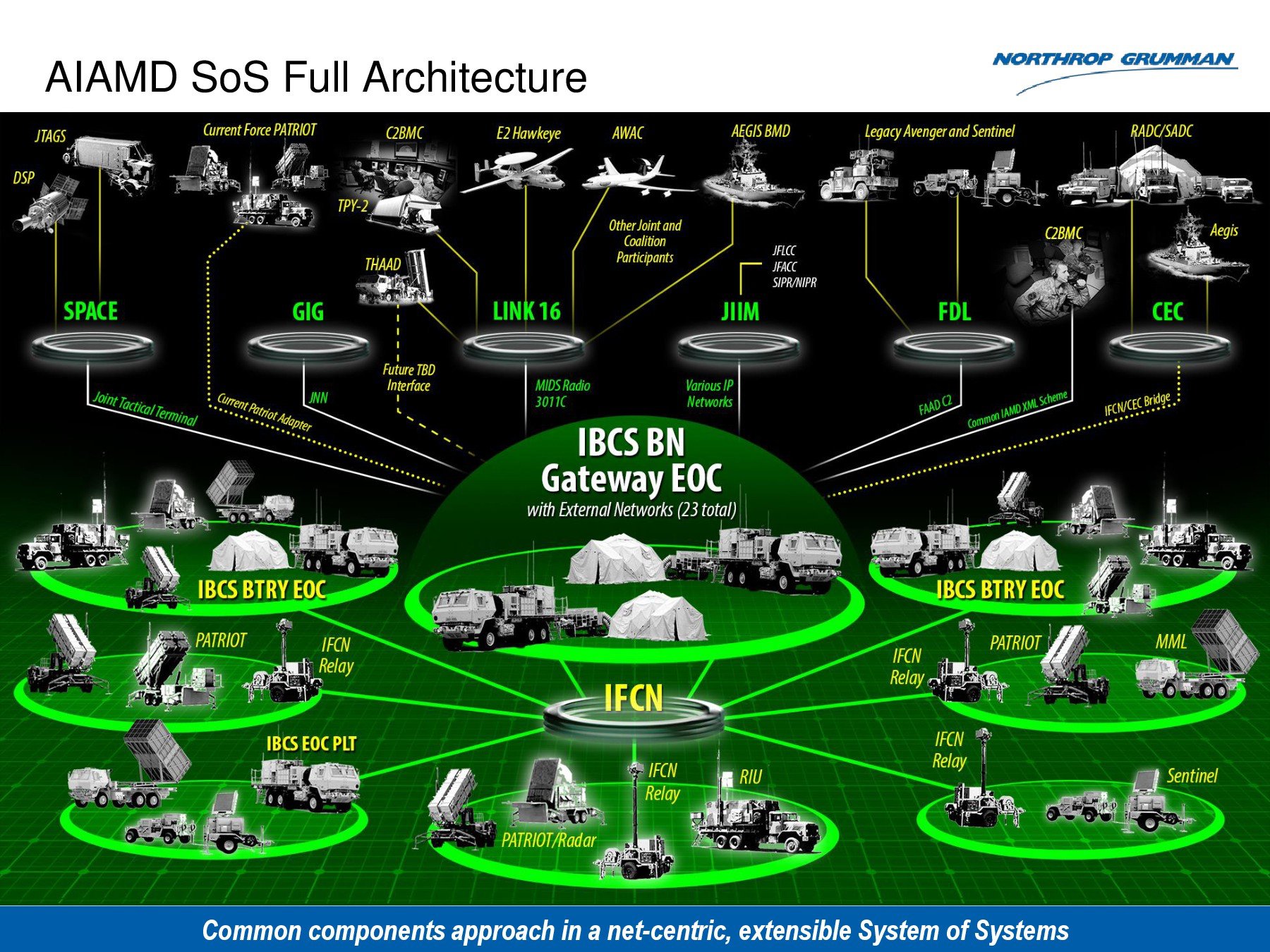

A simplified (yes, really) overview of IBCS command-and-control network

America’s military has operated far too long without a truly integrated air and missile defense system and the Army’s Integrated Air and Missile Defense Battle Command System (IBCS) is the best answer we’ve got. Congress needs to support the Army’s budget request for IBCS and AMD funding. For its part, the Army needs to re-evaluate its management approach.

