SB>1 Defiant compound helicopter, a contender for the Army’s Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) to replace the UH-60 Black Hawk.

AUSA: After decades of cancelled programs, the Army is launching its biggest modernization effort since the Reagan buildup — and the cost will almost certainly exceed the current estimates, the service’s top budget planner warned. Neither internal Army reforms like the Night Courts, nor sympathetic Defense secretaries nor congressional committees will deliver enough money to cover the gap. That puts tremendous pressure on the not-quite-13-month-old Army Futures Command to control costs the way previous generations of generals could not.

Lt. Gen. James Pasquarette, Army Deputy Chief of Staff (G-8)

The Army has been able to fund all its top priority initiatives so far, said Lt. Gen. James Pasquarette, the deputy chief of staff (G-8) in charge of building long-term budget plans. “Right now, as quickly as they have a requirement, we’re funding it, as quickly as we can,” he told me and another reporter yesterday. But that may well change, he warned, as relatively small-scale prototyping and experimentation scale up to producing, testing, and fielding enough equipment for entire combat units.

“We don’t really have a clear picture of what those bills are right now,” Pasquarette told an Association of the US Army breakfast. “The [long-term budget] program’s what we think they’re going to be, but I think as we fully transition from RDTE [Research, Development, Test, & Evaluation] to procurement, there’s unrealized bills out there that we’re going to have to figure out how to resource. Right now, I think they’re underestimated.”

Pasquarette’s staff is now preparing to build the long-term budget plan that will take the Army through the end of 2026. Between now and then, he told the Association of the US Army here, 10 major programs will need funding to move into production, four of them in 2021 alone:

- The initial version of the Integrated Tactical Network (ITN) to coordinate combat operations, which will then receive major upgrades every two years;

Anti-aircraft Stryker variant chosen by the US Army for its Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense (MSHORAD) mission: 4 Stinger missiles on one side, two Hellfires on the other, with a 30 mm autocannon (and 12.7 mm machinegun) in between (Leonardo DRS)

- Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense (M-SHORAD), anti-aircraft and counter-drone weapons mounted on 8×8 Stryker armored vehicles;

- Two batteries of Israeli-made Iron Dome missile defense systems, as a congressionally-mandated stopgap version of the Indirect Fire Protection Capability (IFPC); and

- The Integrated Visual Augmentation System (IVAS), high-tech targeting/night vision goggles for foot troops.

There are no comparable roll-outs in 2022, but 2023 will see another five major fieldings:

- Next-Generation Squad Weapon (NSGW), in both assault rifle and squad automatic rifle variants, to replace the M4 and M249 SAW for every infantry squad;

Sandia National Laboratories glide vehicle, the ancestor of the new Army-built Common Hypersonic Glide Body

- Precision Strike Missile (PrSM), a lighter-weight but longer-ranged replacement for the ATACMS missile;

- Initial version of Enhanced Range Cannon Artillery (ERCA), doubling the range of the current M109 Paladin howitzer, shells will still be loaded by hand;

- The full-up, US-built version of IFPC, emphasizing defense against cruise missiles; and

- The first four-launcher battery of the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW).

Then the hits keep coming once a year:

- 2024: the full-up version of the ERCA howitzer, with an automatic loader (look ma, no hands!);

- 2025: the Future Tactical Unmanned Aerial System (FTUAS) to replace the Shadow drone;

- 2026: the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle (OMFV) to replace the M2 Bradley troop carrier.

(Note that if you counted both versions of IFPC separately, and both versions of ERCA, you end up with 12 major fieldings. We’re saying 10 because we consider those phases within the same program).

A little further out beyond the 2026 planning horizon, are two types of Future Vertical Lift aircraft, either high-speed helicopters or tiltrotors: the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA) to replace the OH-58 Kiowa scout and the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) to replace the UH-60 Black Hawk transport.

Given the track record of aviation programs, these may well be the most expensive of all.

President Reagan and Defense Secretary Weinberger

From Reagan To Night Court

This is a lot of new technology that has to move into production in relatively few years. Setting aside a slew of cancelled programs like the Future Combat System, the last time the Army successfully pulled off something on this scale is the Reagan-era Big Five. The UH-60 Black Hawk enters service in 1979, the M1 Abrams tank in 1980, and the M2 Bradley and the Patriot missile in 1981; the AH-64 Apache went into full production in 1982 but only entered service in 1986.

The Army prioritized the Big Five in the 1970s, stuck with them through the 1980s, and used them to great effect in the 1991 Gulf War. (The Patriot’s actual performance was criticized sharply by what is now the Government Accountability Office). And there were plenty of growing pains along the way, including chronic cost overruns.

The latest upgrade to the US Army M1 Abrams tank, with Trophy Active Protection Systems (APS) and improved protection for machinegun operator.

The Reagan administration plowed through those problems — in all four services, not just the Army — by massively increasing the Pentagon budget. That’s not looking like an option this time. The current Army plan assumes the service’s budget remains static, but Pasquarette thinks even that is optimistic.

“Our strategy right now assumes a topline that is fairly flat. I’m not sure that’s a good assumption,” he told the audience at AUSA. “So when the budget does go down – and we all know… someday it’s going to go down — will we have the nerve to make hard choices?”

“Even if we have a flat topline, our best scenario, we may need to have an appetite suppressant,” he went on. Today, the Army is trying to: slowly increase its total number of soldiers; fund all the training, equipment, and supplies required to “fight tonight“; and ramp up modernization for future wars. At some point, the service may have to sacrifice in one or two of those areas to protect the third.

