CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & INTERNATIONAL STUDIES: The Air Force threw out two big numbers this week, but one of Washington’s leading budget analysts doesn’t think either of them is credible.

One is the service’s unsolicited estimate that President Trump’s plan to create an independent Space Force – largely carved out of the Air Force – would cost $13 billion over five years. CSIS scholar Todd Harrison says that’s a crudely inflated figure, probably intended to undermine the Space Force proposal by scaring off potential supporters. While Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson has called the $13 billon figure “conservative,” Harrison told reporters this afternoon that: “this is not a conservative estimate….This is the highest estimate I think you could possibly come up with.”

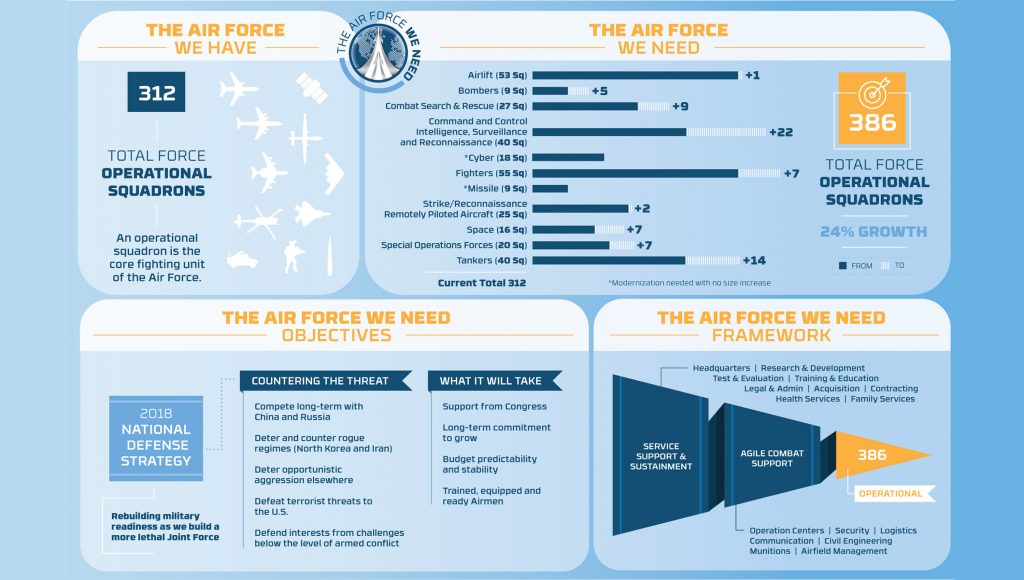

The other is the service’s bold plan to grow by 24 percent to 386 squadrons, with no cost figure provided. (That includes space assets, which the plan presumes the Air Force will retain). Harrison guesstimates that the additional personnel, maintenance, fuel, and other operating costs would cost about $18 billion a year. That’s $90 billion over five years, not counting any new aircraft, compared to the (inflated) $13 billion to stand up the Space Force. But since the Air Force hasn’t yet specified how many aircraft of what types the new squadrons will have, let alone overhead costs for training, basing, and administration, it’s impossible to calculate a true cost.

So, I asked Harrison more than once, you’re calling all this B.S.? He just chuckled and said, “I am not using profanity.”

$13B Space Force: Inflated

No one actually asked the Air Force to estimate the cost of the Space Force. Deputy Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan had asked Undersecretary for Research Mike Griffin and Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson to submit alternative plans for creating one of the key components, a Space Development Agency. But Air Force leaders from Wilson down had publicly opposed giving up their space assets to a new service – until President Trump unexpectedly embraced the idea – and apparently took Shanahan’s request as an opportunity to “sabotage” it, as Harrison said earlier this week.

“This is an example of ‘malicious compliance,'” Harrison said today.

It’s also methodologically crude, he said. The $13 billion estimate simply guess how many people the Space Force might require and then multiples that number by $175,000, then adds $1 billion for a new headquarters building.

That $175,000 per person figure is higher than the defense-wide average fully burdened cost of personnel, Harrison said, but is not unreasonable for an organization full of high-ranking and/or technically expert people. But it’s multiplied by a number of personnel that comes out of nowhere.

Some of the people the Air Force counts wouldn’t strictly speaking even be in the Space Force. They’d be at the new inter-service Space Command, a separate part of the Trump administration proposal. The estimate also assumes the Space Force takes over, not only the existing space components of the four armed services, as per the Trump plan, but space-related elements of the Missile Defense Agency, DARPA, the Intelligence Community (including the National Reconnaissance Office), and the Commerce Department, as well as much of NASA – none of which was in the administration plan.

Even for the pieces that definitely will be part of the Space Force, the personnel estimates are raw numbers without justification. “They’re giving no indication of where they got the numbers of people in this, and this all hinges on the number of people,” Harrison said. “I don’t give a lot of credibility to this.”

386 Squadrons: Too Vague

While the Air Force has high-balled the cost of the Space Force, which it opposes, it’s not even given a cost estimate for increasing its own size, which it supports. Specifically, as Secretary Wilson laid out at this week’s Air Force Association conference, the service wants to add 74 squadrons – growing 24 percent, from 312 today to 386 – and about 40,000 active-duty personnel – growing 12 percent, from just over 325,000 today to about 365,000.

What would that cost? 40,000 people would add $5 billion a year, Harrison said, though some of that would be paid out of defense-wide healthcare accounts rather than the Air Force budget. Then, he said, if you assume the new squadrons of bombers, fighters, transports etc. are the same average size as existing ones, with the same mix of active duty units operating full-time and Guard/Reserve units operating part-time, the operations and maintenance cost would be about another $13 billion a year.

But the Air Force would need more planes and other equipment for these squadrons, including new types either just entering production or not in production yet at all. The five new bomber squadrons could only be equipped with the forthcoming B-21 Raider, since the B-52, B-1, and B-2 production lines are all shut down. The 14 new tanker squadrons could only use the new KC-46, since the KC-130 and KC-10 are, again, out of production. The seven new fighter squadrons would presumably use the F-35A, which is ramping up production and driving costs down. The 22 new Command, Control, Intelligence, Surveillance, & Reconnaissance (C2ISR) squadrons would use aircraft not yet invented, since the Air Force says current C2ISR planes like JSTARS, AWACS, and Rivet Joint are too big and unstealthy a target for future wars, but it’s still working out what to replace them with.

Since the Air Force only says how many squadrons of each kind it wants (bomber, fighter, tanker, etc.), but not how many planes each will have or of what types, and the cost for new types of aircraft is in flux anyway, any cost estimate for the equipment would be pure guesswork. What’s more, not do Air Force squadrons vary widely in size and composition, they’re not self-sufficient: They’re organized into air wings and stationed on bases, both of which have extensive but essential overhead such as, for example, maintenance facilities and runways.

Whatever the final cost turns out to be, Harrison said, it’ll probably more than the Air Force can actually afford. Even if Budget Control Act caps on spending don’t return in 2020, he said, the service is already committed to building many new weapons systems: Not just the B-21 and KC-46, but the T-X trainer, the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) ICBM to replace the aging Minuteman, a new Combat Search And Rescue (CSAR) helicopter, and more. That’s a huge bill just to reequip existing units, let alone equip new units.

“Growing the force is going to compete directly with modernizing the force,” Harrison said. The Air Force probably can’t do both at once.

In a ‘world first,’ DARPA project demonstrates AI dogfighting in real jet

“The potential for machine learning in aviation, whether military or civil, is enormous,” said Air Force Col. James Valpiani. “And these fundamental questions of how do we do it, how do we do it safely, how do we train them, are the questions that we are trying to get after.”