CAPITOL HILL: The military’s new cyberspace force is working to overcome recruiting and retention shortfalls, training bottlenecks, and its dependence on the National Security Agency, officials told the Senate Armed Services Committee yesterday.

These devils in the details are an inevitable part of standing up a new kind of force for a new kind of warfare, one where China and Russia are currently ahead. The Cyber Mission Force’s struggles are also a cautionary tale for the Trump Administration’s plans to stand up a separate Space Force.

On May 4, Cyber Command was officially elevated to a full combatant command co-equal to STRATCOM, CENTCOM, et al. Two weeks later, CYBERCOM’s 133-team, 6,200-plus-person Cyber Mission Force officially achieved Full Operational Capability (FOC).

On May 4, Cyber Command was officially elevated to a full combatant command co-equal to STRATCOM, CENTCOM, et al. Two weeks later, CYBERCOM’s 133-team, 6,200-plus-person Cyber Mission Force officially achieved Full Operational Capability (FOC).

Now comes the hard part.

“While achieving Full Operational Capability of these teams was an important milestone, it certainly is not an end state,” testified Lt. Gen. Stephen Fogarty, head of Army Cyber Command, which provides 41 of the 133 teams. Now CYBERCOM and its four service components — Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine — have to figure out exactly what a team needs to do its mission, the specific training required, and how to measure readiness.

“The number of folks that the services are providing and the level of their training… we have a standard approach for measuring that,” said Lt. Gen. Vincent Stewart, the Marine who’s deputy commander of CYBERCOM. “That’s the easy objective measurement.” The services are providing “fairly capable” people, he said, but it’s up to Cyber Command to “take them from the apprentice and journeyman level to the master level.”

Cyber Command has developed detailed requirements for the intelligence, technologies, and access it needs to perform specific missions, Stewart said. It’s taking the initial, relatively course assessment of what skills mix a cyber team needs, refining it for specific kinds of targets, and formalizing it into official Mission Essential Task Lists (METLs). It’s even reevaluating its initial estimate of the requisite mix of the three critical specialties on a team:

- tool developers, who write the customized code — often exquisitely tailored to the specific target — required for cyber warfare;

- exploitation analysts, who look at the intelligence on a target network and figure out how best to attack it; and

- Interactive On-Net (ION) operators, who probe hostile, friendly, and neutral networks for weak points.

“We started with a number based on our best guess of how we’d operate in this space,” Stewart said. “The reality is we may not need as many IONS, and that will change the training requirements and allow us to do some things that are more creative….We’re working to refine those as we speak.”

Lt. Gen. (then Maj. Gen.) Stephen Fogarty reviews the troops on taking command of the Army Cyber Center at Fort Gordon.

Why IONs Can’t RIOT

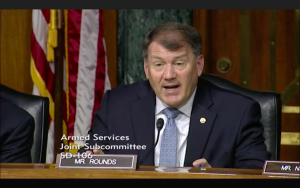

SASC cybersecurity chairman Mike Rounds, who chaired the joint hearing of the cyber and personnel subcommittees, was quick to quiz the Army’s Lt. Gen. Fogarty on key details. Isn’t it true, Sen. Rounds asked, that the Army component of the cyber force is short on critical skills? In particular, Rounds asked, doesn’t the Army need more tool developers and Interactive On-Net (ION) operators?

A big part of the problem is that the Army only gets 15 seats a year for IONs in the National Security Agency’s Remote Interactive Operator Training (RIOT) course. Worse, half of the students the Army sends wash out, a much higher failure rate than the Air Force, which sends more experienced candidates to the course.

Sen. Mike Rounds chairs a joint hearing of the Senate Armed Services subcommittees on cybersecurity and personnel

“You’ve aptly described our challenge with IONs,” Fogarty acknowledged. “We weren’t selecting people who were getting all the way through the course.” What’s more, to help get all the services’ initial contingents through the training bottleneck at NSA, the Army gave the Air Force some of its slots in both the ION and exploitation analyst courses. But the Army can do better with the limited resources it has.

The Army’s come to the realization, Fogarty said, that “not every ION has to be RIOT qualified.” (Yes, cyber guys have more fun with acronyms than the rest of the military). NSA’s RIOT training is required to teach operators to work with NSA’s cyber warfare “infrastructure,” created under Title 50 of the US Code, which governs intelligence. But the armed services have started building their own systems using their own authorities under Title 10, which governs the services. The services can and do conduct their own training programs for these Title 10 systems.

So instead of trying to push all its on-net operators through the bottleneck of NSA Title 50 training, Fogarty said, it’s sending them to the Army Title 10 course first. That gets them to work faster, he said, and then the Army can carefully watch them at work to to pick out “star athletes” who’ll make the most of the scarce spots in the RIOT course.

Fogarty is also working with Gen. Paul Nakasone — who heads both Cyber Command and the NSA — on expanding the RIOT course. But even when that happens, the Army still expects to be selective about who it sends to the NSA training, he said, with most of its IONs trained only on the military’s Title 10 systems.

“As you said very eloquently, we’ve got to get off the NSA platform, become more independent,” said Fogarty, echoing Sen. Rounds’ own opening statement. “The Title 10 infrastructure with Title 10 IONs actually allows us to achieve that goal.”

“Screaming For Ways To Contribute”

The training bottleneck for Interactive On-Net operators is just one piece of the cyber talent puzzle, but it’s important both in its own right and as a microcosm of the larger problems.

These are highly specialized skills that require extensive training. Fogarty testified it takes two and a half years to get a new team member ready for real-world operators, at which point they’re almost halfway through a standard six-year enlistment. What’s more, anyone with potential cyber talent, let alone actual training and experience, is a prime recruiting target for a booming tech industry that offers much better pay — and much less maddening bureaucracy — than the government can for either military personnel or civilians.

The Pentagon has actually done a much better job educating and recruiting military personnel to join the cyber force than it has with federal civilians, said Brig. Gen. Dennis Crall, a Marine who’s the senior military advisor for cyber policy to Defense Secretary Jim Mattis. In fact, testified Essye Miller, the principal deputy to the Pentagon CIO, the cyber workforce as a whole has lost about 4,000 civilians over the last year.

To attract and retain skilled civilians, the Pentagon’s created a Cyber Excepted Service that frees them from many of the usual civil service constraints and provides an ever-growing array of incentives, including greater pay for higher skill. A “very modest” rollout of the CES — with under 400 slots available, all at CYBERCOM, and “only half” the incentives in place — got a strong positive response, Crall testified. Next, he said, they plan to expand the Cyber Excepted Service to 8,300 positions across the services and the Defense Information Services Agency (DISA), with the full package of incentives.

There’s a tremendous pool of cyber talent already in the military, Crall said. The Pentagon just needs to tap into it more systematically by providing the necessary training, technology, and standards. “We have young folks who have zero experience in doing this formally who are writing programs for us today,” he said. “They are screaming for ways to contribute.”

Questions hang over UK’s new, ambitious defense spending plan: Analysts

Such is the scale of British Army acquisition problems alone that they could not be resolved if the UK moved to a long term spending settlement of even 4 percent GDP, an expert told British lawmakers.