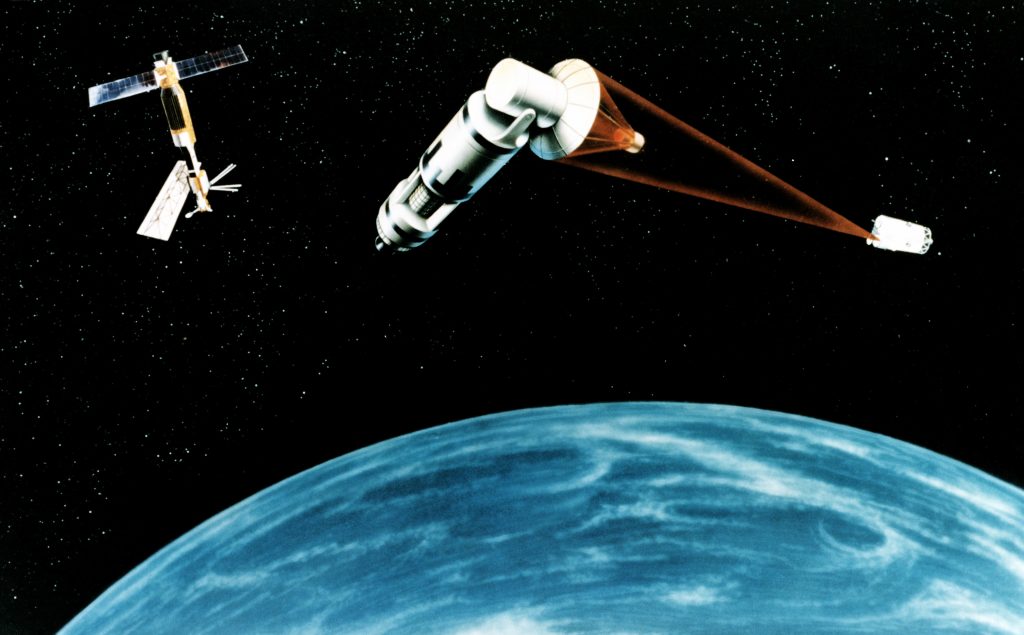

Pentagon R&D chief Mike Griffin wants to revive the idea of space-based lasers for missile defense, a concept he worked on in his youth as part of the Reagan “Star Wars” program, as illustrated here.

WASHINGTON: Despite increasing uncertainty over President Trump’s surprise proposal to cut $33 billion from defense, the Pentagon’s R&D chief says he’s confident more cash will be pumped into laser weapons and new space capabilities.

It should take “no more than a few years” to get directed energy weapons such as lasers into the hands of troops in the field, said Michael Griffin, undersecretary of defense for research and engineering, said this morning at the Center for Strategic & International Studies. But those weapons will likely be Earth-bound in the near-term. While Griffin, a former NASA director, worked on space-based weapons for missile defense under Reagan’s “Star Wars” program and still advocates the idea, he emphasized it will take time to develop sufficiently powerful lasers.

“We need to be in the megawatt class” for space-based missile defense, Griffin said. The most powerful solid-state lasers now in testing are in the 100-plus kilowatt range. The last attempt at one-megawatt missile defense weapon was the Airborne Laser, a 747 full of toxic chemicals that proved too unwieldy for real-world operations, while Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative seriously considered setting off nuclear explosions in orbit to provide the necessary burst of power.

Despite the difficulties, Griffin still sounded confident about funding and building these new capabilities, even in the face of potential budget pressure coming from both a Democratic House and the Trump White House. (Army Secretary Mark Esper took a similarly optimistic stance last week). Griffin even called for a “proliferation” of new sensors in low-earth orbit in order to track hypersonic threats from China and Russia.

“I don’t want to be in any one orbit,” Griffin said. “I want us to be as widely distributed in as many areas of the orbital regime that we can. We are not as prevalent in LEO [low earth orbit] as I would like us to be and I would like to see us proliferate there.”

“We really need to be closer to the action, so that removing a few of those satellites by the adversary doesn’t alter our capability,” he said. “We need to think about space as a domain which our adversaries seek to remove from our use and respond accordingly.”

Chinese air force Col. Wang Zhonghua told a news conference earlier this week the service is spending more on building space capabilities, and “spares no efforts in handling all threats, and is gearing up to extend its reach beyond the clouds and into space.”

Despite moves by the Congress and Pentagon in recent years to decentralize decision making and push authority for acquisition and sustainment programs down to the services, Griffin said these new and expanding capabilities for missile defense and space should remain under the central control of the Office of the Secretary of Defense. That removes some authority from the services, but as Griffin described the move, it would also take away some responsibility to fund the systems.

That should come as good news for the Navy, which would be happy to pass the ballistic missile defense mission off to anyone else who might want it. In June, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson said that the ballistic missile defense patrols are wearing out his ships, which already have plenty of other missions to conduct with a limited number of hulls.

“Right now, as we speak, I have six multi-mission, very sophisticated, dynamic cruisers and destroyers ― six of them (that) are on ballistic missile defense duty at sea,” Richardson told the US Naval War College’s Current Strategy Forum. “So we have six ships that could go anywhere in the world at flank speed, in a tiny little box, defending land.”

Laying his cards of the table, the admiral added, “it’s time to build something on land to defend the land. Whether that’s Aegis Ashore or whatever, I want to get out of the long-term missile defense business and move to dynamic missile defense.”

While Griffin didn’t offer a map to get Richardson’s ships out of those tiny boxes, he did offer him some hope.

“Asking the Navy to prioritize an SM-3 (missile defense) system over another carrier, that’s maybe not a fair question. Asking the Army to prioritize THAAD over another brigade combat team, maybe that’s not a fair question,” Griffin said. “Those are questions of the architecture of what our national defense looks like that maybe rise to the secretary or OSD level, not the responsibility of a given service.”

Before any of those programs can be moved under new management however, the White House and Pentagon need to settle on a new budget, something that looks like it might take some time. The $733 billion budget put together by Defense Secretary Mattis’ team was explicitly designed to support the National Defense Strategy released earlier this year.

The 2020 budget — the Trump administration’s third — was touted by deputy defense secretary Patrick Shanahan late last year as a “masterpiece” that will finally push the Pentagon down the road of building new capabilities, as opposed to filling in readiness gaps.

The 2020 budget “is probably the next biggest step we can take to make sure we can’t unwind the [National Defense Strategy],” he said. “This is where many of the bets, in terms of innovation and some of the new technology, will take place.”

The Pentagon won’t grind to a halt if it receives $700 billion as opposed to $733 billion in 2020, but some of those bets on innovation may have to be scaled back or reconsidered.

Iran says it shot down Israel’s attack. Here’s what air defense systems it might have used.

Tehran has been increasingly public about its air defense capabilities, including showing off models of systems at a recent international defense expo.