The cruiser USS San Jacinto (near) sails side by side with the Russian destroyer Admiral Chebanenko (far)

WASHINGTON: “When I was an ensign, a lieutenant, we knew we could beat the Russians. It was just a question of time because we were better than them,” NATO’s top admiral said. “I’m not sure we could make that assumption now.”

Vice Adm. Clive Johnstone, Royal Navy

The European allies suffer many shortfalls at sea, said Vice Adm. Clive Johnstone, the Royal Navy officer heading NATO’s Allied Maritime Command (MARCOM): anti-submarine warfare, missile defense, munitions stockpiles, sealift, cybersecurity, even the command and control capabilities of his own 300-strong headquarters.

So, I asked the admiral at an Atlantic Council event, would coastal waters within range of Russian land-based missiles — like the eastern Mediterranean near Syria, the northern Black Sea, and the entire Baltic — be no-go zones for NATO navies in event of war? Would any NATO vessel in those areas during a crisis be effectively held hostage by the Russians?

“No and no,” Johnstone said. “We are not ceding ground and we wouldn’t put people in as hostages.”

To the contrary, the admiral argued, NATO navies must assertively patrol those areas, contest control of them, and not “cede space” to the Russians. That means, he said, sailing as close as 15 miles from the Russian base in Tartus, Syria, for example. It means, instead of treating the Black Sea as Russia’s “private lake” and only sending lightly armed auxiliaries there, NATO needs to send full-up warships capable of defending themselves from air and missile attack, as it did recently with the HMS Duncan, a British Type 45 destroyer. It means planning a “holistic” air and naval campaign in the Baltic to establish and sustain a forward presence there, starting long before the first shot is fired.

A Russian Su-24 buzzes the USS Cook in the Baltic Sea, April 12, 2016.

Once a war starts, “to fight your way through and get presence is really going to be militarily quite demanding,” Johnstone said with typically British understatement. “We have rehearsed that,” he said, but it’s far better to have forces in place from the start.

Those forces have to come from all of NATO, not just the Baltic States themselves. That’s no slur on the Estonian, Latvian, or Lithuanian navies. “They’re genuinely brilliant, they are delivering capability to (NATO) Standing Naval Forces in a way that I think should embarrass some bigger nations,” he said. “But they’re small nations. (They’re) not going to win the war. they’re going to be brave and hold the line, and we’re going to have to bring in other capabilities.”

The threat isn’t limited to waters close to Russia, either, Johnstone said. Russian warships and submarines now frequently deploy well out into the Atlantic Ocean, he said. These vessels are armed with Kalibr cruise missiles that could threaten US reinforcements headed to Europe in a crisis, creating an extended Anti-Access/Area Denial zone.

“The A2/AD challenge might not be coming from Eastern Europe,” Johnstone said. “The A2/AD may come from the central Atlantic.” Johnstone is already conducting exercises on how to provide escort ships and land-based air cover for convoys crossing the Atlantic, he said.

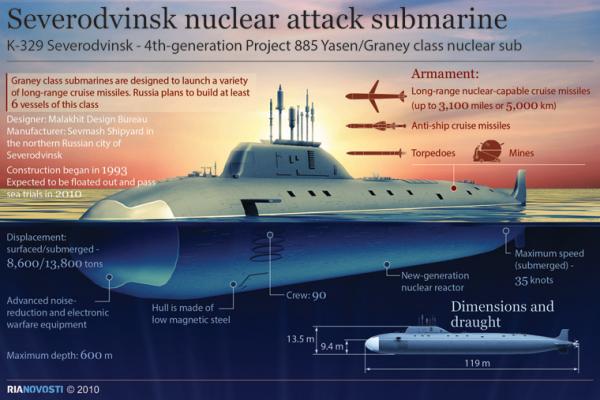

Russia’s most advanced attack submarine, the Severodvinsk class. (Navy graphic)

Command & Control

NATO leaders are now considering re-creating the Cold War-era Atlantic Command. There’s also work to stand up a new Joint Forces Command-X for naval operations, probably US-led, alongside NATO’s existing JFCs. Johnstone’s MARCOM, created shortly after the invasion of Ukraine, would complement a future Atlantic Command and/or JFC-X, not compete with them, he said.

In fact, MARCOM’s explicit mandate is to conduct operations in peacetime and crisis, but not to run a shooting war. If “kinetic” operations became necessary, Johnstone said, MARCOM would hand over command and control to a “heavy metal” warfighting force, “which will only be commanded by an American.”

NATO is still thrashing out how such a handoff would work. It would be particularly tricky, I noted, because modern Russian strategy deliberately blurs the line between war and peace and create a grey zone through use of propagandists, hackers, saboteurs, proxy forces, and deniable “little green men” — Russian soldiers without insignia.

That’s true, Johnstone acknowledged. In a recent exercise called Trident Javelin, in which MARCOM for the first time was certified to act as a NATO “battle staff,” his HQ handled simultaneous naval conflicts in the Baltic and Norwegian Seas, he said — but what was really hard to deal with was the grey zone activity around Europe.

“The game players moved the crisis almost clockwise around the sector ending in up Germany.” he said. Events that initially seemed unrelated to the conflict would shut down a port or a shipping company, throttling NATO supply lines.

MARCOM is now working with NATO special operations on how to counter such sabotage and subversion, he said: “We’re in the fledgling stages of how we deal with it,” he said. “They’re a long way advanced.”

Russian SPETSNAZ special forces

Shortfalls To Fix

MARCOM is getting more funding to improve its command and control network, Johnstone said. His headquarters must link to 17 nation’s networks with widely varying levels of security, ultimately connecting ships with different hardware, software, and security cultures. The whole system is only as secure as its weakest link. “It’s scary,” he said. “We’re in a massive health drive within my headquarters and in NATO navies” to improve cybersecurity.

Other shortfalls, however, will require NATO’s European members to increase spending on their own capabilities:

- ANTI-SUBMARINE WARFARE: “We have found over the last two years that we are very short of very high-end anti-submarine warfare,” Johnstone said. “We’ve been struck by the massive investment it takes to hunt even a Kilo submarine.” The Kilo class is the standard-issue diesel subs first built by the Soviets in the 1980s.

- MISSILE DEFENSE: With Russian submarines, surface ships, and land bases like Kaliningrad all armed with long-range missiles, NATO needs “a proper conversation (about) how do we do missile defense,” Johnstone said. “Have we got the right missile defense capabilities? And I am not sure we have.”

- SUPPLY: “One of the things that worries me (is) the industrial reserve,” Johnstone said. “How much war stocks are back at home? How able is the industrial base to support a really rapid ramp up?

- SEALIFT: “Do we have enough heavy lift and stuff? No,” Johnstone said. However, he said, there’s tremendous potential to move troops and supplies in both commercial vessels and relatively low-cost amphibious warships. In the high-threat environment around Europe, he said, the value of amphibs is as fast transports, not to storm coastlines defended by missile batteries. “What worries me a bit,” he said, “(is) we are having a conversation about amphibiousity and amphibious capability as though… it’s D-Day and we’re going across the beaches.”

Iran says it shot down Israel’s attack. Here’s what air defense systems it might have used.

Tehran has been increasingly public about its air defense capabilities, including showing off models of systems at a recent international defense expo.