SPACE AND MISSILE DEFENSE SYMPOSIUM: The Army is trying out not one but three different small satellite programs over the next few years. The objective: provide direct support from Low Earth Orbit (LEO) — reconnaissance, communications, navigation, and more — to frontline tactical units on the ground.

SPACE AND MISSILE DEFENSE SYMPOSIUM: The Army is trying out not one but three different small satellite programs over the next few years. The objective: provide direct support from Low Earth Orbit (LEO) — reconnaissance, communications, navigation, and more — to frontline tactical units on the ground.

Such smallsat payloads, perhaps hosted on commercial satellites, are an important piece of the Army’s evolving concept of Multi-Domain Operations, which seeks to combine efforts on land, the sea, air, space, and cyberspace to defeat sophisticated adversaries such as Russia and China.

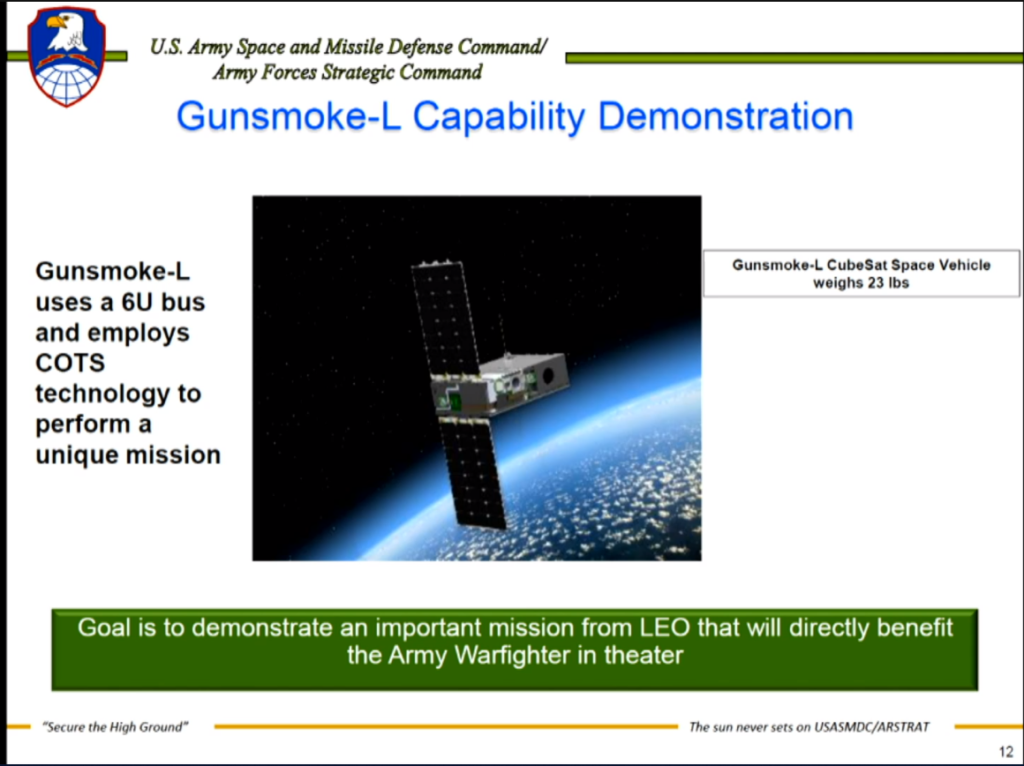

The three new satellite programs are called Gunsmoke, Lonestar and Polaris. We know the most about Gunsmoke, which has been underway since November of 2018, when the Army awarded a two-year, $8.3 million contract tp Dynetics, based here in Huntsville, Ala., to develop, test, integrate and demonstrate two “tactical space support vehicles.”

Lt. Gen. James Dickinson (AUSA photo)

All three programs will demonstrate capabilities on commercial platforms, including “robust PNT [Precision Navigation & Timing] in Low Earth Orbit [LEO],” said the outgoing chief of Army Space & Missile Defense Command, Lt. Gen. James Dickinson. (He’s been tapped to be deputy commander of the new joint Space Command). The Army’s elite modernization Cross-Functional Team for Assured Positioning, Navigation and Timing (APNT) is also interested in demonstrating “advanced commercial manufacturing for military payloads,” he added.

All three efforts build on the Army’s successful demonstration of the Kestrel Eye imaging microsatellite in 2017 to 2018. Kestrel Eye was “designed to be directly taskable and responsive down to the … tactical level,”Dickinson told the Space & Missile Defense Symposium here. And that’s the model for the future, he emphasized: to “deliver, down to the tactical level, space effects” — from recon imagery to jamming-proof navigation — “on tactical timelines.”

“The key to what I just said,” Dickinson stressed, “was ‘down to the tactical level.'”

To support those frontline units quickly and responsively, Dickinson said, Army space forces need bring together US and allied assets, ranging from top-secret national intelligence satellites, to smallsats, to commercial constellations, to high-altitude aircraft. So the Army is developing a “space in-depth concept” designed to support multi-domain operations by the Army itself, the joint force, and foreign partners.

“This is a very crowded operational environment in which space capabilities and applications are essential to success in all domains,” he said, emphasizing that the “Army is the biggest user of space” in the US military.

The Army is also evaluating a number of potential high-altitude alternatives to provide “space-like” capabilities to the warfighter, he said, which could be deployed rapidly as needed in a crisis, to replace satellites destroyed in conflict, or as an alternative to satellite-based capabilities.

The Army has already created a new kind of unit to bring better space support to combat forces, the awkwardly named Intelligence, Information, Cyber, Electronic Warfare, & Space battalion (I2CEWS for short, pronounced “eye-two-cues’). The IC2EWS battalion is part of the brigade-sized Multi-Domain Task Force, which has contributed to at least 10 wargames and shows real potential to defeat the sophisticated layered defenses known as Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD).

Dickinson also reiterated the Army’s long-standing interest in a “robust, persistent” space-based sensor layer in LEO being developed by the Space Development Agency to track missile threats, especially fast, unpredictably maneuvering hypersonic weapons. The service sees the sensor layer as a “critical enabler” for multi-domain operations and “one of DoD’s top priorities,” he said — but “there is a lot of work to do” to develop it.