A soldier from the Army’s offensive cyber brigade during an exercise at Fort Lewis, Washington.

WASHINGTON: A low-key Army project known as Rainmaker is quietly developing common standards to let combat networks share data for everything from targeting smart weapons to training AIs.

The technology was developed by the Army’s C5ISR Center at Aberdeen Proving Ground and field-tested this fall on the sidelines of the Army’s Project Convergence wargames. Two contractors, Palantir and General Dynamics, are now helping develop full-up prototypes. The Army aims to start fielding an early version of Rainmaker to its combat brigades in 2023 and hopes to share it with the other services and foreign allies as well.

It’s unglamorous but essential work. All too often, in command posts around the world, the easiest way to get data from one system to another is still to scrawl it on a sticky note. That technique doesn’t scale up all that well to the masses of detailed data required to coordinate complex combat operations.

Even when today’s systems are nominally capable of communicating, they often can’t send full, detailed reports, just summaries and other metadata, pared down to fit in low-bandwidth messaging formats created in the 1990s. For the recipient, that’s a lot like getting all your news from the headlines in your Facebook feed, without ever actually clicking on an article.

“Those standards are limited in terms of how much information we can put in there,” said Upesh Patel, a senior engineer at the C5ISR Center. “You can easily put ‘a tank’ into a targeting message [today, but] what we did with Rainmaker is we were able to add … ‘Hey, look, this is a tank, and it has active protection countermeasures, or it’s up-armored, or it has X, Y, and Z capabilities.’ That information is critical to the weapons systems that we use to target those systems.”

An experimental Army robot, nicknamed Origin, at the Project Convergence exercise at Yuma Proving Ground, Ariz.

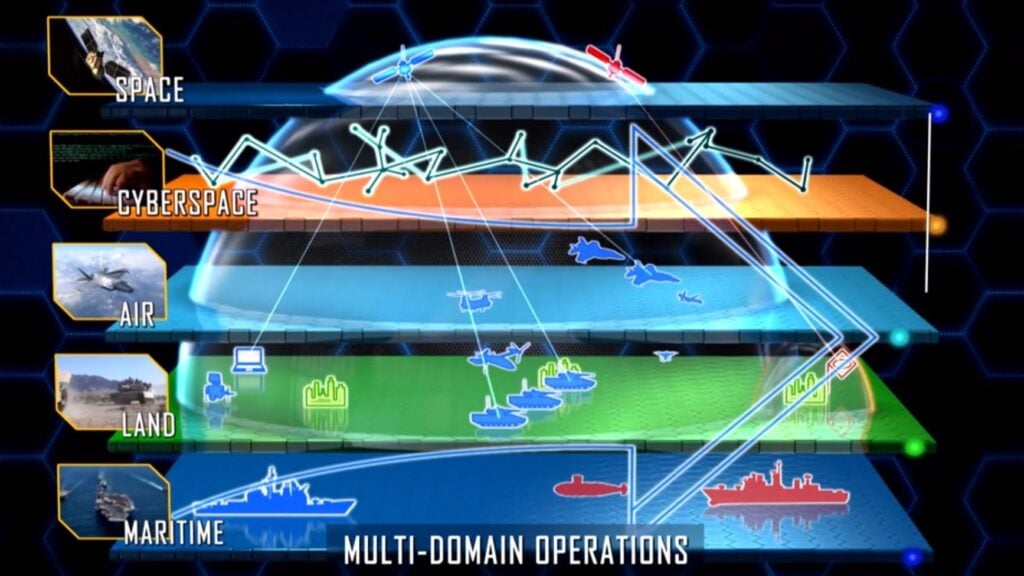

If you can’t share that kind of detailed data – a lot of it, and fast – then you can’t swiftly unleash salvos of precision-guided weapons or train machine-learning algorithms to automate staff work and advise commanders. You can’t realize the Pentagon’s grand vision of a mega-network linking friendly forces across land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace, called Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2).

For the first-ever Project Convergence exercise this year, Army Futures Command kludged together a good-enough network to pass precision targeting data from Intelligence Community satellites and Marine Corps F-35s to Army aircraft, artillery and ground vehicles. But that was a limited, one-off solution linking small numbers of selected systems.

The military is still far away from the JADC2 vision of linking “every sensor” to “any shooter.” “That’s aspirational,” said Maj. Gen. Peter Gallagher, network modernization director at Army Futures Command. “Unless you get the underpinnings of a foundational data fabric, it will never happen.”

A soldier and a civilian work on the Advanced Field Artillery Tactical Data System. The initial version of AFATDS was fielded in 1981.

Rainmaker’s Evolution

What is a data fabric, anyway? When I asked the Army, Gallagher and some of his leading technical experts called me to explain. In essence, a data fabric is a set of common technical standards and APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) that enable otherwise incompatible systems to share data.

Maj. Gen. Peter Gallagher

That means sharing all their data, not just summaries and other metadata that lack the nitty-gritty detail required to feed AI algorithms or target precision weapons. It means sharing data directly and automatically from machine to machine, without a human having to manually reenter data – a time-consuming and error-prone process. It means sharing data with users holding different levels of security clearances, allowing lesser credentials to access less sensitive data rather than locking them out of entire databases. It means sharing data all the way from satellites and central databases to individual aircraft, vehicles and frontline troops – and the Army has thousands more such low-bandwidth “edge users” than any other service.

