ABMS construct

How important do members of the Air Force think the nascent Advanced Battle Management System will be to their service and to the entire US military? Three officers have take to our pages for second time to write about the best path forward for the system, this time in light of a sharply critical report by the Government Accountability Office. Let their words speak for them. Read on! The Editor.

The quest for a weapon system allowing the “rapid collection and distribution of information and intelligence regarding the movements of friendly and hostile” began with Report 118A, “Continental Air Menace: Anti-Aircraft Defence,” filed by the Royal Air Force in Great Britain nearly a century ago, May 1923.

The report was forged in the midst of a fierce debate over whether fighters or bombers would be the best means of countering German air attacks, It captured a recognition that weapon platforms alone were of little value unless they could share information with other platforms. In typical bureaucratic fashion, 118A recommended the formation of a subcommittee, one focused on studying how best to connect aircraft, defense artillery, and intelligence personnel. With that recommendation, the modern quest to unite warfighting domains had begun.

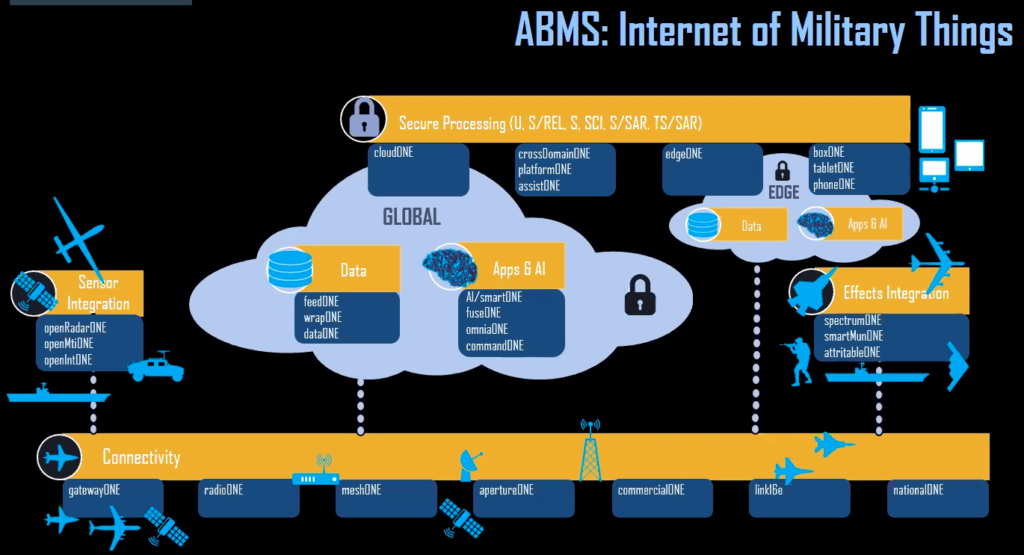

The latest effort in that quest, the Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS), took something of a body blow recently when the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report criticizing how the Air Force was handling the early stages of the system’s development. The report critiqued the Air Force on two levels. On the first level, the GAO said that the Air Force should submit the documentation that typically accompanies big acquisitions programs, things like cost and schedule estimates (and the Air Force has said that it will). On a deeper level, the GAO indirectly suggested that ABMS’s architects’ do not have a clear path forward to bring it from where it is today—an ambitious and closely-guarded idea—to a system enjoying widespread Joint force adoption.

Unless all five services adopt ABMS it will do little good for the Joint force, no matter how technologically advanced the system is. In building the system, the Air Force faces a basic choice between placing the weight of effort on the top, beginning at the strategic level and working down, or the inverse, beginning at the tactical level and building up. ABMS is more likely to be adopted if our service builds the system from the bottom-up.

Unless all five services adopt ABMS it will do little good for the Joint force, no matter how technologically advanced the system is. In building the system, the Air Force faces a basic choice between placing the weight of effort on the top, beginning at the strategic level and working down, or the inverse, beginning at the tactical level and building up. ABMS is more likely to be adopted if our service builds the system from the bottom-up.

What “Build Bottom-up” Does, And Does Not, Mean

When we say “build bottom-up,” we mean that this process of iterative experimentation should occur at the tactical level. The end users of ABMS—Joint sensors and shooters—should be the ones cycling through the new techniques and technologies that will come to form ABMS. Speaking for our own community of Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) Airmen, this would mean creating and funding innovation centers within existing TACP squadrons, units which are already collocated with the Army and focus on tactical command and control.

Building bottom-up does not mean that the Air Force should abandon centralized requirements, allowing free-for-all acquisitions in the hopes that the resulting medley of systems will somehow and someday be able to talk to each other. This has been the status quo approach and it has left the different services, and even different platforms within the same service, disconnected from each other.

Building bottom-up also does not mean that the DoD should ignore the importance of sound strategy or the skillful pairing of strategic ends with operational means. The justification for building bottom-up is based on the virtues of building from the tactical level, not on any importance inhering in that level during the planning or execution of military operations.