IBCS will take us from stove-piped, stand-alone weapon systems to the integrated air and missile defense we require. IBCS’ open architecture and “any sensor-best shooter” construct is the objective our commanders must have to deal with the threats of today and tomorrow.

As Adm. Harry Harris, Commander of the U.S. Pacific Command, recently told Breaking Defense, “I want them to be able to deliver a missile on target, and I want them to be able to do it interchangeably. In other words, I want the Navy to be able to do the sensing and the Army to do the shooting, or the Army to do the sensing and the Navy to do the shooting.”

IBCS is only seven years into development and it has accomplished much. The Army needs to re-evaluate its management approach and ensure it is disciplined and establishes a block concept to manage emerging requirements. It needs to lock-in configurations prior to test and provide well-trained and experienced crews to execute the test and analyzes test results to determine root causes for shortcomings and to ensure they are scored and binned accurately. Finally, the Army needs to ensure its requirements are operationally based, realistic, and technologically feasible.

A disciplined approach sets the stage for sustained program success. Let’s discipline ourselves, focus on the next test, measure our advancement towards making improvements and fulfilling the objective of giving the warfighter a capability that will better protect our troops and allies abroad.’

The good news is IBCS’ three live fire tests and demonstrations have been resounding successes. It has demonstrated the ability to use any sensor to enable a shooter “without eyes on the target” to intercept at greater range. It has integrated Aegis data and other joint sensor data to improve combat identification, decision time, and defense effectiveness. IBCS will redefine air and missile defense weapon systems, how we employ them, and how we fight them – and give us greater capability, over greater battle space, than any of today’s weapons can.

But staying the course is hard when an early report finds fault. Leaders know that first reports are often inaccurate and, if you have a solid plan, the right course of action is to execute and adjust it after details become known and the situation is clearer.

The recent critical Office of the Director for Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E) IBCS test report is but a single report, on a single test event. But, with further examination and thought, one might ask, “How were things evaluated, scored, and binned? What were the operational under-pinning of the requirements tested – not merely the metrics, but the operational rationale that justifies the metric? Are they technologically feasible today?”

The Army has accepted great risk in air and missile defense, as evidenced by its Short Range Air Defense (SHORAD) force – its force structure was a bill payer for modularity and investment in SHORAD capability has been minimal.

The air and missile defense mission is and always has been one of the most challenging. Army systems have walked this trail before – who can forget THAAD’s lackluster early years? Zero for five before there was an intercept. We didn’t pull stakes on that program in 1999, but we did re-evaluate it and re-organize our approach, which led to success. Where would we be today if we’d cancelled that program?

The FAAD Ground Based Sensor was another program with a rocky start due to operational requirements plated in “un-attain-ium”. A single vendor responded to its request for proposal (RFP) and that sensor went through a horrendous test, where it performed poorly against threshold requirements of 95 percent and objective requirements of 99 percent.

A re-evaluation of the requirements and the application of operational logic, generated an RFP that seven vendors responded to and in a second test, the original vendor’s sensor decisively out performed all others. That sensor is today’s Sentinel radar.

The Army’s recent track record for program termination is also not reassuring, as it has abandoned programs which offered great promise and phenomenal operational capability, like JLENS or low risk, like SLAMRAAM. We don’t need to assess changing horses at this time, but we do need to evaluate how the program is being managed. With the Army as the IBCS Lead System Integrator, the Army owns it entirely. It’s not an easy job, especially for a new, novel technology like IBCS.

Francis Mahon is a retired Army major general who served as director for test at the Missile Defense Agency and as former commander of an Army Air and Missile Defense Command. He is not employed by or working with any company related to IBCS.

Move over FARA: General Atomics pitching new Gray Eagle version for armed scout mission

General Atomics will also showcase its Mojave demonstrator for the first time during the Army Aviation Association of America conference in Denver, a company spokesman said.