Does not include foreign personnel killed aboard US aircraft.

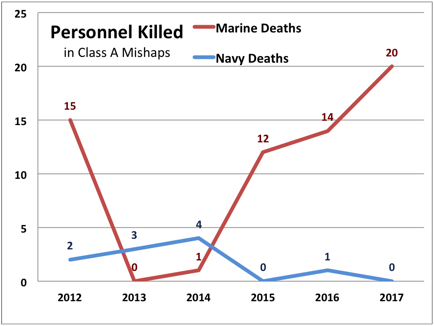

WASHINGTON: If you know a young person who dreams of flying for their country over land and sea, tell them they’re a lot safer in the Navy than in the Marines. The MV-22 tilt-rotor that crashed in August, killing three, and the KC-130T transport that crashed in July, killing 16, are just the tip of a very ugly iceberg. According to data obtained by Breaking Defense, aircraft accidents have killed 62 Marines in the last six years, compared to just 10 personnel from the much larger Navy.

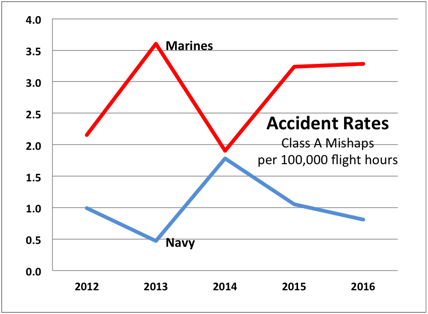

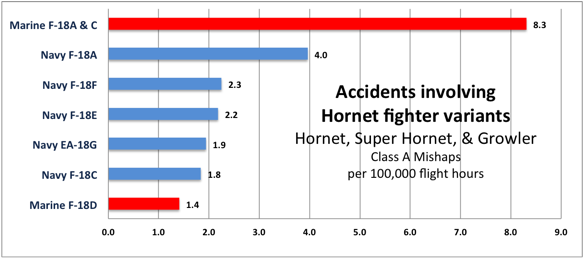

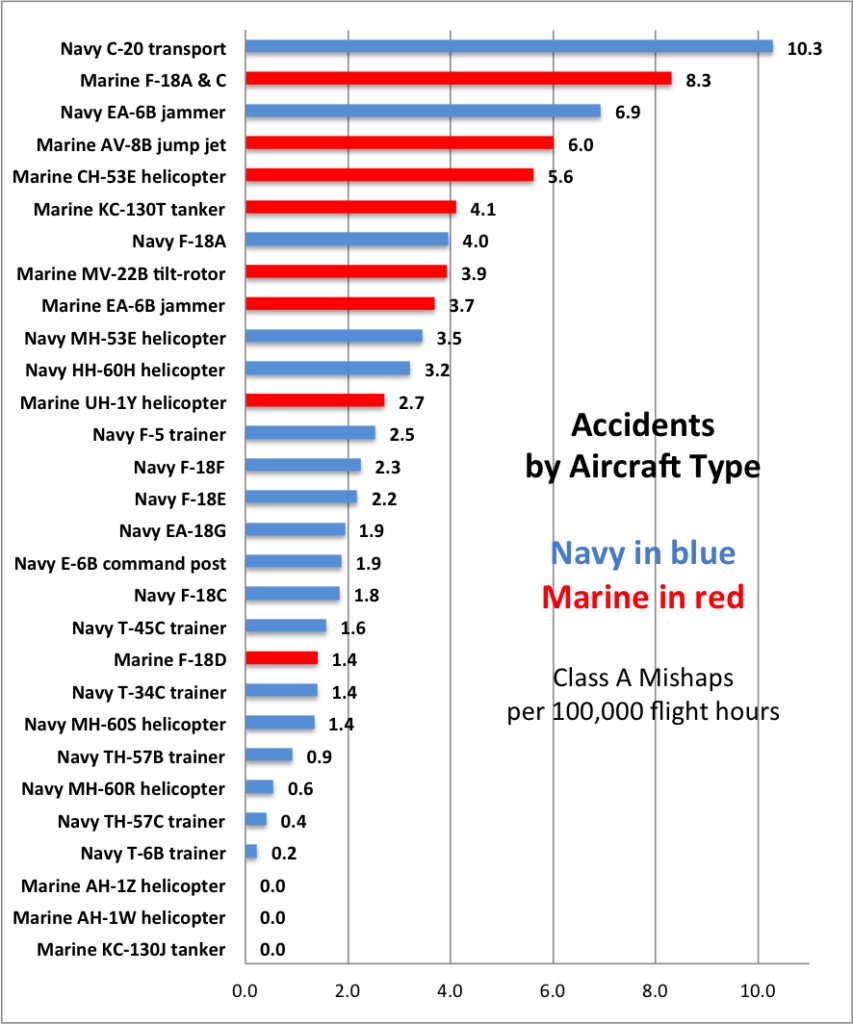

The other metrics aren’t much better. Marine Corps aircraft suffer more so-called Class A Mishaps, involving loss of life or $1 million in damage, at consistently and significantly higher rates per 100,000 hours flown. (Non-fatal accidents are up, as well). If you look at the services’ mainstay combat aircraft, the F-18 Hornet fighter family, which both services operate and are struggling with, the Marines’ single-seater F-18As and Cs are twice as dangerous as the comparable Navy models.

The other metrics aren’t much better. Marine Corps aircraft suffer more so-called Class A Mishaps, involving loss of life or $1 million in damage, at consistently and significantly higher rates per 100,000 hours flown. (Non-fatal accidents are up, as well). If you look at the services’ mainstay combat aircraft, the F-18 Hornet fighter family, which both services operate and are struggling with, the Marines’ single-seater F-18As and Cs are twice as dangerous as the comparable Navy models.

What’s going on? Breaking Defense requested this data from the Navy and Marine Corps after this summer’s deadly accidents prompted Marine Commandant Robert Neller to order rolling stand-downs across all the service’s aviation units. The chairmen of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees, Rep. Mac Thornberry and Sen. John McCain, said the aviation accidents – and the two deadly collisions at sea that killed 17 sailors – were symptoms of a wider readiness crisis, in which years of insufficient and inconsistent funding have forced dangerous cutbacks to training and maintenance. There’s truth to that story, but it’s not the whole story.