A Bottom-up Build Paves the Way for Widespread Adoption

The advantages of building bottom-up come from the checks and balances that such an approach would place on the scope and systematic complexity of future ABMS development. As with any good system of checks and balances, a bottom-up build anticipates counterproductive yet alluring impulses, and then relies on systemic solutions rather than any one person’s good judgment. Put in layman’s terms: a solid field test can kill the good-idea fairy before the fairy establishes hardened bunkers in the program’s budget and then blows it up with the cost overruns that are all too common in major defense programs.

One of the GAO report’s principal concerns was that, without firm requirements, there is no way to know whether ABMS will meet the needs of actual warfighters. Their fear is that ABMS will need dramatic requirements changes as its components make the leap from prototype to the field, and that these requirements changes will lead to dramatic cost growth. A bottom-up build requiring tactical end-users to perform experiments in the first place, would provide a check on this type of requirements change. This brings us to the good-idea fairy’s converse—but still positive—outcome for the layman: some early testing can reveal those things which must be addressed in the system lest they be dismissed by hand-waving over the drawing board during discussion of more lofty outcomes. The baseline features that do not work are equally likely to run the cost train off its track; witness the F-35 and KC-46 for contemporary examples.

Another counterproductive impulse is the tendency towards secrecy, which was in fact the Air Force’s first defense against the GAO report, saying that the analysts did not have access to classified information needed to fairly adjudicate ABMS progress. While Air Force leaders likely have a point—GAO does not have the full story— the fact that ABMS is so locked up behind classification is part of the problem. The more inaccessible the system, the less attractive it will seem in comparison to legacy technology that is easier to access. An old push-to-talk radio at an operator’s fingertips will seem more appealing than a new C2 system locked behind multiple vault doors. Experimentation at the tactical level, where operators are less likely than senior Pentagon officials to have access to special programs, would make plain the trade-off between security and usability, forcing hard looks at what absolutely must be classified.

A final counter-productive impulse is the tendency towards service-centrism. The modus vivendi in Washington is to break programs apart so that services can have more control and in turn more budgetary influence. One way of checking this impulse is to move development away from the Pentagon and out to the tactical level, where the only imperative is to survive and defeat the enemy.

Widespread Adoption is the Whole Game

The importance of widespread adoption is baked into ABMS’s founding concept. The Air Force intends ABMS to be the technical backbone of Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2), a new command and control philosophy emphasizing decision speed across all the domains—the Air Force in fact defines JADC2 as “the art and science of decision making… [in order to act] faster than an opponent.” Widespread adoption is fundamental because, as long as people (rather than machines) are responsible for choices about life and death, deciding fast will require the widespread diffusion of decision authority. The only way to make a lot of life-and-death choices fast is to have a lot of people making those choices. If only a few central decision makers can access ABMS, decisions will bottleneck and ABMS will fail JADC2.

More generally, a central finding from the empirical study of military innovation is that new military technologies do not by themselves change the balance of military power. It is instead the widespread adoption and integration of new military technologies that shifts the balance of power. It is only when “a round technological peg” fits into a round doctrinal and operational hole that militaries become more powerful. (Eds note: this is a core tenet of the Revolution in Military Affairs and its cousin, transformation.)

No matter the technological promise of ABMS, if the average tactical operator does not think it serves his goals, or he never sees it in the first place because the system has been placed behind a firewall of classification, the impact of ABMS on the military’s ability to coerce or defeat peer adversaries will be null.

Conclusion: The Lesson of Report 118A

Fifteen years after the Royal Air Force (RAF) filed Report 118A, the RAF began to integrate radar into its air defense operations. Radar would eventually become known as one of the most important peacetime innovations in military history, one that helped Great Britain temper the power of the German Luftwaffe in World War II.

A cursory reading of radar as a test case would suggest that it was the story of a new piece of technology that a few high-ranking individuals recognized as transformative and forced into use. This misses the point that radar would not have happened as fast, and may not have happened at all, had the RAF as a whole not been in a position to adopt it. Report 118A set in motion a chain of events that made the RAF—the entire force, at every level—eager and able to integrate anything that helped them better understand the location of friendlies and hostiles.

The lesson of 118A is that, if ABMS wishes to succeed, it needs to be built in a way that prepares the Joint force for its eventual adoption. With a balanced approach that includes “bottom-up” design and testing, we can ensure its success.

Paul Birch, an Air Force is a colonel in the U.S. Air Force. He is the commander of the 93rd Air Ground Operations Wing, which contains the preponderance of forces responsible for providing the Army and Air Force with tactical-level command and control. He holds a PhD in Military Strategy from Air University. LinkedIn.

Ray Reeves, an Air Force captain, is a Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) officer and Joint Terminal Attack Controller (JTAC) at the 13th Air Support Operations Squadron at Fort Carson. He is a doctoral student in organizational leadership at Indiana Wesleyan University. .

Brad DeWees, an Air Force major, is a TACP and JTAC at the 13th Air Support Operations Squadron at Fort Carson. He holds a PhD in decision science from Harvard University.

The views expressed in this article are the authors’ alone and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. government.

Lockheed wins competition to build next-gen interceptor

The Missile Defense Agency recently accelerated plans to pick a winning vendor, a decision previously planned for next year.