The prototype M1299 armoured howitzer test-firing at Yuma Proving Ground on March 6, 2020.

WASHINGTON: As the Army urgently rebuilds its long-neglected artillery branch, it’s test-firing some impressive hardware in the southwestern desert and over the Pacific. But all those technologies, the Army’s artillery modernization director told me, are in service to a single purpose:

Then-Col. John Rafferty teaches field artillery operations in Tajikistan.

After decades of depending on air support, the Army needs its own long-range precision firepower to blow holes in high-tech defenses so US aircraft, warships, and ground troops can pour through.

No one wonder weapon can solve this problem on its own, Brig. Gen. John Rafferty told me in an interview ahead of this week’s successful Precision Strike Missile test. Instead, it requires a complete toolkit of complementary weapons with overlapping ranges, each optimized for a different set of targets at a different level of the future fight.

The Portfolio’s Progress

“Our analysis has been focused on how we’ll fight with these things,” Rafferty told me,” how they complement one another to take down the A2/AD [Anti-Access/Area Denial] complex to open those windows of opportunity for the joint force.”

“At the tactical level, that’s ERCA,” he said. Extended Range Cannon Artillery is an upgraded Paladin armored howitzer with an extra-long barrel, supercharged propellant and advanced ammunition that hit targets over 40 miles away in a recent test. Originally, the Army had focused on the new rocket-boosted XM1113 shell, but the March test proved it was possible to tweak the existing precision-guided Excalibur to reach similar ranges, Rafferty told me. He doesn’t see the two rounds as redundant, however. Excalibur will offer precision, the XM1113 wide-area suppression.

Lockheed’s prototype Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) fires from an Army HIMARS launcher truck in its first flight test, December 2019.

“For theater opening, that’s PrSM, knocking down some of the sophisticated air defense or maritime targets,” Rafferty said. The Precision Strike Missile has proven its ability to hit targets as close as 53 miles in last week’s test. (Short-range shots are actually harder because the sudden deceleration stresses the missile). The prototype should max out in long-range-shots next year at over 300, but a future upgrade could fly over 400. PrSM is sleeker, longer-ranged, and smaller than the Reagan-era ATACMS it replaces, yet hits with the same force thanks to more advanced explosives.

“At the strategic level, that’s strategic fires opening the door for the joint force,” he said:

The high-cost, high-performance option here is the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, a rocket-powered boost-glide missile that was test-fired in March for the first time in three years. The expected range is classified but could easily be thousands of miles.

Hypersonics are so cutting-edge – and correspondingly expensive – that they’re being developed by a special Army organization, Lt. Gen. Neil Thurgood’s Rapid Capability & Critical Technologies Office, as part of a joint effort with the Navy. Rafferty’s Long-Range Precision Fires Cross Functional Team will take over the program as it moves from prototype to production, and it’s already working out training and tactics.

The hypersonic missile set to enter service in 2023, Rafferty said, will probably be an “exquisite” weapon that must be reserved for the hardest and most critical targets. So, to barrage larger numbers of softer targets, Rafferty’s team is developing the Strategic Long-Range Cannon, a supergun using gunpowder to launch guided projectiles over one thousand miles. While a full-up SLRC prototype won’t be test-fired until 2023, two “test assets” are already launching simulated projectiles called slugs.

“There are skeptics,” Rafferty admits. “But every time we get a chance to engage the skeptics with our technical experts, they generally walk away thinking, ‘that could work.’ And if it does, then it’s a capability we ought to have in the Army.”

In this big picture, even a thousand-mile supergun is just one more useful tool in the toolkit, and no one tool is irreplaceable. Rafferty’s boss, Army Futures Command chief Gen. John Murray, has even said: “If the Strategic Long-Range Cannon does not deliver, we have hypersonics.”

But how do all these different weapons add up to more than the sum of their parts?

Many Weapons, One Mission

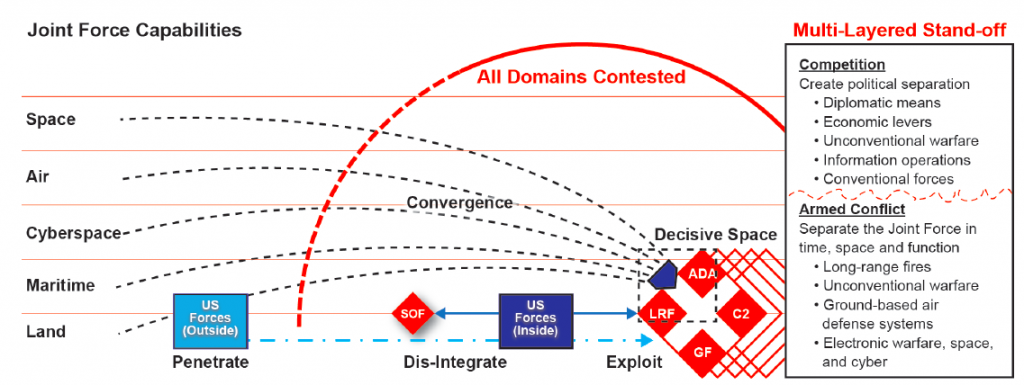

“How it’s all linked together: It starts with the operational concept,” Rafferty said. “When you look at Multi-Domain Operations” – the Army’s concept for future conflict – “and then what I think will emerge as a joint operational concept by the end of the year” – what the Pentagon’s calling Joint All-Domain Operations – “the fundamental problem is layered enemy standoff.”

SOURCE: Army Multi-Domain Operations Concept, December 2018.

