WASHINGTON: “If we’re going to fix it, we’re going to have to take some risks.”

WASHINGTON: “If we’re going to fix it, we’re going to have to take some risks.”

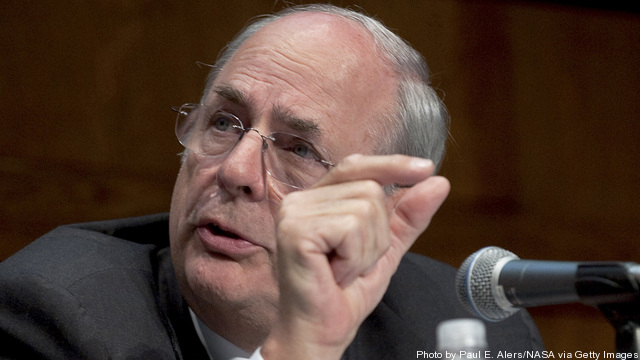

That’s the core of Norman Augustine’s vision for Pentagon acquisition reform: He who dares may not always win, but he who doesn’t dare never will. The military’s system for buying weapons is so afraid of failure, the legendary former Lockheed chairman told Breaking Defense on Friday, that it makes even its successes needlessly expensive and painfully slow.

“In spite of all our troubles we have, I think every nation in the world would trade its equipment for ours,” said Augustine, who’s worked in both business and the Pentagon. “Our system has produced great things. It’s just done it with dreadful inefficiencies.”

“The blame, if that’s the right word, is widely shared between the administration and Congress and industry,” he went on — “and I might also throw in the impact of the media here,” since it tends to jump up and down screaming at any failure. “If something goes wrong,” he said, “the downside is so great that those in the government become very risk-averse, so they take all kinds of steps to prevent anything from ever going wrong. The objective of the system becomes ‘don’t let anything go wrong,’ rather ‘let things go right.'”

As a result, “every time something goes wrong we add a regulation that says, ‘don’t let that go wrong’; so basically our regulations are just a huge pile of band-aids one on top of the other. You can’t manage by regulations,” Augustine said. “You manage by the judgment of competent people.”

“My simple philosophy of management [is] find good people, tell them what you want, and get out of the way,” he said. “That leads to great success; it also leads to occasional failures. The DoD system can’t stand those occasional failures” — but the over-regulation and micro-management meant to leave no room for failure instead leave no room for success.

Instead, it’s essential to “delegate authority, delegate responsibility, and hold people accountable — things that are done in industry routinely that government finds its very difficult to do,” Augustine said. “Some of them will not do a good job, [so] you replace them quickly.”

“On average you’ll be way ahead,” he said, “but there will be those outliers where things go badly, and that’s part of the price of doing tough things.”

Augustine argues that when we do exempt programs from the normal over-oversight, the results prove his point, with notable successes both in the rapid equipping process for the post-9/11 wars and high-priority programs during the Cold War. “Many of the finest systems we have were built outside of the usual acquisition process,” he said. “You can go all the way back to the Polaris [missile], to the nuclear submarines, to the SR-71, to the U-2 — to some degree, the F-16.”

Each of those programs had top-level support and resources to push it ahead, but equally important, “not a lot of people were allowed to dabble,” he said. “The program managers were really allowed to run those programs…. We’re just not culturally prepared to do that for all programs.”

Trust in subordinates and willingness to take risks has to run all the way through the system, Augustine said, or no amount of structural reform and reorganization will solve the problem — as years of well-intentioned failures have shown. “Is the Congress really willing to give the authority to the DoD to run its affairs? Is the DoD willing to delegate that authority to a handful of really competent individuals to run the programs?” he asked. “The answer in the last 50 years has been no.”

Multi-ship amphib buy could net $900M in savings, say Navy, Marine Corps officials

Lawmakers gave the Navy authorities to ink a multi-ship amphib deal years ago, but the service has not utilized that power yet.