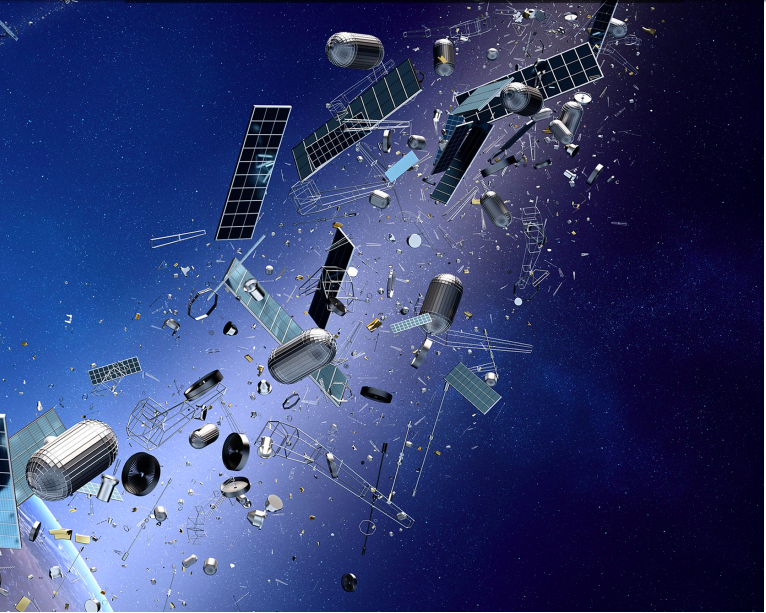

Kinetic ASATs would create enormous amounts of dangerous space debris. National Space and Intelligence Center image

WASHINGTON: The Pentagon has long professed its commitment to ‘responsible’ behavior in space, but has never clearly articulated what that means in either peace or war. This year that may change.

What’s changed? Britain sponsored a a UN resolution charging member nations to make clear their views on both what milspace actions by others they see as threatening and what they consider to be acceptable during peacetime. The Trump Administration supported it. The resolution’s goal is to reduce risks of misunderstandings and miscalculations that can lead to, or escalate, conflict, UK Ambassador to the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva Aidan Liddle told the Secure World Foundation in December.

“The United States supported a resolution adopted in the United Nations General Assembly on December 7, 2020, on reducing space threats through norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviors. The Department of Defense will be working closely with the Department of State as the United States works with other countries to realize the objectives of that resolution,” Air Force Lt. Col. Uriah Orland, a spokesperson for the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), said in an email.

The initiative is significant — and distinct from the UN initiatives launched during the Obama era and finalized in 2019 to cobble together a voluntary set of best practices for space operators negotiated at the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space in Vienna — because it specifically addresses military uses of space.

Responses from the US and other nations are required by May, a UN expert said, so they can be integrated into a report by Secretary General António Guterres by the end of August. That will be reviewed by the 193 UN members during the annual October meeting of the UN’s First Committee, which deals with international peace and security issues.

Further, the UK — likely backed by a number of other US allies including Canada — is expected to try to convince other nations to begin a more formal UN process to reach agreement around a set of ‘hard security’ norms. It remains unclear, however, how Russia and China, who long have rejected all efforts but their proposal for a legally binding treaty, will respond.

It shouldn’t be that hard to come up with a voluntary framework for milspace rules, one former US government official involved in space issues said with obvious frustration: “We just need to agree to not do stupid stuff in space.”

For example, the source said, ‘stupid stuff’ would include using destructive antisatellite (ASAT) weapons that would create mass quantities of space debris — something senior space-savvy military leaders, such as Gen. John Hyten, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, have long said the US does not want to do.

Further, the military has to make clear what it believes it needs to be able to do with military force to prevail in a future conflict in space. This means going further than boilerplate language about achieving ‘space superiority,’ or about abiding by the Geneva Conventions and the laws of armed conflict, experts say.

“What’s the role of the Space Force in all this, now that it’s stood up?” said one former DoD official with a long space-related pedigree. Space Force and Space Command, the source said, need to publicly articulate: ‘here’s how we fight and win, kill people and break things in space. That’s what they’ve got to do, and they’ve studiously avoided that so far.”

Decades of dithering

But defining military space norms for peacetime or wartime has defied legions of US policymakers and military leaders for some 40 years.

“It’s been decades of not doing that” for space, the former DoD official stressed, in contrast to the nuclear arena, where the US long ago worked out clear concepts for maintaining stability and deterrence vis-a-vis nuclear peer competitor the Soviet Union. “We don’t have the same kind of conceptual foundation for how we get to some kind of stability in this [space] environment.”

This can be traced to a whole host of reasons, according to former and current DoD officials, space policy analysts, and experts on international security, including:

- the military’s reluctance to give up any options for future action in space;

- Air Force culture and doctrine that prioritizes offensive actions in conflict;

- knee-jerk support among civilian policymakers for maintaining ‘deliberate ambiguity’ (i.e., avoiding ‘red lines’);

- the intense secrecy surrounding all things national security space; and,

- a deficit of brain-power put to answering the foundational questions involved in developing a concept of space deterrence.

“In space, we over-classify everything. And we don’t come up with that structured layered approach for how we deal with things,” Hyten told the National Security Space Association (NSSA) on Jan. 22. “Deterrence does not happen in the classified world. Deterrence does not happen in the black; deterrence happens in the white.

“We need to decide what we want to have to deter our adversaries. And then, God forbid, if conflict ever happened someday, what do we need in order to win in conflict with our adversaries,” the general said. “And those are two different things. We’ve lumped those things together as one, and think they’re the same thing. They’re not.”

