US Army M1 Abrams tank with Trophy Active Protection Systems (APS) and improved protection for machinegun operator.

WASHINGTON: Between now and 2023, the Army will test new defenses against anti-tank missiles on a wider range of armored vehicles than ever before, from the massive M1 Abrams main battle tank to the lightly armored 8×8 Stryker.

A newly announced contract with Lockheed Martin also includes testing of what’s called the Modular Active Protection System (MAPS) “base kit” on two middle-weight war machines. One is the heavily armed M2 Bradley troop carrier; the other is the Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), basically a turretless utility variant of the Bradley.

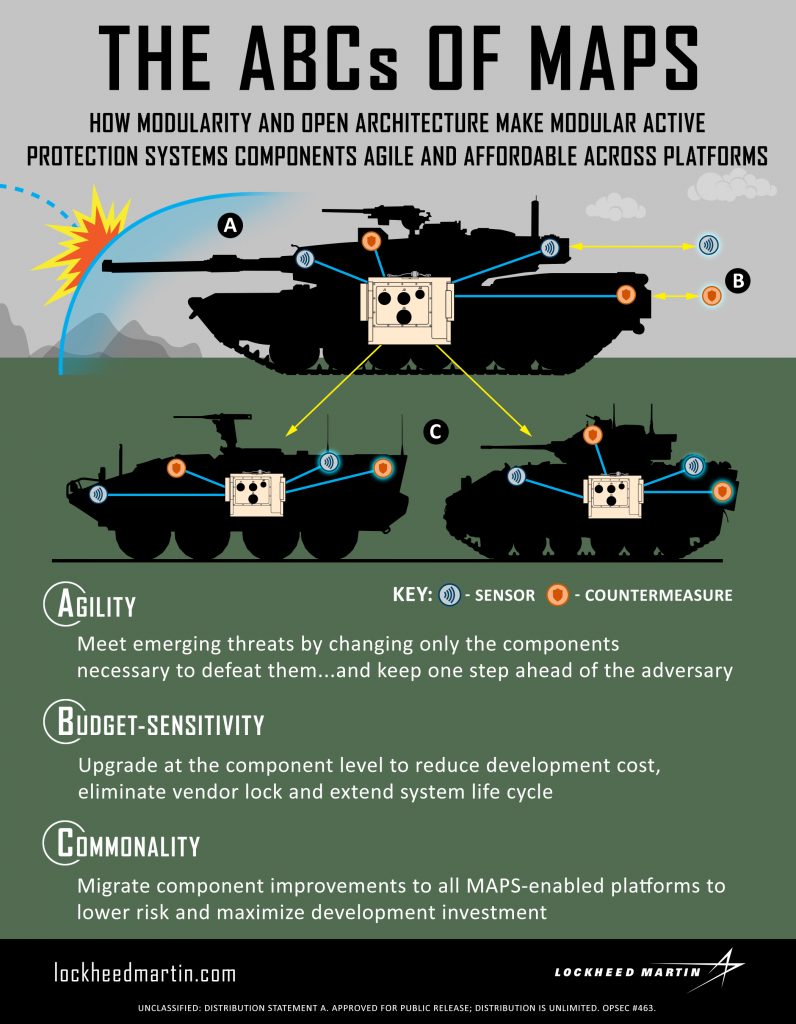

Lockheed Martin graphic

The Army and Lockheed have already used the Bradley extensively for earlier development and testing of MAPS, including live-fire tests with anti-tank rockets and missiles in 2019. But Lockheed has only done preliminary work with MAPS on Stryker, the company’s program manager, David Rohall, said in an interview. So the new contract will be the first integration and formal testing of the MAPS base kit on Stryker, Abrams, and AMPV.

Why does this matter? The Army is exploring a plethora of anti-missile defenses for its armored vehicles. Many Abrams tanks already have the Rafael Trophy, a battle-tested Israeli countermeasure which physically shoots down incoming anti-tank rockets and missiles. The Army has also been working to integrate another off-the-shelf Israeli active protection system, Elbit’s Iron Fist, onto the M2 Bradley, albeit with mixed success and delays. Bradley’s a smaller vehicle than Abrams with less room and electrical power to add radar-controlled interceptors. And the service is trying out two slimmed-down systems, one by Rafael and one by Germany’s Rheinmetall, on the Stryker. As the lightest of the vehicles in question, it has proven the hardest to protect.

Iron Fist-Light Active Protection System installed on a US Army M2 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle. (Rada photo)

So the Army has plenty of irons in the fire – but that’s part of the problem. Each of these active protection systems takes a different approach to intercepting enemy anti-tank weapons. Each uses a different mix of radar and other sensors to detect the threat, different “hard-kill” interceptors and “soft-kill” jammers & decoys to defeat it, and different computer hardware and software to control it all. Each of them requires different training and tools to install, operate and maintain.

The Army would much prefer to standardize, as much as possible. That’s why it’s developing the Modular Active Protection System. The core component of MAPS is the electronic brain or “base kit” being developed by Lockheed Martin, which will go on every vehicle, including future designs. Then the Army will plug-and-play various sensors and countermeasures into that base kit. Some of these components will go on multiple types of vehicles, others will be custom options for a specific machine. There has to be some flexibility here, because a 70-ton Abrams and a 20-ton Stryker don’t need the exact same kinds of countermeasures and can’t physically carry the same kit anyway.

Iron Curtain test installation on a US Army Stryker

The Army also wants to be able to upgrade the system easily in the future, adding improved components as they become available, without having to redesign and re-test the whole system every time something new is added. And it wants to buy upgrades from whatever vendor offers the best value, rather than be locked into whatever vendor originally built the system. That’s the reason for the “Modular” in “Modular Active Protection System.” It’s a design philosophy also known as open architecture, which aims to accommodate any component from any company as long as they comply with common technical standards.

Lockheed’s MAPS base kit has successfully controlled a host of different systems in tests so far – sometimes in the lab, sometimes in live-fire field demonstrations. Rohall told me MAPS works with Elbit’s Iron Fist and Artis’s Iron Curtain, both “hard kill” systems that physically destroy incoming anti-tank rounds. It works with jamming/decoy “soft kill” systems like Northrop Grumman’s MEOS, BAE’s RAVEN, and Ariel Photonics’ CLOUD. And it works with a variety of sensors, including Northrop’s Passive Infrared Cueing System (PICS). This year, Rohall said, the program will focus on adding a laser-warning sensor to tell the vehicle crew when they’ve been targeted by enemy precision-guidance systems, before the foe actually fires.

Lockheed has been working on the MAPS base kit since 2014. It passed key safety reviews in 2018 – something most programs do much later in development, Rohall told me, but the Army wanted to get safety settled down earlier. In 2019 Lockheed formally delivered the first version of the MAPS software to the Army and supported live-fire testing on Bradley. It’s already built enough base kits to begin testing on Abrams, Bradley, AMPV, and Stryker, he said, but the new contract provides for it to deliver at least five more, and as many as 20, by 2023.

Army eyes TBI monitoring, wearable tech for soldiers in high-risk billets

“We are also looking at what additional personal protective equipment we can provide to our folks, especially instructors and others who are routinely exposed to blast pressure,” said Army Secretary Christine Wormuth.