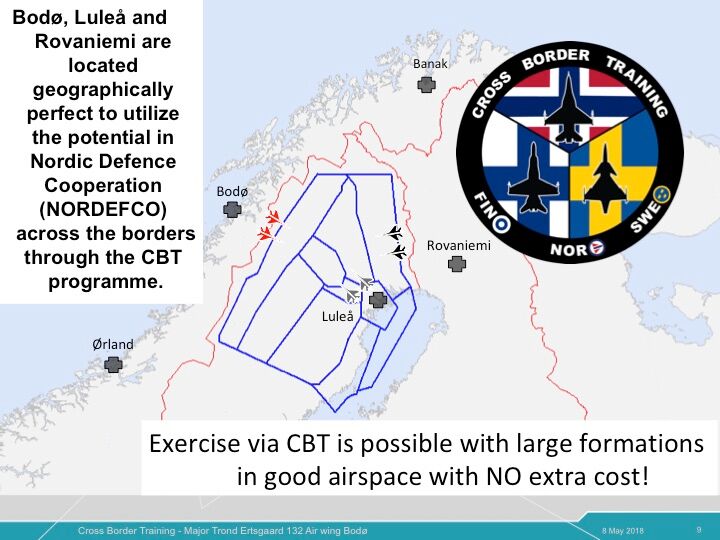

Nordic Cross Border Training airspace map

During the past couple of years, I’ve focused on the part of Europe which is very serious about defense, namely, Northern Europe. The Danes, the Norwegians, the Swedes and the Finns, all have refocused efforts on defense of their nations, but they’ve done so in a broader regional context.

As my colleague Harald Malmgren put it in his analyses of the evolution of Europe:

A new “cluster” of European nations with a common security objective has quietly emerged recently in the form of focused military cooperation and coordination among the Nordic nations, Poland, the Baltic States, and the UK. This cluster is operating in close cooperation with the US military. The Danes, Norwegians, the Swedes and Finns are cooperating closely together on defense matters. Enhanced cooperation is a response to fears of Russian incursions, which are not new, but have roots in centuries of Russian interaction with Northern Europe.

During my most recent visit to Norway in April, I discussed the upsurge in cooperation of the five-member Nordic Defence Cooperation (NORDEFCO) states. Its members are Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden.

As one Norwegian senior analyst put it during my visit: “How far can we take our NORDEFCO cooperation? We now have a mission paper which extends our framework of cooperation through 2020, and we are working a new one which extends the horizon to 2025.”

The members are working on an “easy access agreement” whereby the forces of the member states can cross borders easily to collaborate in exercises or in a crisis.

During my visit to Bodø Airbase on April 25, 2018, I discussed the cross border air training which Norway is doing with Finland and Sweden. Norway is a member of NATO; Finland and Sweden are not (though both states cooperate with NATO).

The day I was there, I saw four F-16s take off from Bodø and fly south towards Ørland airbase to participate in an air defense exercise. The day before this event, the Norwegians contacted the Swedes and invited them to send aircraft to the exercise, and they did so. The day before is really the point. This is a dramatic change from the 1990s, when the Swedes would not allow entering their airspace by the Norwegians or Finns without prior diplomatic approval.

Maj. Trond Ertsgaard, senior operational planner and fighter pilot from the 132 Air Wing, provided an overview to the standup and the evolution of this significant working relationship. The core point is that it is being done without a complicated day-to-day diplomatic effort: “In the 1970s, there was limited cooperation. We got to know each other, and our bases, to be able to divert in case of emergency or other contingencies. But there was no operational or tactical cooperation. The focus was on safety; not operational training.”

By the 1990s, there was enhanced cooperation, but it was limited to a small set of flying issues, rather than operational training. As Ertsgaard noted: “But when the Swedes got the Gripen, this opened the aperture, as the plane was designed to be more easily integrated with NATO standards.”

Then in the Fall of 2008, there was a meeting of the squadrons and wing commanders from the Finnish, Swedish and Norwegian airbases to discuss ways to develop cooperation among the squadrons operating from national bases. The discussion was rooted on the national air forces operating from their own bases and simply cooperating in shared combat air space. This would mean that the normal costs of hosting an exercise would not be necessary, as each air force would return to its own operating base at the end of the engagement.

The CBT started between Sweden and Norway in 2009 and then the Finns joined in 2010. By 2011, Ertsgaard highlighted that “we were operating at a level of an event a week. And by 2012, we engaged in about 90 events at the CBT level.”

That created a template which allowed for cost effective and regular training and laid the foundation for then hosting a periodic two-week exercise where they could invite nations to participate in air defense exercises in the region. From 2015 on, the three air forces have shaped a regular training approach, which is very flexible and driven at the wing and squadron level.

“We meet each November, and set the schedule for the next year, but in execution it is very, very flexible. It is about a bottom-up approach and initiative to generate the training regime,” Ertsgaard said.

The impact on Sweden and Finland has been significant in terms of learning NATO standards and having an enhanced capability to cooperate with NATO air forces.

The air space they are operating in is very significant as well. Europe is not loaded with good training ranges. The range being used for CBT is very large and is not cluttered, which allows for great training opportunities for the three nations, as well as those who fly to Arctic Challenge or other training events. And the range includes land portions so there is an opportunity for multi-domain operational training as well.

What is most impressive can be put simply: CBT was invented by the units and the wing commanders and squadron pilots. The CBT led to the launching of the Arctic Challenge Exercise. This exercise, last held in 2017, has seen both the regional air forces and partner air forces engage in a major training exercise in the region as well.

According to the US Department of Defense, the Arctic Challenge exercise in 2017, “aims at building relationships and increasing interoperability, and includes participants from the U.S., Finland, Sweden, Norway, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Canada and the Netherlands, as well as representatives from NATO.”

During my visit to Finland in February of this year, the Finnish side of the story was highlighted in a discussion with former Chief of Staff of the Finnish Air Force, Lt. Gen. Kim Jäämeri, who is now deputy Chief of Staff of strategy for the Finnish Defence Forces: “We have enhanced our focus on crisis management and the role of the military within overall crisis management. We have increased our investments in force readiness. With regard to our partners, their enhanced focus of attention on defense, whether it be the actions of Sweden, Norway or Denmark in the region, or by the United States within NATO with regard to the EDI-related investments, has been appreciated. And as we expand our exercise regime, we are cross-learning with regard to capabilities necessary for our defense. You have to leverage your partnerships more to enhance crisis stability.”

In short, the Russians have had a key impact in revitalizing the Nordic countries’ defense postures. Let us hope the allies of the Northern European states interact with and support this strategic opportunity for shaping an effective extended deterrence strategy and for the defense of the region and beyond.

As Keith Eikenes, director for security policy and operations in the Norwegian Minister of Defence, put it in my final interview during my recent stay in Norway: “What type of assets, forces, structures, and cooperation with allies do we need in order to have effective deterrence in the future? We must never lose sight of the fact that what we are trying to do is actually avoid a conflict. Getting the deterrence piece will be extremely important to shaping a way ahead.”

Given the strategic location of the air space in which CBT training and the Arctic Challenge Exercise is occurring, it is a key part of working deterrence in depth in the region and beyond.

Connecticut lawmakers to grill Army, Lockheed about job cuts at Sikorsky helicopter unit

“The Connecticut delegation has questions about why, with that [FY24] appropriation in hand, this happened,” said Rep. Joe Courtney, D-Conn.