DoD leaders simply have not studied how longstanding concepts of deterrence — developed by by the likes of futurist Herman Kahn and legendary game theory pioneer Thomas Schelling — can and should be applied in space, the former US government space official said.

For example, many DoD writings — such as the 2018 Joint Doctrine Note on Strategy (JDN 1-18) — focus heavily on the ability to punish an adversary using military force but fail to articulate the accompanying principle of ‘assurance’ for providing adversaries (and not just reassuring allies) proof that if they refrain from provocative behaviors they have something to gain.

“The understanding of what deterrence is has been misinterpreted, reinterpreted, run through a ringer, chopped up and turned into a hamburger. I mean, it’s just that nobody there [at DoD] seems to understand what it means exactly,” the former USG official said.

Up to now, this source explained, DoD has not formulated firm policies and courses of action for what signals need to be consistently and publicly sent to adversaries about what the US sees as verboten; how to create resiliency in space systems if deterrence fails; and what should be the set of gradually escalating capabilities to impose costs on countries who break the rules.

That lack of agreed DoD positions in turn leads to a tendency for officials to “just say no” to everything because they can’t agree, another former senior DoD official said.

Trump Administration Changes

To be fair, a number of sources note, under the Trump administration reversed years of silence — based on fears of revealing US intelligence gathering capabilities — about growing Russian and Chinese milspace capabilities. (The exception proving the rule being the loud protests regarding China’s 2007 antisatellite missile test, which of course was obvious to anyone with a high-end telescope).

Space Force chief Gen, Jay Raymond last April ripped the Russians for their most recent test of the ground-based Nudal ASAT missile; and in July cried foul over a test of the Cosmos 2543 satellite that ejected a secondary payload the US characterized as a “projectile.” He has been followed by a chorus of DoD leaders.

Such criticism is part of US “messaging” about what it considers “irresponsible” milspace behavior, Space Command (SPACECOM) head Gen. James Dickinson told the Mitchell Institute last week. “Through that particular avenue, you can kind of deduce or see what we consider [responsible vice irresponsible] norms of behavior,” he said.

He cautioned, however, to have a fulsome US approach, “it’s going to take some while … And it’ll be more of a whole of government approach.”

Dickinson makes a fair point, experts say. As emphasized in the 2020 National Space Policy, it is the State Department which has the lead for developing a US stance on space norms. That is, of course, as it should be with all diplomatic initiatives — but insiders say the National Space Council wanted to foot-stomp that message due to concerns that State wasn’t being properly supported and other agencies were moving to fill the vacuum.

While DoD doesn’t have the ultimate say in international policy development, an internal DoD agreement on space rules would be helpful in interagency discussions, experts say. For one thing, just as the Navy had to first work out how US and Russian nuclear submarines should interact (or not) under the high seas before any accords were signed, Space Force leaders have to determine how military satellites should interact (or not) on orbit before international agreements can be reached.

Indeed, Dickinson noted that one of his J5 (plans and policy) staff is “a submariner” — and that “we often have discussions where we we apply the maritime model to what we’re trying to do in space.” But, he added: “How long did it take us to establish norms of behavior or standards within the maritime domain? The answer to that is, it takes time.”

Several sources also noted that during the Trump administration, the OSD space policy shop — led by Steve Kitay until August, when he was replaced by acting undersecretary Justin Johnson — did launch an attempt to gather DoD stakeholders to develop a baseline framework for delineating responsible from irresponsible behavior. Participants included SPACECOM, Space Force and even the NRO; but no public document has been released.

Further, it is not clear how or whether the Biden administration will continue the effort — given the fact that it will take time for the White House to put in place the DoD principles responsible. Biden has named David Zikusoka as special assistant at the DoD office of space policy to handle the transition, but not someone to fill the top-level job of DoD assistant secretary for space policy.

That said, there is every reason to expect that Biden’s DoD will be supportive of norm setting. Indeed, deputy defense secretary-nominee Kathleen Hicks told the Senate Armed Services Committee in her written answers to questions prior to her hearing today that norms are part of any strategy to help reduce threats to US space systems. “It is essential to continue developing best practices, standards, and norms of behavior in space in order to deter threatening behavior and uphold the rights of all nations to use space responsibly and peacefully,” she wrote.

On the other hand, insiders and experts said, the lack of any substantive US proposals on milspace rules over many years can be laid squarely at the feet of the defense establishment. This is because national security officials, whether civilian or military, have been loathe to close off any future options for military response to adversary actions in space.

This is despite the fact that the US has signed a number of agreements, even legally binding treaties, that limit military options in other domains — such as the Biological Weapons Convention, or the US-Soviet Incidents at Sea agreement. In fact, as many experts point out, a decision to keep all options open is not a get-out-of-jail-free card. It also imposes lost opportunity costs regarding options to solve issues before they become problems requiring military response.

Further, as Secure World Foundation’s Brian Weeden and Victoria Samson noted in an op ed back in May, the primary motivation for the new DoD openness about foreign threats to space systems doesn’t really seem to be aimed at norm setting. Instead, the impetus for the strong rhetoric about Russian and Chinese programs seems to be “because talking publicly about space threats helps reinforce the narrative that the United States needs both U.S. Space Command and the U.S. Space Force to combat counterspace threats.”

In other words, it’s good PR for the two new organizations to shore up support from the US public, and more importantly, Congress (which has the power of the purse.)

After shooting down Iranian munitions, Jordan defiant in uncomfortable spotlight

Amid Iranian criticism, “Jordanian leaders have been very clear to portray their action as defensive and in protection of their own sovereignty rather than any act in support of Israel, and this is sincere,” an analyst told Breaking Defense.