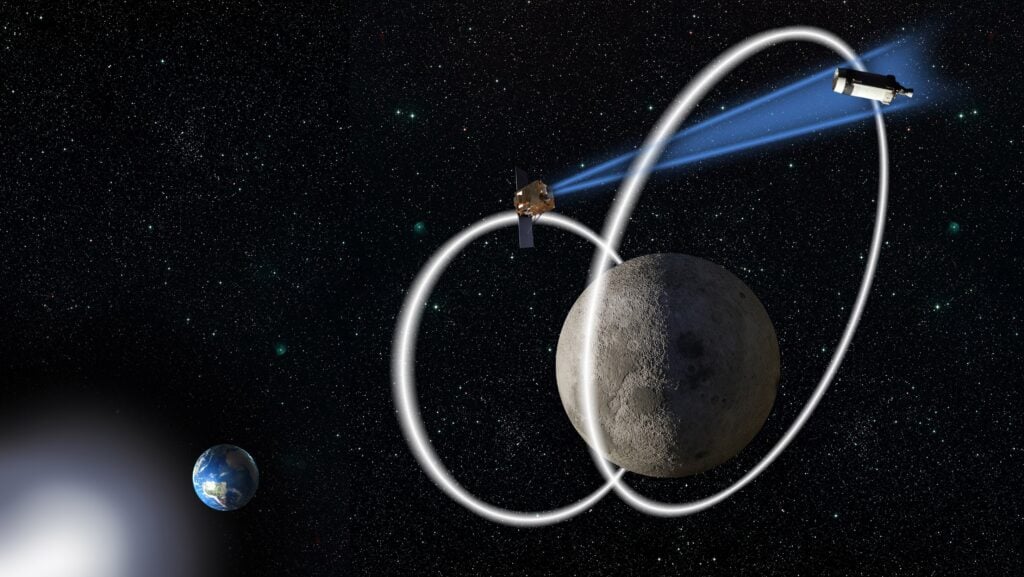

CHPS lunar patrol satellite, AFRL graphic

WASHINGTON: Advocates of expansive US ‘spacepower’ — via aggressive actions to “dominate” the heavens from Earth’s orbit to beyond the Moon — are likely to find the Biden administration much less supportive of their dreams, say a range of former DoD and US military officials, insiders and long-time space policy wonks.

Incoming space policy makers are expected to rein in the current Space Force and Space Command focus on — or, as some critic have charged, obsession with — fighting wars in space with China and Russia, out to the Moon, Mars and, in theory anyway, infinity.

For example, Space Force Vice Chief Gen. DT Thompson, in a Jan. 13 presentation to the Association of Old Crows, stressed that creating a “warfighting culture” — including training in “orbital warfare” — would be the No. 2 focus for the new service this year. Chief of Space Operations Gen. Jay Raymond, Thompson’s boss, in his November “CSO Planning Guidance” places priorities on “investments in Orbital Warfare, Space Electromagnetic Warfare, and tactical intelligence portfolios” to “protect and defend American interests in cis-lunar space and beyond.” Meanwhile DARPA and Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) have been pushing foward myriad efforts to develop new capabilities for military operations in cislunar space (between Earth’s outer orbit and that of the Moon), such as AFRL’s Cislunar Highway Patrol Satellite (CHPS) that would be DoD’s first space domain awareness (SDA) satellite in lunar orbit.

Back To Basics

Instead, multiple sources said, the Biden administration shows early signs of a return to the more historically typical Obama-era approach to space, which prioritized its role in providing critical support functions to operational commanders and troops in the field — such as satellite communications, missile warning, and position, timing and navigation capabilities. And this, several insiders say, is a move that will be welcomed by many congressional democrats, especially in the House.

When Space Command (SPACECOM) was stood up in August 2019, DoD officials and military leaders highlighted the fact that it was being established as a geographic Combatant Command with an area of responsibility starting at 100 kilometers above the Earth’s surface — rather than a functional command like the first iteration of SPACECOM (that lived from 1985 to 2002) or Strategic Command (STRATCOM), which was responsible for military space operations until 2019. This means that current SPACECOM Commander Army Gen. James Dickinson, as he explained to me in an interview on Jan. 27, technically can call in the support of other Combatant Commands, for example in targeting enemy jammers interfering with US military comsats.

However, one long-time space policy official explained that, in reality, the focus on SPACECOM’s warfighting role makes little sense. “I don’t know of a time when he [Dickinson] can stand up and say, ‘I am the supported command for x’.” Indeed, the official said, at least 95 percent of the time SPACECOM is going to be supporting operations led by other Combatant Commands.

