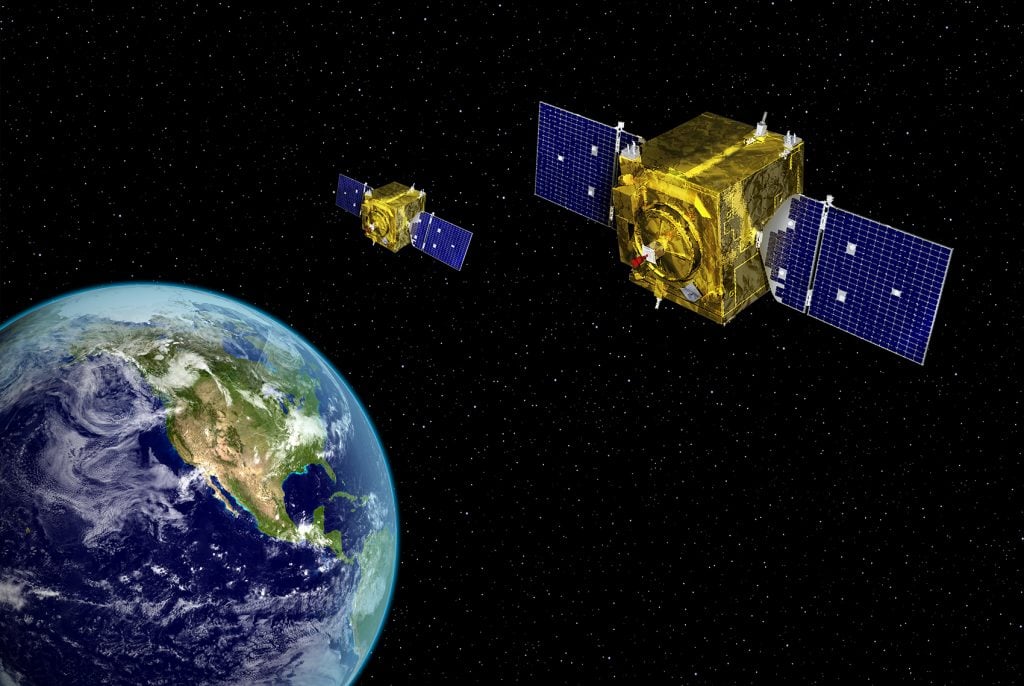

US Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Satellites for “neighborhood watch”

WASHINGTON: The strong congressional focus on national security space programs will continue in this highly contentious election year and beyond — even if the White House changes hands in November, agree the Democratic and Republican chairs of the House Space Power Caucus.

Rep. Doug Lamborn

“On national security space, I think there is a real strong sense in both the House and the Senate to make this a high priority, regardless of what administration sits in the White House a year from now,” Republican Rep. Doug Lamborn, a member of the House Armed Services Committee (HASC) whose district includes Colorado Springs, told a packed house at today’s Space Foundation “State of Space 2020” workshop here today.

He noted that the increased US focus on military space “started in the House … and that was bipartisan” — referring to the years of effort by Reps. Mike Rogers, a Republican from Alabama, and Jim Cooper, a Democrat from Tennessee, to create a new military organization for space. As Breaking D readers are well aware, their work ultimately resulted in the creation of both Space Command and the new Space Force.

Space simply “is not a partisan issue,” said Rep. Kendra Horn, Democratic vice chair of the HASC Strategic Forces Subcommittee.

For example, the House and Senate fully funded the Trump Administration’s request for $72.4 million to stand up the Space Force in the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act, although congressional appropriators whacked that back to $40 million. The Pentagon has asked for $15.3 billion for Space Force in 2021.

Horn admitted that unlike President Donald Trump, Democratic presidential candidates have not paid any attention to either national security or civil/commercial space issues. Democrats in Congress and industry need to do a better job at educating party leadership about the importance of space, she said.

“Democrats need to talk more about the importance of space, and advocate for it,” she said. “It is a lack of understanding about the importance of space and what it means… it is critical.”

Rep. Kendra Horn

Horn has a unique perspective in that she also chairs the Space and Aeronautics Subcommittee of the House Science, Space and Technology Committee, which oversees NASA. She stressed that it is crucial that US national security and civil/commercial goals for space are aligned, rather than conflicting.

For example, she told me after the panel, it is important to make it clear that the building up military space capabilities “is not about fighting” in space, but rather “about protecting and defending” US space assets. While nuanced, her language contrasts with the more pugilistic rhetoric from DoD and the Air Force about “warfighting” and space as a “battlefield.”

That said, she and Lamborn are in agreement that adversaries, including Russia and China, are building up capabilities that can threat US space activities.

Lamborn, in particular, pressed home Russian and Chinese threats.

He voiced concern about the fact that a pair of Russian maneuverable satellites, Cosmos 2542 and Cosmos 2543, have been “shadowing” a US KH-11 spy satellite, US 245 operated by the National Reconnaissance Office, since early this month. “It’s very troubling,” he said, noting that Gen. Jay Raymond, in a yesterday interview with colleague W.J. Hennington, had called it “unusual and disturbing” that the Russian sats came within 100 miles of the US satellite.

As Breaking D readers know, DoD and military leaders for many years have been concerned about Russia’s increased focus on maneuverable satellites. That includes both the 2017-launched Cosmos satellites based in Low Earth Orbit (LEO, up to 2,000 kilometers in altitude), where most Earth imaging reconnaissance satellites are based, and the Luch/Olymp in the lucrative Geosynchronous Orbit (GEO, 36,000 kilometers) where most commercial and military communications satellites are based, as well as a number of high-dollar, classified signals intelligence satellites.

For their part, the Russians insists that these satellites are “inspector” satellites for benign space surveillance purposes, such as keeping an eye on dangerous space junk. Further, the Russians have pointed out that the US operates similar satellites that similarly have approached Russian military satellites — including the Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP) “neighborhood watch” satellites.

Lamborn also said he is worried about Chinese efforts to establish an exploration base at the Moon’s southern pole by 2024, explaining that in his view everything China does in space has a military aspect (a view that Chinese officials of course would object to). Therefore, he said, perhaps NASA may want to rethink its plans for a return to the lunar surface by 2028.

“Maybe we need to match the 2024 Chinese goal, so they don’t get a leg up on us when it comes to the security implications of them having a permanent presence on the Moon,” he said, noting in particular that it would give Beijing an advantage in space and Earth surveillance.

Lamborn mused that perhaps when Russia and China become as dependent upon space as the US is for power projection, they will perhaps be more leery of taking actions that might result in the US feeling the need to attack their space systems.

“I think maybe there is a mutual assured destruction in space, kind of like in the nuclear program for decades, where no one will go there because the consequences will be too severe,” he said.

Major trends and takeaways from the Defense Department’s Unfunded Priority Lists

Mark Cancian and Chris Park of CSIS break down what is in this year’s unfunded priority lists and what they say about the state of the US military.