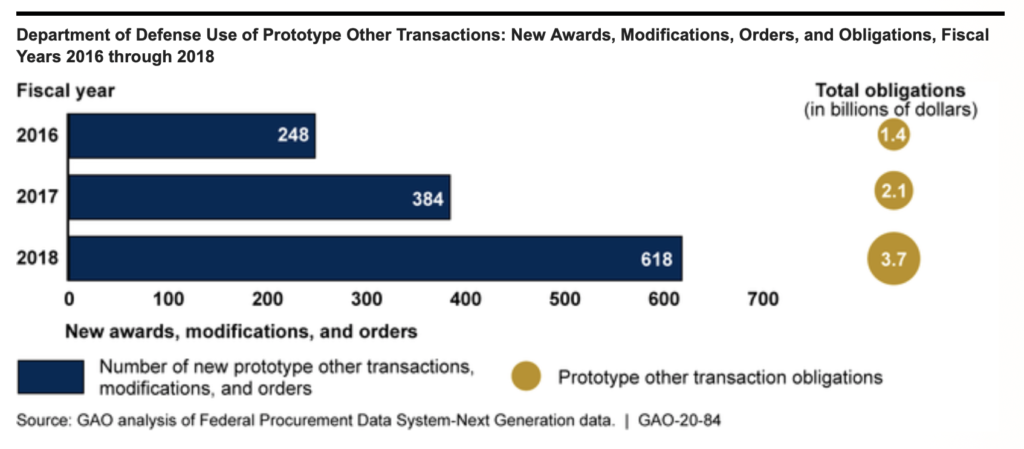

WASHINGTON: The Government Accountability Office has some rare good news on Pentagon procurement. Not only did the chronically critical congressional watchdog find no major flaws in how the Defense Department has been using Other Transactions Authority (OTA): GAO found that one of the most promising uses of OTA contracts, rapidly prototyping innovative technologies, had increased by a stunning 164 percent in just two years.

From 2016 to 2018, GAO reports, “obligations made on prototype other transactions nearly tripled from $1.4 billion to $3.7 billion.”

(“Obligations” refers to money the government commits itself to paying a specific party, which often occurs long after Congress has authorized and appropriated the funding. “Outlays” are money the government has actually spent.)

Will Roper

Pentagon reformers have embraced OTA contracting as a way to bypass the traditional bureaucracy that makes the Pentagon a difficult place to do business with — especially for the new, small, innovative companies whose technology the military wants but which lack the experience or overhead to handle the regulations. Will Roper, the head of Air Force acquisition, is the most prominent user and evangelist of OTA contracts, but the Navy and Army are also increasingly interested. Congress has passed several bouts of legislation to encourage the Pentagon to do more prototyping and to use a wider range of contracting techniques, all in order to buy weapons more quickly and close the gap between the pace of commercial innovation and the lumbering military.

It looks like OTAs are going to the kind of outside innovators that Congress intended:

“DoD data shows that companies that typically did not do business with DOD participated to a significant extent on 88 percent of the transactions awarded during this time,” GAO reports. “The Army awarded the most transactions; some of which were on the behalf of other DOD components that wanted to leverage transactions the Army previously awarded to meet their own components’ needs.”

So, the amount being spent on prototyping has more than doubled, and most of it’s going the right placs. That’s good. But is it good enough?

Bill Greenwalt

“Nothing Burger”?

I asked Bill Greenwalt, a longtime BD contributor, veteran SASC staffer, and former senior Pentagon official who helped write much of the legislation dealing with prototyping and other acquisition reform. He called the increase “kind of a nothing burger. Yes, it is progress, but not even close to what is necessary to bring in non-traditional innovation to compete with the Chinese.”

Why? Because while the spending has increased, it is still much smaller than, say, how much money is spent by Pentagon officials using the government purchasing card. Part of the reason this spending is still pretty tiny — by Pentagon standards — is that very little, if any, is being spent to procure and mass-produce technology, as opposed to funding handfuls of prototypes.

“That’s really the big new factor in all this: whether they will move from prototypes to larger contracts to buy a weapon system once the prototypes prove out,” Greenwalt notes. “Will it be a regular contract or an OTA?”

That’s unclear from looking at this report. Widespread use of OTAs is relatively new, which means it’s pretty early for OTA programs to have gone beyond the prototyping stage. Indeed, there have been few new major programs in the last decade, especially in the Army. But now the largest service is ramping up an ambitious modernization effort that will move 31 priority programs from prototype to production in the next decade.

Greenwalt believes the Army contract officers at Picatinny Arsenal, who write most of the OTA contracts, are still attaching too many requirements from the Federal Acquisition Regulations (the infamous FAR). He says should trim the prototype contracts so they can issue them even more quickly. The obstacle, he argues, is a persistent reluctance among military contract officers to embrace OTA on a broad basis and to jettison decades of training and bureaucratic tradition, even in the face of broad congressional support and pressure from senior officials like Roper.

Once the prototypes being funded now make it to the stage where DARPA or a service has to award a production contract, that’ll give both policymakers and Congress a much clearer picture as to just how much the acquisition bureaucracy can embrace and effect change.

EUCOM asks for $83 million for air base defense in FY25 unfunded wish list

The air base defense priority is the largest of the three items EUCOM listed, with almost $67 million needed for additional sensors that would plug into the Air Force’s base defense network.