Brian Weeden, Secure World Foundation’s head of program planning, said that another component in determining future policy is the long-standing debate “between the people who insist space will always play a support role for terrestrial ops and those who insist space will become its own separate domain of human activities, potentially even eclipsing what happens here on Earth in importance.” The latter group of “hardcore spacepower” advocates were in line with the Trump administration view, he explained, but “the majority of senior military leaders in the Space Force and Pentagon are in the support category, not the spacepower category” — and are more likely to be ascendent in the new administration.

That shift back toward the historical role for military space operations, in turn, is expected to result in more priority and budgetary focus given to protecting current capabilities and ensuring the future resilience of space assets to withstand adversary attack — a shift suggested by new Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin in his nomination hearing responses to the Senate Armed Services Committee.

“There’s nobody in charge of these fundamental missions,” said one former DoD official with an audible eye-roll. “They’re all off trying to train for how they’re going to go fight a space war, instead of worrying about the blocking and tackling of doing better at the missions they’re doing right now.”

Bathwater, Not Baby

Weeden said that the focus on ‘warfighting’ over the past year does have some merit, and shouldn’t be completely thrown out by the Biden team. “The warfighting people are correct in that the space world has tended to ignore the potential for hostile threats or attacks on space systems both in design (the lack of resiliency) and training/procedures/doctrine (the TTPs). And they are trying to do a very big culture change within the military (with a lot of young officers and enlisted) to try and inculcate that new culture while also trying to convince Congress to give them a lot of new authorities and money. Hence the “warfighting” term getting used every five minutes.”

On the other hand, he said, “they have also done a very poor job of communicating what they mean by ‘warfighting’ to the public, which has created a lot of political and diplomatic problems. So, I agree that the language needs to be reigned in and put into context, as long as that doesn’t undercut the focus on increasing resilience against threats.”

At the moment, predicting Biden space policy is “really just [reading] tea leaves … because there’s been very little said about it” by the Biden transition team, another long-time milspace practitioner cautioned. Nonetheless, the source agreed that, from all indications, a sea-change in both rhetoric and substantive priorities is most probably in the cards. “With respect to the pugilistic aspects or the ‘warfighting’ [rhetoric], I do think the Biden administration will take a traditionally softer tone on all this.”

“And, as you’re aware, the extent to which Space Force is directly linked to Trump is going to be a detriment, obviously. You know, he counted that as his number one national security accomplishment at Andrews on the way out of town.” the source added.

This does not mean, as I reported earlier, that the Biden administration is likely to try to un-make the Space Force or stand down Space Command. Nor, sources are quick to say, will the new administration ignore the very real threats to US space assets from Russia, and in particular China — with the Biden team already making it crystal clear they see China as the top US competitor on the global stage. Rather the issue is re-setting the balance between options for dealing with those threats. Thus, a refocus on resilience and ensuring that the US can continue to fight back even if an adversary strikes first in space — a position similar to how the US plans for nuclear war by ensuring “second strike” capabilities, in order to not be put in a “use ’em or lose ’em” situation, one insider explained.

It also means, other sources noted, a greater commitment to finding diplomatic solutions where possible to constrain harmful activities on orbit both in peacetime and in wartime. This is again a similar approach to how the Biden team is tackling nuclear issues, for example, planning to extend the New Start agreement with Russia that the Trump administration would have let lapse.

Personalities Count

All that said, as every wonk in DC knows, much of what happens in policy making is dependent on the personalities involved. For national security space, one of the crucial jobs at DoD is the assistant secretary of defnse for space policy, a position established at the direction of Congress only on Oct. 29. The previous top space policy position, deputy ASD, was held by Steve Kitay during the Trump administration, and then on an acting basis by Justin Johnson after Kitay’s departure in late August. Up to now, there has been little buzz on the street about who might take that post, with the Biden team still wrapped up in getting top-level secretaries and administrators nominated and confirmed.

Further, there has been little indication whether the Biden White House will decide to keep the National Space Council, which was re-animated by Trump as the focal point for policy development, or fall back on the Obama approach of leaving coordination of space policy to the National Security Council. (We’ve heard that folks with some sway are arguing in both directions.)

But besides Austin’s recent testimony, another harbinger of a return to Obama-era policy is the appointment of David Zikusoka as special assistant at the DoD office of space policy. Zikusoka, who most recently was at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CBSA), served in the space policy office under the Obama administration. Prior to joining DoD, he was then-VP Biden’s senior advisor on weapons of mass destruction and nonproliferation.

In addition, the Feb. 2 SASC hearing for deputy defense secretary-nominee Kathleen Hicks will be a further opportunity to hear Biden team views, sources say. SASC has been keenly interested in space issues, particularly those surrounding acquisition, and that is not expected to change despite the shift from Republican to Democratic control.

HASC chair backs Air Force plan on space Guard units (Exclusive)

House Armed Services Chairman Mike Rogers tells Breaking Defense that Guard advocates should not “waste their time” lobbying against the move.