An Air Force maintainer plugs into the F-35 to perform pre-flight checks — a potential vector for a virus to enter the plane’s on-board electronics.

ARLINGTON: As the military rushes to shore up cybersecurity on the F-35 and other high-tech weapons, Lockheed Martin rolled out a new cybersecurity initiative this morning. Pooling best practices from across the company’s weapons programs, the effort includes a growing database with “hundreds” of requirements and metrics for assessing them, a step-by-step how-to guide for Lockheed cyber staff, and a trademarked Cyber Resiliency Level framework to sum it all up.

The 2016 National Defense Authorization Act required that all weapons begin to be assessed for cyber vulnerabilities, and the 2019 bill kept pressing the effort ahead. Breaking D readers know that Raytheon won contracts to ensure cyber safety for the F-15 and C-130 fleets. But implementing new cybersecurity standards is just the beginning of a much more complex process, Lockheed execs argue, a process in which their deep knowledge of specific weapons systems is vital.

Sure, countless companies combine to spend over a $100 billion a year in the US alone on protecting computer networks. But securing the built-in electronics in a weapons system requires a distinctly different skillset, one where the aerospace titan — with over $50 billion in defense-related revenue last year — believes it has a competitive advantage.

Network cybersecurity is far from easy, but at least you can physically get your hands on your tech to fix it. That’s a lot harder with, say, a top-secret satellite 20,000 miles up: Any software patch you upload has to be transmitted from the ground by radio, and if the problem’s in the hardware … well, good luck getting up there with a wrench. At the other extreme, some military tech is so ubiquitous — guidance chips in missiles, software-defined radios, and so on — that, while it’s physically possible to bring them all in for a fix, it’s impractical and often unaffordable.

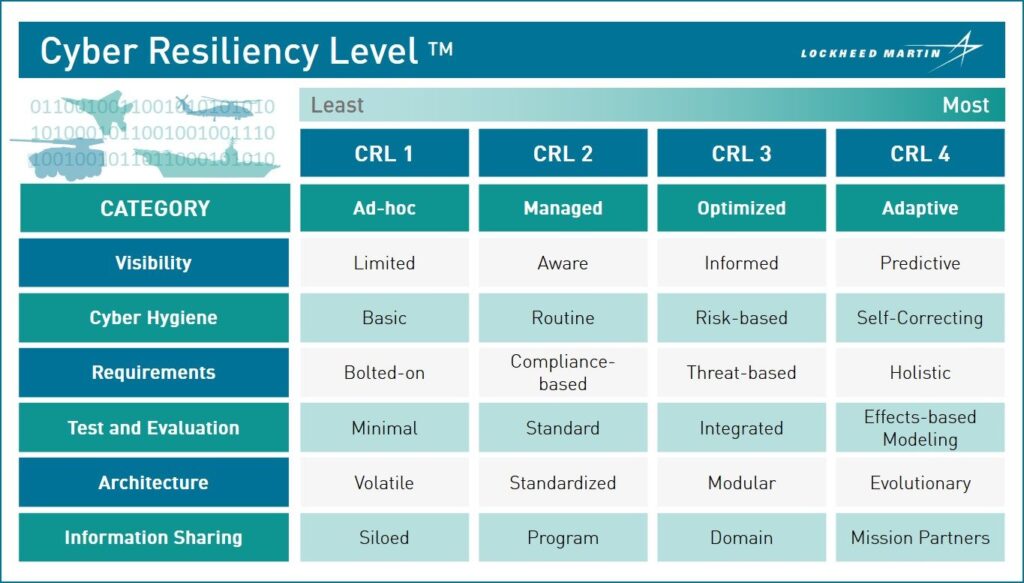

Lockheed Martin’s new Cyber Resiliency Level framework.

For some systems, you might do the cost-benefit analysis and decide to just live with the risk, especially if they don’t connect to anything critical or it can easily be replaced once compromised, Lockheed senior fellow Dawn Beyer told me after the formal briefing this morning. For other weapons, she went on, you might find an affordable fix that, instead of physically replacing problematic hardware, prevents the vulnerable system from being exposed to cyber-infection in the first place. You could increase scrutiny of the firmware in spare parts before they’re installed, for example, or improve training for maintenance technicians before they’re allowed to plug their diagnostic tools into an aircraft, or tighten security at a satellite’s ground control center.

“I could put a card access now on the door so not anyone could walk into the operational floor” for a satellite, Beyer said. “I could change the way I do background checks on the personnel that are working on that operational floor.”