“Everybody, every decision-maker on [every] echelon, we want [to] give them the data they need to make the decisions they need, at speed,” Gallagher told me, “all the way down to that that infantry squad.”

That’s not how it works today. Even within the Army, there are multiple systems – some for logistics, some for artillery, some for aviation, and so on and on and on – that share data only grudgingly. These legacy systems require extensive custom tailoring and troubleshooting to connect to any new technology.

Over the years, “I went out to numerous NIE [Network Integration Evaluation] exercises and I saw all the pain points that soldiers were going through [and vendors] struggling to integrate their capability into the existing Army infrastructure,” engineer Patel told me. “It wasn’t the vendors’ fault, it’s just how the Army systems were designed.”

With Rainmaker, he said, “we wanted to provide a mechanism… to seamlessly pull and push information without having to go through all these transformations and translations.”

Army soldiers and contractors at a 2013 Network Integration Evaluation (NIE) exercise

The first incarnation of Rainmaker was a CONEX container full of computers, a cloud computing hub you could deploy to a war zone. Rainmaker got into the data fabric business with seed money from the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence, which was working on a Common Data Fabric for intel. But the Army’s C5ISR Center found itself tackling the most challenging piece of the problem: moving masses of data swiftly to forward command posts and frontline units with limited bandwidth and erratic connections.

“We basically started focusing more on the tactical aspects,” said Patel. The Intelligence Community often focuses on reports for generals, admirals, and high-level headquarters. But as part of the Project Convergence exercises this fall, a Rainmaker proof-of-concept passed detailed targeting data from a simulated brigade Tactical Operations Center at Fort Lewis, Wash. to a battalion TOC at Yuma Proving Ground, Ariz.

Now, in the inaugural Project Convergence held this fall, the Rainmaker data wasn’t used to target live weapons, Gallagher emphasized; that was handled by other systems. “Next year,” he said, “it will be fully incorporated into Project Convergence 21.”

To plan beyond that test, Gallagher’s Network Cross Functional Team is already working with Army procurement organizations, the Program Executive Officers for Command, Control, & Communications – Tactical (PEO-C3T) and the PEO for Intelligence, Electronic Warfare & Sensors (PEO-IEWS). The service plans to roll out network upgrade packages every two years, starting with Capability Set 2021 next year. Rainmaker won’t be ready for operational units then, but the plan is to include at least a “1.0” version in the next round in 2023.

“We’re actually comparing the work that the C5ISR center has been doing with Rainmaker with a couple of other vendor solutions,” Gallagher said. The Army called for white papers and then held a “Shark Tank”-style pitch day before awarding Palantir and General Dynamics Mission Systems (GDMS) Other Transaction Authority contracts, worth about $2 million each, to develop prototype data fabrics. If either or both prototypes prove promising, the Army can then fund field experiments with actual soldiers.

“Rainmaker’s really exploring commercial technologies, because there is a lot in industry in terms of [developing] common data fabric,” said Gallagher’s chief data officer, Portia Crowe. “Rainmaker takes the unique solutions that we need within the Army and couples that with a commercial solution.”

Multi-Domain Operations, or All Domain Operations, envisions a new collaboration across land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace (Army graphic)

Commercial, Joint, & Coalition

Using widely available commercial technology, rather than developing bespoke systems exclusively for the Army, should make it easier to find common technical ground with the other services and foreign allies.

“In terms of JADC2 and working with our joint partners, especially with what we’re doing with the Air Force right now, [we’re] looking at how do we utilize the common data fabric across the services,” Crowe said.

Joint data sharing – that is, between the US services – will be a major focus for Project Convergence 2021. Then Convergence 2022 will bring in forces from Britain, Australia and potentially other allies.

An annotated screenshot from the Army’s logistics software, GCSS-A (Global Combat Support System-Army)

“We have struggled, in the past, with trying to share information with our coalition partners, just because [of] the way the data is managed…transmitted and received,” said Alan Hansen, head of intelligence systems processing at the C5ISR Center. (He’s Patel’s boss). The data fabric will include “cell-based security”: Whereas current systems often deny a given user access to an entire file if they’re not authorized to see everything in it, Rainmaker will intelligently redact the report and only block them from seeing the specific pieces of data (or cells) that they’re not cleared for.

The Rainmaker data fabric doesn’t just bridge the gap between the Army, the other services, and US allies: It also bridges the gap between past and future. It’ll take decades to replace all the Army’s existing electronics with new technologies that are built to be compatible from the start. So as the service fields new systems, it’ll rely on Rainmaker to let them talk to the old ones.

“The systems that have been there around, they’re going to be around for another 10 years, let’s say,” Hansen told me. “But at the same time, we, the Army, have to grow into the next generation, [and] Rainmaker…allows us to bridge legacy with next generation.”

That next generation will include artificial intelligence that can’t run properly on the current, limited stream of data. The Rainmaker data fabric will be the foundation on which the Army – and others – can build a wide array of AI services.

On the intelligence side, Hansen said, “I’ve got to collect data, I’ve got to fuse the data, I’ve got to administrate the data, I have to then maybe package it up for targeting purposes and then send it over to a targeteers.” Once Rainmaker’s in place, he told me, “I [can] come up with a really slick new, next-generation analytics tools and capabilities that we can give to the warfighter.”