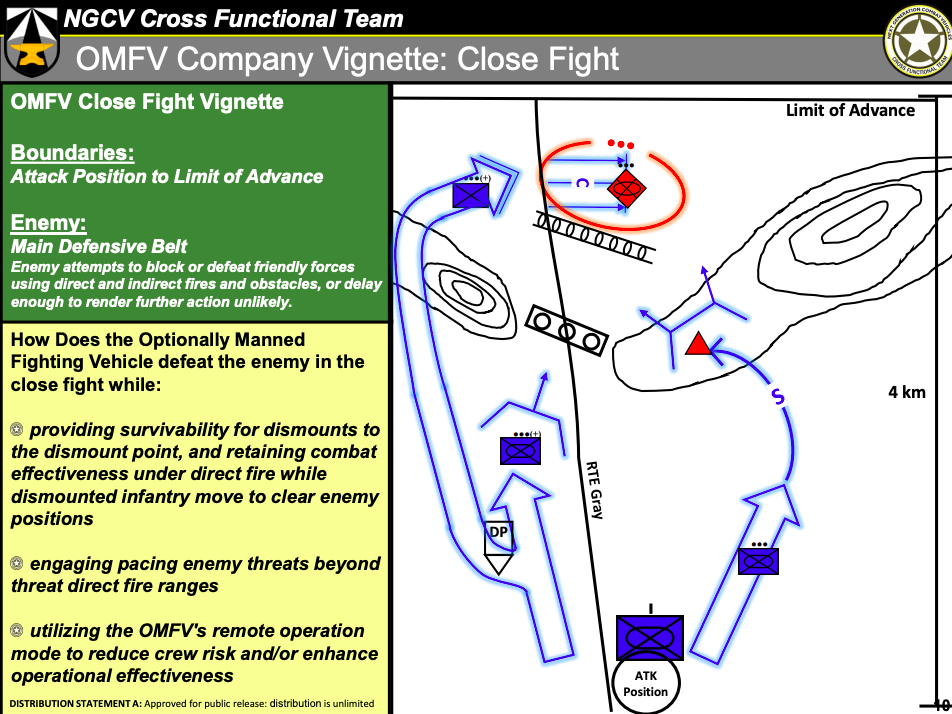

Army concept for how its future Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle will penetrate enemy lines.

WASHINGTON: The Army is taking industry concerns to heart as it revises its next Request For Proposals for a new Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle, officials told company representatives at an industry day on Wednesday.

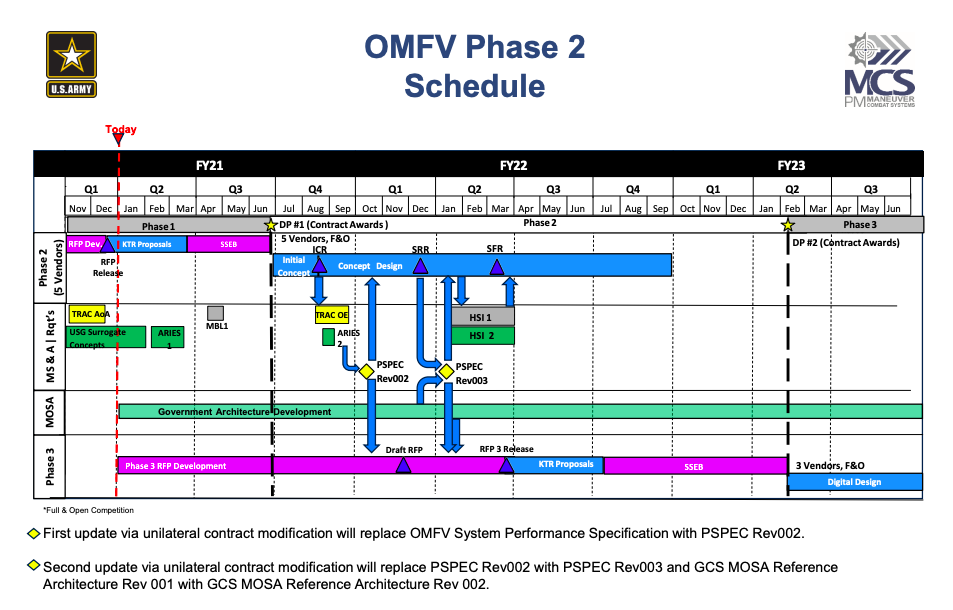

In particular, they’ve slashed the (virtual) paperwork required for the next phase of the program, Phase II, by more than 80 percent, and they’ve replaced a grueling Preliminary Design Review with a less demanding Systems Functional Review, which requires less detailed data and allows less mature technology. That change effectively defers some design and development work from the upcoming Phase II contracts, which run from roughly June 2021 through Sept. 30, 2022, to the later Phase III contracts, to be awarded in February 2023.