Beyer, a former Air Force intelligence officer, led development of Lockheed’s new Cyber Resiliency Level™ framework (yes, it’s already trademarked), which is intended to help both the company and its clients work out such cost-benefit tradeoffs in a rigorous process. Options range all the way from CRL 1 — say, a legacy weapons system from the 1980s where any cybersecurity is laboriously “bolted on” after the fact — to CRL 4, where automation and even artificial intelligence (AI) react to intrusions in real time.

Lockheed deliberately avoided a five-level system because managers tend to see those and default to level 3, Beyer said. With four levels, there’s no obvious middle-of-the-road and people applying the framework are forced to actually think about it.

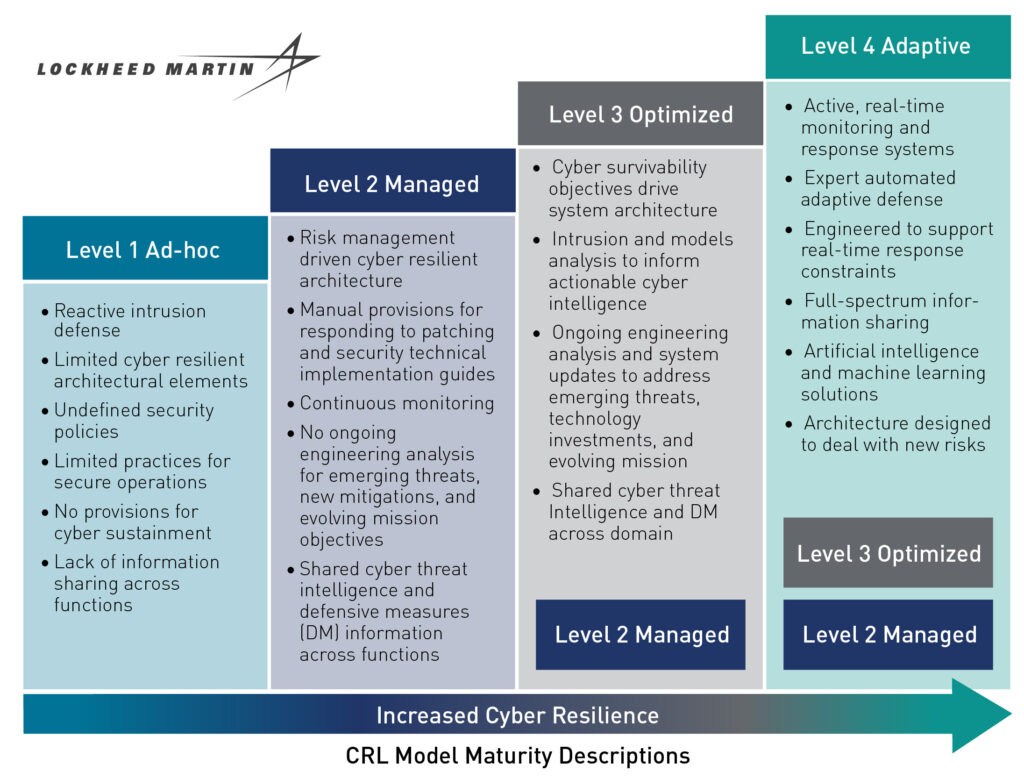

Key steps required at each level in Lockheed Martin’s new Cybersecurity Resilience Level model.

Deciding what security level to shoot for is just the beginning. Next there’s a detailed workbook and an even more exhaustive guidebook on how to actually implement the new approach. The company’s new best-practice databases provide real-life examples of how to turn general cybersecurity standards — from DoD itself, NIST, AIA, and elsewhere — into specific requirements for a program that you can then test realistically against quantifiable metrics. You can even find contact information for Lockheed programs that have successfully overcome similar problems in the past.

Well, you can’t, and I can’t, but select Lockheed employees can. The company is keeping a tight lid on exactly what its procedures, requirements, and metrics actually are, since that’s where its competitive advantage lies. Nor is it saying which programs it has actually used to test out this new approach, although there have been at least 10 pilots, one of them an unspecified military satellite.

“We’re using it. It’s working for us. We’re learning a lot as a result,” says Lockheed government cyber director Jim Keffer, a retired Air Force two-star. The framework has already been revised three times based on internal Lockheed pilot projects and reviews over the last year, he said, in preparation for going public and sharing the new initiative with potential customers. “That’s why we felt really comfortable going forward,” he said, “and saying ‘hey, it’s working for us, it might work for you.’”

Textron, Leonardo bank on M-346 global experience in looming race for Navy trainer

“The strength we think we bring is that [the Navy is] going to go from contract to actually starting to turn out students much quicker than any other competitors,” a Textron executive told Breaking Defense.