slam the door shut behind them. That’s what Gen. Milley meant when he said “being surrounded will become the norm.”

Gen. David Perkins

“That’s one of the big things we’re looking at,” said Gen. David Perkins, chief of the Army’s Training & Doctrine Command (TRADOC), which authored the Multi-Domain Battle concept. “You more than likely could have a very high level of dispersion of forces, (some) of which get to a position of relative advantage when the window of domain superiority is open, and then it closed,” Perkins told a recent Association of the US Army breakfast. “So now what do you do?”

“A couple of things have become the long pole in the tent,” Perkins continued: protection and sustainment. How you protect an isolated unit, without friendly forces massed nearby to support it? How do you keep an isolated force supplied and sustained, when the supply lines must travel through no man’s land?

“You take the maneuver concept, which dispersed forces over large areas,” Perkins elaborated to reporters. “Now I’ve got to come up with a new sustainment concept, which is probably not the one I grew up with, which is the first sergeant gets in his jeep and drives back, gets a trailer, fills it full of scrambled eggs, and drives it out to everybody.”

Lavish logistics has been a US strength since World War II, but Iraq and Afghanistan showed how bloody it can be to drive supply trucks through territory you don’t fully control. The Army’s looking hard at expendable unmanned supply vehicles — both self-driving trucks and cargo drones like K-MAX — to reduce the number of soldiers exposed in convoys. It’s also looking at reducing the amount of supplies that frontline units require, both by having them 3D-print spare parts on site and by issuing them lighter, less fuel-hungry combat vehicles. Evacuating casualties to the rear will be as hard as pushing supplies forward, so frontline units will also need much more on-site medical care.

While we can find new ways to deliver supplies through danger zone “like Amazon on steroids,” said Perkins, “we (also) have to reduce our sustainment demand on the system, because they may very well have to operate some place for extended periods of time and we won’t have continuous lines of communication” to send supplies.

Raytheon Quick Kill Active Protection System

But reducing the demand for supplies means, above all else, reducing fuel consumption. That requires reduced weight — which means smaller weapons, less ammo and — especially — less armor. M1 Abrams tanks are probably the best protected vehicles in the world, but they get about three gallons to the mile, and one unit had to shut down temporarily in downtown Baghdad in 2003 until fuel trucks pushed through to them, with heavy casualties. The Army is looking intently at lightweight electronic jammers to send incoming weapons off-target and mini-missiles to shoot them down. The Russians and Israelis have used such Active Protection Systems to great effect — but they layer it on top of heavy tank armor, not replacing it.

So whichever approach you take, there’s risk. Lighter forces risk being too fragile to take a hit; heavy forces risk running out of gas. Clever tactics and new technology can reduce the danger, but they’ll never take it away. As Milley put it last month, “future high-end war between nation-states and great powers…will be highly lethal, very highly lethal, unlike anything our Army has experienced since at least World War II.”

Jordan walks careful line after shooting down Iranian strikes headed to Israel

Amid Iranian criticisim, “Jordanian leaders have been very clear to portray their action as defensive and in protection of their own sovereignty rather than any act in support of Israel, and this is sincere,” an analyst told Breaking Defense.