First, it’s essential to understand that mishap rates may look precise and unambiguous, but they reflect a messy reality. Even when no enemy is involved, military operations are inherently risky, as is training for those operations. As Clausewitz wrote 200 years ago, chance is a major factor, and thus both accident rates and death rolls can vary dramatically from year to year. Particularly for a small fleet of aircraft that don’t fly many hours, a single bad accident can cause statistics to spike. For example, the KC-130T that crashed this summer was the only one to suffer a Class A mishap in five years, but it single-handledly pushed the type’s mishap rate from zero to 4.1.

First, it’s essential to understand that mishap rates may look precise and unambiguous, but they reflect a messy reality. Even when no enemy is involved, military operations are inherently risky, as is training for those operations. As Clausewitz wrote 200 years ago, chance is a major factor, and thus both accident rates and death rolls can vary dramatically from year to year. Particularly for a small fleet of aircraft that don’t fly many hours, a single bad accident can cause statistics to spike. For example, the KC-130T that crashed this summer was the only one to suffer a Class A mishap in five years, but it single-handledly pushed the type’s mishap rate from zero to 4.1.

All that said, however, something appears to be happening here that is more than just chance.

KC-130 landing.

One systemic difference between the Marine Corps and the Navy is that most Marines are ground troops, which means a lot of Marine aircraft are troop carriers. That can have a dramatic impact on death rates. If a single-seat fighter jet goes down, only a single pilot goes down with it, and he or she has an ejection seat to get out. If a fully loaded transport crashes, there can be 20 people or more aboard, none of them with the option to eject.

