WASHINGTON: Despite the tremendous impact unmanned systems are having on the battlefield, military leaders still struggle to get intelligence gathered from these systems into the hands of those who need it.

WASHINGTON: Despite the tremendous impact unmanned systems are having on the battlefield, military leaders still struggle to get intelligence gathered from these systems into the hands of those who need it.

The systems designed to stream raw data collected by the diverse fleet of unmanned systems in the field continued to hamstring combatant commanders and Pentagon leaders alike, Rear Adm. Bill Shannon, the Navy’s program executive officer for unmanned aviation and strike weapons, said today. These systems are designed to handle the back-end of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance operations.

The problem with those processing, exploitation and dissemination (PED) tools is that there is no commonality between the various systems build to do that job, Shannon said. It has become a monumental task to shift data between the various service-centric relay nodes that take data from UAS and move them into the PED cycle. Questions over who needs to have access to what data and how to move data across services have been hurdles for which DoD strategists have yet to find solutions.

Top Pentagon brass began to tackle the problem in earnest in 2008, when then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates criticized the services — particularly the Air Force — for not providing enough UAS to combat commanders in Southwest Asia. During his speech at the Air War College, Gates infamously said getting UAS assets into the field was “like pulling teeth”. Shortly thereafter, all the services began flooding the seas and skies with unmanned systems. But that increase created problems for service intel analysts, who suddenly were inundated with reams of raw data collected by these new assets. That problem continues to this day, according to Shannon.

Since then, steps have been taken to help streamline that PED process, the two-star admiral said. DoD has been mulling ways to establish a set of common protocols and processes to help ease pressure off of service analysts. Even with those changes, the systems managing the PED process are too tied to the specific services. The problem is that with the boom in UAS operations, the number of stakeholders DoD must please in developing a common PED process has skyrocketed, Shannon said. That is akin to “boiling the ocean” where it’s almost guaranteed someone won’t be satisfied. As DoD tries to wade its way through that process, the services have begun their own work to find commonality in their own UAS portfolios.

Navy and Air Force leaders are already taking steps towards this goal. Service leaders are working on a common ground control station for the Air Force’s Global Hawk and the Navy’s Broad Area Maritime Surveillance UAS, based on the Global Hawk. Shannon’s shop is looking at levels of commonality between UAS systems and the Navy’s surface warships, he said. Those “levels of integration” could be key in getting ships and drones to work together. And Navy leaders are installing ISR support systems into their fleet of amphibious ships, Marine Corps Col. James Rector, program manager for small tactical UAS systems at Naval Air Systems Command said at the Association of Unmanned vehicle Systems International conference here today..

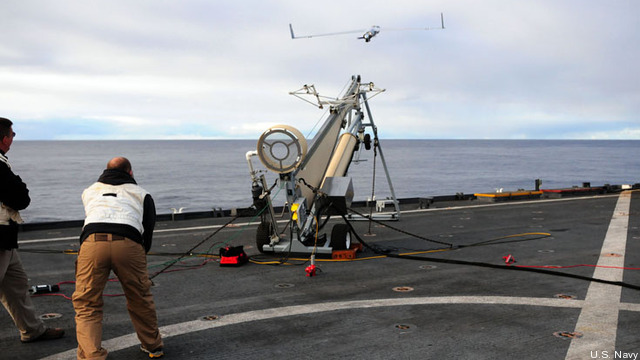

ISR support systems, focusing on PED work, are being installed aboard the USS Gunston Hall and USS San Antonio, he said. The goal is to have a ship-based ISR support system for each Marine Expeditionary Unit in the service. These systems will support the new RQ21A Integrator, which will be the service’s primary Small Tactical UAS system, once it’s fully developed.

Anduril, South Korean shipbuilder HD Hyundai announce new partnership for autonomous systems

US Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro has praised South Korean shipbuilders such as HD Hyundai at recent events, encouraging more participation with US industry.