Launch of Army-Navy Common-Hypersonic Glide Body (C-HGB) in Hawaii on March 19, 2020.

WASHINGTON: The Pentagon’s director for hypersonics R&D and a range of defense experts are pushing back against a skeptical study of hypersonic weapons by arms control advocates at the Union of Concerned Scientists. The UCS gets something wrong at every step of their analysis, they say.

The study, released days before President Biden’s inauguration and touted in The New York Times, argues that the investment for hypersonics is out of all proportion to the strategic benefits.

Cameron Tracy, Union of Concerned Scientists

The Union of Concerned Scientists argues that hypersonics aren’t the unstoppably fast superweapons that they are often described as, not only in news stories but even in serious academic articles. So, at about $3.2 billion in R&D for 2021 alone, “the current number is pretty excessive, based on what we know about the performance, what these can do relative to what the weapons we already have,” Cameron Tracy, the lead author of the UCS study, told me. “We’re not really arguing against research on hypersonic flight, [but for] a significant reduction in funding for development of these weapons.”

But that conclusion is built upon a fatally flawed analytical foundation, argue our sources in the Pentagon and defense thinktanks.

“The [UCS] analysis compares intercontinental ballistic missiles to hypersonic glide bodies, and the authors then make the conclusion that hypersonic glide bodies don’t offer much benefit for that mission, because they don’t significantly reduce time to target and they can theoretically be detected,” Michael White, the principal director for hypersonics in the Pentagon undersecretariat for research & engineering, told me. “But for that mission, the fact that you get there five or 10 minutes faster is not the value proposition, and just because you can detect an incoming hypersonic missile that does not mean you can shoot it down or determine where it is going to impact.

“The key attribute for a hypersonic weapon is the trajectory uncertainty due to maneuverability enabled by high speed flight within the atmosphere,” he said.

In other words, the primary reason Russia and China want hypersonic weapons is that they’re extremely hard to intercept, even more so than ballistic missiles. Moscow has been paranoid about US missile defenses neutralizing their nuclear arsenal at least since Ronald Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative back in 1983, even though “Star Wars” never materialized. Beijing has a relatively small ICBM arsenal, so they keep a careful eye on any improvements to America’s current, very limited ballistic missile defense.

“Their math is relatively simplistic and their assumptions are wrong,” one senior defense official told us, “and they’ve done analysis in a [mission] that’s irrelevant to the DoD investment strategy.”

“Their criticisms of some claims surrounding hypersonic weapons are accurate, but the subset of claims they chose to address were among the least compelling ones,” Bryan Clark, a retired Navy strategist and submariner now with the Hudson Institute, said.

“In several respects, the authors set up a straw man and then demolish it,” Tom Mahnken, a former defense official and Navy veteran who now heads the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments, argued. “The authors are looking at one particular case: intercontinental boost-glide vehicles…but I don’t know many folks who envision the US, Russia, or China investing in large numbers of intercontinental hypersonic boost-glide vehicles.”

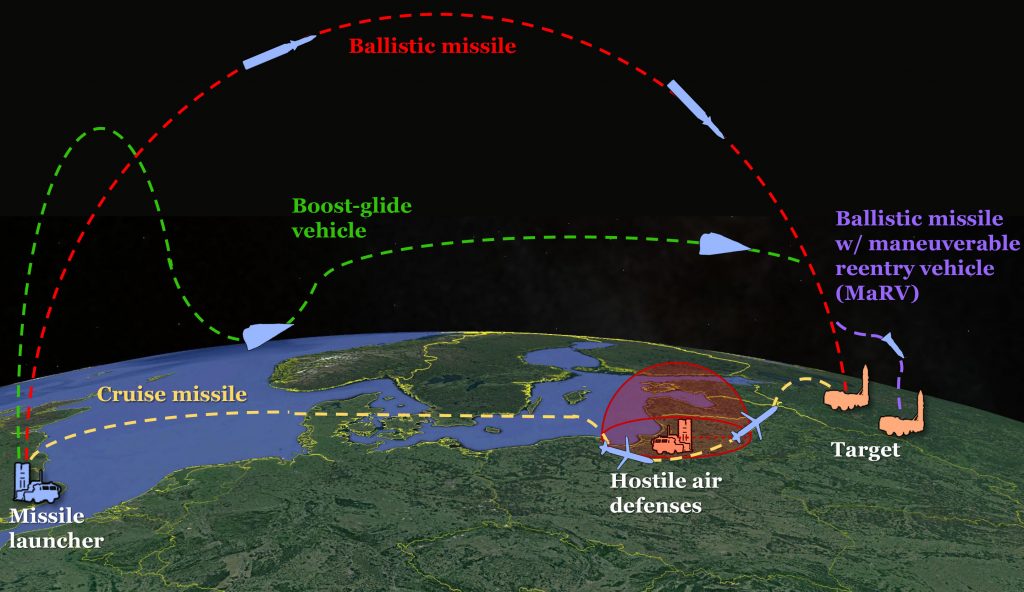

Notional flight paths of hypersonic boost-glide missiles, ballistic missiles, and cruise missiles. (CSBA graphic)

“I don’t think you can use this analysis to draw broader conclusions about the types of shorter-range, conventionally-armed hypersonic weapons that states are also investing in,” agreed CSBA scholar Evan Montgomery.

And those shorter-range hypersonic missiles are what the US is actually building, not intercontinental weapons.

Michael White

“What we are doing is developing a family of air, land, and sea-launched, theater-range, conventionally armed systems to defeat targets of critical importance so that we can maintain tactical battlefield dominance in a high-end fight,” said White.

“In the theater mission, when we look at comparing a long-range strike with a traditional subsonic cruise missile, to that same mission using a hypersonic glide vehicle or cruise missile, the speed difference is a factor of at least 10,” White said. “So instead of taking two hours to fly the route, we can get there in 12 minutes.”

With that kind of speed, and a range that – while shorter than ICBMs, is longer than many existing US missiles – theater hypersonics can perform time-critical strike missions that US forces simply can’t do today.

Now, Russia and China are developing intercontinental hypersonics – so does the UCS analysis apply to those weapons?

To an extent, said CSBA’s Montgomery. “If those weapons are not as fast as, and more detectable than, sometimes portrayed, that should probably limit concerns about the risk they pose,” he told me. “If the technical analysis is correct, then it would suggest hypersonic weapons are unlikely to seriously erode strategic stability.”

A Russian MiG-31 with a Kinzahl hypersonic missile.

The US has no such anxieties about its ICBMs being countered. But it sees theater hypersonics as a way to penetrate theater air and missile defenses that could keep its current missiles, fighters, and bombers at bay in a conventional conflict.

“The warfighting effect of these capabilities is transformational,” White said. “We’ve done the analysis, and fighting the tactical fight with and without them, there’s a huge difference.”

Lockheed wins competition to build next-gen interceptor

The Missile Defense Agency recently accelerated plans to pick a winning vendor, a decision previously planned for next year.