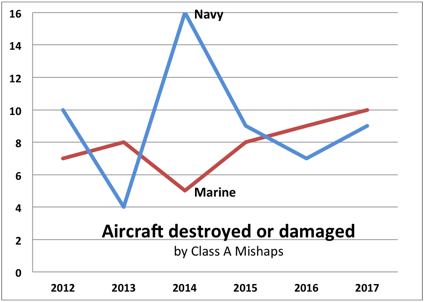

So even though the Marines lost six times more people over the last six years of accidents, they actually lost fewer aircraft. Some 47 Marine aircraft were destroyed or damaged in Class A mishaps, compared to 55 Navy aircraft (16 of them in a single annus horribilis, 2014, which was incidentally the year after sequestration cuts and, ironically, the Marines’ best year). But none of those Navy aircraft went down with a lot of passengers aboard.

Even if we set aside the tragic death toll, however, the Marines are losing aircraft at a disturbingly high rate. Yes, 47 Marine planes and helicopters destroyed or damaged since 2012 is smaller than 55 Navy aircraft – but not by much, and the Marine Corps is much smaller than the Navy. If a smaller group is having almost as many accidents as a larger one, the smaller one is having accidents at a much higher rate.

MV-22 Osprey tilt-rotor

And that’s exactly what we find. The Marine Corps’ rate of Class A mishaps per 100,000 flying hours varies a lot from year to year, as does the Navy’s. But in the very best year for the Marines, their rate is still 10 percent higher than the Navy’s. In most years, it varies between 100 and 300 percent higher. In the worst year, it’s 670 percent higher.

Part of the reason is that the Marines operate a lot of older aircraft. If you look at individual aircraft types, the highest rate of mishaps belongs to the Navy C-20s, basically Gulfstream business jets converted to military transports in the 1980s and 1990s: It’s a relatively old fleet, and it’s also tiny – just six planes – so a single mishap in 2014 has an outsize effect. If you look at the next highest aircraft, three of them are aging Marine Corps platforms:

- early-model F-18 Hornets that the Marines decided not to replace, while the Navy phased out its oldest F-18s in favor of new Super Hornets;

- the AV-8 Harrier jump jet, whose vertical takeoffs and landings made it risky to fly even when new;

- the CH-53E helicopter, which is being rebuilt and upgraded into the K-model;

- and the KC-130T transport, a small fleet where this summer’s crash has a huge effect on the statistics.

The remaining plane in this high-risk category is the Navy’s geriatric EA-6B Prowler; the Marines’ remaining Prowlers actually do much better, for some reason, possibly pure luck.

Interestingly, the mishap rate for the Marines’ prized MV-22 Osprey is also fairly high. (It’s the 8th highest on the combined Navy-Marine list of 29 aircraft types). That’s a relatively young aircraft, but its unique tilt-rotor mechanism makes it especially complex and has contributed to at least some accidents.

The age factor is probably the reason the Marines’ Hornet fighters are doing so much worse than their Navy equivalents. First of all, the Navy has a lot of the newer Super Hornet models, the F-18Es and Fs, as well as the radar-jamming variant, the EA-18G Growler; the Marines have none. Both services operate the original “Legacy Hornets,” the single-seater F-18As and Cs: The Marine A and Cs suffer mishaps at more than double the rate of their Navy counterparts. Surprisingly, the Marines’ two-seater F-18Ds are safer than any Navy Hornets, perhaps because they’re chiefly used for training with an experienced instructor in the back to oversee the new pilot.

A Navy F-18C Hornet.

Rather than join the Navy in buying Super Hornets, the Marines made a decision 20 years ago to keep their legacy Hornet fleet and wait for the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. After many delays, the first squadron of F-35Bs was declared war-ready in 2015, and it combines the strike fighter capabilities of the Hornet with the jump-jet, small-deck operations of the Harrier. But in the meantime the Hornets and Harriers have aged badly, in part due to design shortcuts taken in the 1970s.

To a great degree, today’s young Marines may be suffering because of decisions made before they were born. Given the magnitude of the task at hand, it may take another generation to solve the problem.

In a ‘world first,’ DARPA project demonstrates AI dogfighting in real jet

“The potential for machine learning in aviation, whether military or civil, is enormous,” said Air Force Col. James Valpiani. “And these fundamental questions of how do we do it, how do we do it safely, how do we train them, are the questions that we are trying to get after.”