The USS Warner under construction in Newport News, one of the last two shipyards in the US able to build a nuclear-powered submarine.

WASHINGTON: House defense appropriators voted Wednesday to back the House Armed Services Committee’s bid to restore full funding for a Virginia-class attack submarine that the Trump Office of Management and Budget cut at the last minute.

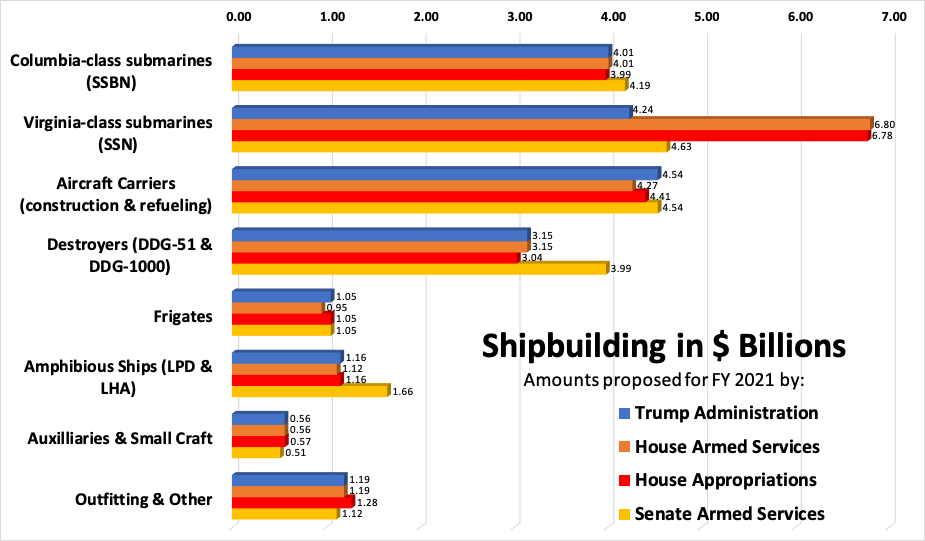

Adding over $2.5 billion for the submarine puts the Democrat-controlled House on a collision course with the Republican-led Senate Armed Services Committee, whose funding tables only added a net $398 million — effectively a down payment, not a complete boat. Conversely, the SASC added $905 million to the request for destroyers and amphibious ships, while the two House committees actually trimmed those two categories. (HASC and House Appropriations have slightly different numbers).

Yet to be heard from is the fourth and final piece of the annual defense spending jigsaw in Congress, the Senate Appropriations Committee. (The process is arcane, but in essence, spending increases must be approved by both the authorizers – i.e. the armed services committees – and the appropriators in both chambers). If the Senate appropriators side with their Senate Armed Services colleagues, they’ll set the ground for a multi-billion-dollar battle between the two chambers. If Senate appropriators side with the House, it’ll be hard indeed for SASC to stand alone.

Prudent Or Too Slow?

Why did Senate authorizers decide to diverge so sharply from the House? It’s surprising, especially since the ranking Democrat on SASC — who’s also a member of Senate Appropriations — is Rhode Island’s Sen. Jack Reed, a longtime booster of submarines, half of which are built in New England.

But the SASC has concerns about changes the Navy wants to make to future Virginia submarines. The most prominent is the Virginia Payload Module, which lets the boat carry 28 more Tomahawk missiles – a 76 percent increase – at the cost of lengthening the hull by 84 feet – a 22 percent increase in the sub’s size. It’s a major upgrade driving a comparable increase in complexity and cost. All but one of the 10 Virginia submarines on the current multi-year contract, including the one the Trump Administration tried to cut (over the Navy’s objections), are intended to be the VPM variant.

The VPM and other changes to the would be challenging at any time. But at the same time the shipyards are going to build the bigger-and-better Virginias, they’ll also have to start production on the even larger Columbia-class submarine – whose ballistic missiles will be crucial to the nation’s nuclear deterrent. That’s a tremendous challenge for the industrial base that the Navy, Congress, and outside experts have worried about for years.