Optimists might argue the Army can find the funding by cutting spending.

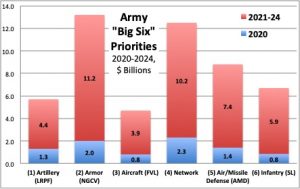

LRPF: Long-Range Precision Fires. NGCV: Next-Generation Combat Vehicle. FVL: Future Vertical Lift. AMD: Air & Missile Defense. SL: Soldier Lethality. SOURCE: US Army. (Click to expand)

In hours of grueling “night court” sessions going over the entire budget, the Army freed up $33 billion in its 2020-2024 plan, cutting or cancelling 186 lower-priority programs to fund the 31 top priorities. Undersecretary (and Secretary-designate) Ryan McCarthy has said a second round of reviews is finding another $10 billion in the draft plan for 2021-2025. The service will probably do a third round — but the savings will almost certainly be smaller, because the low-hanging fruit is all already gone.

“We’ve already taken a couple of pretty good, hard looks at the portfolio,” Pasquarette said. “If we take another, third one, I’m not sure there’s not enough efficiencies there… to fund what we see coming.”

So the Army will see diminishing returns from its internal reforms at the same time as the cost of modernization is rising — and it will rise as programs move into production, even if they’re managed perfectly.

“Will there be a decision by our leadership that… we need to stretch things out?” Pasquarette asked. “We haven’t gotten any guidance to do that yet. I think they’d have to be shown we can’t make ends meet” first.

President Trump with the future Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Mark Milley, and the future Defense Secretary, Mark Esper

Esper Won’t Save You

If the Army can’t find all the funding internally, will the Office of the Secretary of Defense come to the rescue, either by creating bigger budgets or by cutting the other services? The service’s proposed plan for 2021-2025 just went to OSD for review.

Some Army partisans may be optimistic because the new Defense Secretary, Mark Esper, and the incoming Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Mark Milley, led the charge for the current modernization plan when they ran the Army. But Esper and Milley will be under pressure to show they’re not captives of their former service. Our bet: They won’t overturn the modernization priorities they set, but they won’t bail the Army out of self-created problems, either.

Bruce Jette

That puts tremendous pressure on the Army to contain the costs of its new modernization programs.

What’s crucial, Pasquarette told me, is the tight alignment between the four-star chief of Futures Command, Gen. Murray, and the civilian chief of Army procurement, Assistant Secretary for Acquisition, Logistics, & Technology Bruce Jette. (By law, a Senate-confirmed civilian must have the final say). That’s an unprecedented partnership that just didn’t exist in the 1970s or ’80s, Pasquarette said, when future concepts and actual procurement were run by separate bureaucracies.

“That’s, I think, fundamentally different than what we’ve done in the past,” Lt. Gen. James Pasquarette, who builds the service’s five-year funding plan, told me and another reporter yesterday. For the first time, there’s a single four-star commander overseeing every stage of Army modernization, from early concepts to large-scale equipping.

Gen. John Murray, first chief of Army Futures Command, speaks at its formal activation in Austin.

At the same time, that four-star, Gen. Mike Murray, doesn’t have to worry about every single procurement program from boots to rations. He and the eight elite Cross Functional Teams (CFTs) that work for him concentrate on the Army’s top priorities. So, when I asked Murray at the recent Defense News conference what would be his key to success, his answer was immediate:

“Focus,” he said. “The Army has” — at last count — “692 programs of record. The CFTs have about 31. I say ‘about’ because some are not programs of record.” (At least, not yet. Some of the 31 are early software-development and experimentation efforts that may well grow into full-scale formal procurements). These 31 are grouped into six categories — artillery, armored vehicles, aircraft, networks, air & missile defense, and soldier equipment — known informally as the Big Six, a callback to the 1980s’ Big Five.

The top four Army leaders — the secretary, undersecretary, chief of staff, and vice-chief — are watching the 31 initiatives closely, Murray said: “Every week we sit with them and go through where we are with those programs.”

Army 30-Plus Priorities – R… by BreakingDefense on Scribd

But the Army’s not only doing things differently at the top. The other big innovation, Pasquarette said, is how the service is listening to regular soldiers. Each of the priority programs is being run through a series of “soldier touch points” where regular troops try out prototypes, often in real field conditions, and give immediate feedback to senior officers and industry engineers. For a new set of targeting/night-vision goggles being introduced this fall, for example, a battle-hardened 35-year-old sergeant served as senior technical advisor, and hundreds of infantry tested different versions.

Army Sergeant First Class Will Roth (foreground) and other soldiers check out the new ENVG-B night vision/targeting scope.

The Army’s also trying to listen to industry when it says new technology is not ready or is too expensive. The Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle program, for instance, made a hard call to rein in its requirements for armor protection based on industry feedback.

The goal of all this feedback is to refine the official requirements in the prototyping and experimentation phase, before the fateful move to the much more expensive production phase. It’s “to make sure what we go with as a requirement at the front end that is something we can realize and something we need,” Pasquarette said.

Getting things right up front — in the next few years — will help smooth out the Army’s ambitious ramp-up in the 2020s. The risk of failures along the way remains, however, very real.

Norway’s air defense priorities: Volume first, then long-range capabilities

“We need to increase spending in simple systems that we need a huge volume of that can, basically, counter very low-tech drones that could pose a threat,” Norway’s top officer told Breaking Defense, “so we don’t end up using the most sophisticated missile systems against something that is very cheap to buy.”