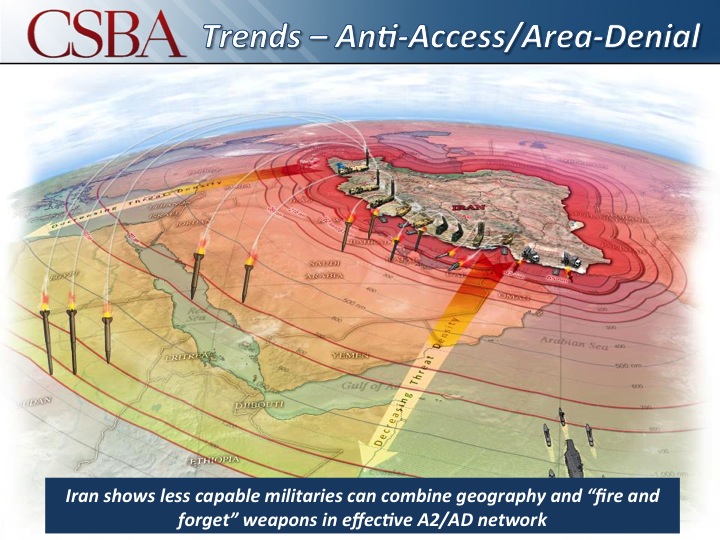

Great power competitors like China and Russia, and even regional threats like North Korea and Iran, are painfully aware of how American airpower reigned unchecked over Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Serbia. So they’ve invested heavily in the kind of long-range, precision-guided weapons that were once an American monopoly. The resulting Anti-Access/Area Denial defenses combine surface-to-air missiles to keep out US aircraft; surface-to-surface weapons to hit airbases, aircraft carriers, and ground forces; radars, drones, and satellites to detect and target the Americans at a distance; plus supporting forces from fighter jets to submarines to mines.

Reach of Iranian weapons systems (CSBA graphic)

With adversaries investing so heavily in countering US airpower, Rafferty said, “it really then has to be surface-to-surface fires that begin to reduce the enemy integrated air defenses and long-range artillery that make up that layered standoff of A2/AD.” That means the Army has to switch from being a consumer of the other services’ long-range fire support to a provider of long-range firepower to support the other services.

The problem is the Army largely neglected its artillery for the last three decades, just as it neglected other essentials of large-scale conventional conflict such as anti-aircraft defense and electronic warfare. Now it’s scrambling to rebuild all three, with artillery taking pride of place.

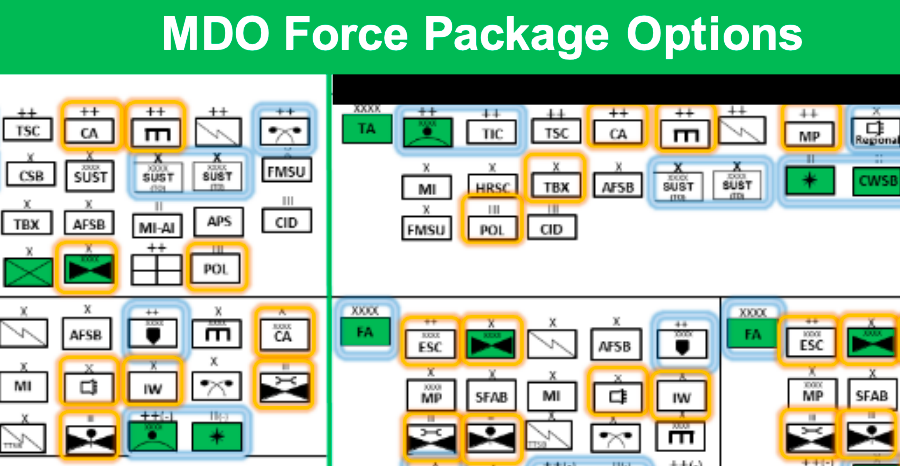

“Think about the experimentation with Multi-Domain Task Forces,” Rafferty told me. Starting with an experimental unit in the Pacific, he said, “the pilots were successful enough in showing what could be done, centered around a field artillery brigade as the headquarters, with additional intelligence, cyber, and electronic warfare capability.

“The Army is committed to Multi-Domain Task Forces beyond just the initial pilot,” he went on, with a second MDTF being stood up in the Pacific and a third in Europe. To coordinate long-range firepower at a higher level, he said, “we’re developing the Theater Fires Command. That will give us the ability to employ strategic fires at a theater level and integrate coalition partners.”

Part of the Army’s early draft for new Multi-Domain formations. Green: existing units to receive new equipment. Blue: new units to be created. Orange: units currently in the National Guard or Reserve that might move to the regular active-duty force.

Why are these new formations necessary? “We’re not structured now to fight and win with the systems that we’re going to deliver in the not too distant future,” Rafferty said bluntly. The Army will need new organizations, new tactics, and new training to make the most of the new hardware.

That’s why Rafferty’s Cross Functional Team, while it has representatives from all across the Army, is based at Fort Sill, the intellectual home of the artillery. “Here at Fort Sill,” he told me, “we can make sure that our doctrine is right and the training base is established so we’ve got artillerymen ready to man the systems.”

“Early in the morning when I go out and do PT, I see privates who are just getting started with their Army careers, and you have officers here for the basic and the advanced courses, and non-commissioned officers that are back here for professional military education,” Rafferty told me. “And you realize that you’re looking at the future hypersonic section chief, or a first sergeant of an ERCA battery, or the battery commander firing the first PrSM missile.”

“It does keep you pretty well grounded,” he said. “You realize that this is real and that these soldiers are counting on us to deliver.”