A Navy depiction of the future USS Columbia nuclear missile submarine (SSBN 826)

SASC argues there’s still time to get this right. Typically, a new submarine is funded over three years: two fo Advance Procurement, focusing on time-consuming items like the reactor, and a final year of funding to finish the boat. “Our understanding from Navy officials,” a SASC staffer told us, “is that either providing the remainder of the funding in FY21 or providing this funding in the traditional profile, phased over FY21-23, would support the planned construction schedule for the option submarine.”

Why would lining up all the funding by 2023 still get it done on time? “Construction on this additional submarine would not begin until March 2024,” says SASC’s report language. “[The] typical procurement funding profile [i.e. spreading funding over three years] would also provide additional time to more fully assess previous concerns of Navy officials regarding the ability of the submarine industrial base to build 10 Virginia-class submarines, with 9 having the Virginia Payload Module in this time frame.”

So the Senate authorizers approve $474 million in 2021 for Advance Procurement, enough to buy the submarine’s reactor core. (They cut $74.4 million from another sub, for a net increase of $389 million to the Virginia program). The rest of the money – over $3 billion more – would have to come in 2022 and 2023.

But it’s not clear the Navy can come up with this additional funding in the out years, especially given the pressure COVID-19 now appears to be putting on future budgets. What’s more, even if the funding does materialize on time, the HASC staff argued this schedule is too slow. The shipyards are feverishly ramping up to build both the upsized VPM Virginia and the mammoth Columbia, which requires new facilities and new hires – growth that the yards planned based on the steady two-sub-a-year rate that previous Congresses had pledged. Cut the Virginia budget for 2021, HASC staff said, and “last in/first out” labor contracts could force the yards to lay off the young workers they just hired to build Columbia.

Breaking Defense graphic from congressional data.

Run Silent, Run The Numbers

While the House and Senate are billions apart on specific vessels, it’s important to note that the three committees are close on the overall shipbuilding budget. Their total figures for the Shipbuilding & Conversion, Naval (SCN) account come to within $800 million of each other, a difference of less than 4 percent:

- The Trump Administration requested $19.9 billion.

- The House Armed Services Committee voted last week to approve $22.1 billion.

- The House Appropriations subcommittee on defense approved $22.3 billion.

- The Senate Armed Services Committee approved $21.3 billion.

Precisely because everyone is trying to stay within roughly the same overall shipbuilding budget, however, any additional money for one type of vessel must come at the expense of something else. The three committees are very close on Columbia, aircraft carriers, the Navy’s new frigate, auxiliary ships, and small craft. But to fund the big increase to Virginia, the House committees forgo the Senate authorizers’ increases to destroyers and amphibious warships:

- The Trump administration requested $3.15 billion for destroyers – two Arleigh Burke-class (DDG-51) ships for the current year, plus some work on other ships – and $1.16 billion for a mid-sized amphibious ship, a San Antonio-class (LPD).

- The House authorizers approved the same $3.15 billion for destroyers but trimmed the amphibious ship to $1.12 billion on grounds of “excessive cost growth.”

- House Appropriations did the opposite, cutting destroyers slightly, to $3.04 billion, while fully funding the amphib, at $1.16 billion.

- The Senate authorizers, by contrast, increased both substantially: SASC voted $3.99 billion for destroyers – mostly additional Advance Procurement for future years — and $1.66 billion for amphibs – enough to start construction on a second, larger amphib, an America-class (LHA).

All these ships have strong constituencies. To some extent those constituencies even overlap: Destroyers and amphibs, in particular, are often built in the same yards. But constructing nuclear-powered submarines requires a highly specialized industrial base. The big debate between House and Senate is how best to keep that sub-building base healthy.

Textron, Leonardo bank on M-346 global experience in looming race for Navy trainer

“The strength we think we bring is that [the Navy is] going to go from contract to actually starting to turn out students much quicker than any other competitors,” a Textron executive told Breaking Defense.