But there’s one big wrinkle they’re still trying to iron out: that four-month gap between the end of Phase II and the beginning of Phase III. From Oc. 1st, 2022 (the first day of the federal fiscal year) until early February 2023, the flow of funding from the Army to its contractors will pause. That could interrupt work on OMFV and force firms to furlough engineering teams.

Rheinmetall Lynx, a candidate for the Army’s OMFV

Now, a four-month gap in government funding is still a huge improvement over the Army’s original plan for OMFV. Back in March 2019, the Army issued an RFP that required would-be competitors to build a complete prototype vehicle at their own expense – with zero government funding – and deliver it for testing by Oct. 1st. Only one company, General Dynamics, managed to meet that deadline, and their vehicle didn’t meet the technical requirements. Afterward, the Army realized their schedule and tech specs were just too ambitious for industry to meet, so they rebooted the program with a longer timeline, drafting broad “characteristics” instead of rigid requirements, and the promise of government funding, not only to build the prototypes but to design them.

The rebooted program is now in what’s called Phase I, the period before the Army actually awards any contracts, when it’s fervently seeking industry feedback on how to structure the program.

Later this month – the target date is one week from today, Dec. 18 – the Army will issue the final, formal Request For Proposals for Phase II, what it calls “concept design.” Companies’ proposals are due in March, with the Army awarding up to five contracts in June. Each winner will get $61 million to develop its concepts and refine them through multiple rounds of back-and-forth feedback with the Army, using detailed digital models and simulations to explore different design choices and see what is most likely to perform.

Meanwhile the Army will use industry’s input to create more formal requirements and technical performance specifications. (It won’t actually lock these down until later in the program, to give industry maximum leeway to innovate). In January, the Army will also create a new public-private consortium of interested companies and universities, which will develop a Modular Open Systems Architecture (MOSA) for OMFV and other future vehicles, replacing the current VICTORY standards. The idea is to create a common set of technical standards and interfaces that all competitors will abide by, along the Army to mix-and-match components from different companies, install the same components on different vehicles, and easily plug-and-play upgrades as new tech becomes available.

The Army’s current schedule for the next few years of the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle program.

Mind The Gap

Once the companies have completed their Phase II concept designs, they’ll submit them to an Army Source Selection Evaluation Board. The SSEB will evaluate those concepts and pick up to three competitors to proceed to Phase III, with government funding to finalize their designs. All the Phase III competitors will proceed to Phase IV, when they’ll each build 12 physical prototypes for government testing. In late 2027, the government will pick the final winner and start Phase V, production, with the goal of fielding the first operational OMFV battalion in 2029.

The hiccup in this schedule is between Phases II and III. Remember, not every company in Phase II is guaranteed to make it to Phase III. (Again, the tentative plan is to narrow down from five vendors in Phase II to three in Phase III, though those exact numbers could change). They have to finish their concept designs and turn them in so the Army can evaluate them and pick the winners.

But what do the competitors do while they’re waiting for the Army to make its choice? The Army doesn’t want to pay them all to keep working on their designs for Phase III, because not all of them are going to make it to Phase III. But the Army doesn’t want the companies laying off their OMFV teams or reassigning them to other projects, either, because then the companies that do win Phase III awards will have a harder time getting work going again.

The Army is working on ways to square this circle, officials pledged. The four-month gap in the current schedule is a lot shorter than what the program faced in an earlier draft of the plan, and the service is hoping to make it even shorter.

They’re not yet ready to share details of how, which left some industry people I spoke to uneasy. But given the Army’s unhappy history of cancelled weapons programs – including multiple failed attempts to replace the Reagan-era M2 Bradley – it’s impressive progress that they’re being as open with industry as they are.

Norway’s air defense priorities: Volume first, then long-range capabilities

“We need to increase spending in simple systems that we need a huge volume of that can, basically, counter very low-tech drones that could pose a threat,” Norway’s top officer told Breaking Defense, “so we don’t end up using the most sophisticated missile systems against something that is very cheap to buy.”