A soldier tests the ENVG-B inight vision goggles n 2019. (Chris Bridson / Army)

WASHINGTON: The Army aims to outmaneuver and outthink its adversaries so thoroughly it achieves “decision dominance,” its generals said in unison this week. Will the new term became the latest bureaucratic buzzword or shed real light on how the future force should fight?

Gen. James McConville

I first noticed “decision dominance” pop up during a morning panel on the first day of AUSA’s virtual Global Force Next conference, but the term really thundered forth that day during midday remarks by the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. James McConville.

The Army must move faster, McConville, declared, both as an institution developing new weapons – not in decades, but in a few years – and as a battlefield force destroying enemies – firing artillery, not minutes after spotting a target, but seconds.

“Today, we’re getting from [a list of desired] characteristics to fielded capabilities in as short a time as three years,” McConville said. “This allows us to think and innovate faster. And as a result we operate faster: For example, at last year’s Project Convergence exercise, we engaged targets in tens of seconds instead of tens of minutes.”

“Speed, range, and convergence give us the decision dominance, and decision dominance gives us the overmatch we need,” he said.

But the chief of staff didn’t explain further. Instead, he left it to the service’s modernization czar, Army Futures Command chief Gen. John “Mike” Murray, the following day.

Gen. John Murray, first chief of Army Futures Command, speaks at its formal activation in Austin.

“Yesterday, you heard the chief mention five key [terms],” Murray said: “speed, range, convergence decision dominance, and overmatch.” Each has multiple meanings:

- Speed refers to the physical speed of weapons like futuristic helicopters and hypersonics streaking across the battlefield, the general said, but also to the cognitive speed of an AI offering a commander options and that commander making a faster and better-informed decision as result – leaving the enemy commander a fatal step behind.

- Range refers to physically outreaching the enemy with longer-range weapons, he said, but also to prepositioning the right forces, gear, and supplies on friendly territory — building relationships with allies, deterring adversaries, and responding immediately to local crises. “The quickest way to get from Point A to Point B is to already be at point B,” he said.

- Convergence refers to connecting different Army and even non-Army systems on a common data-sharing network, as at the Project Convergence wargames last fall, Murray said. But it also refers to bringing together different institutions, whether across the Army or between the Army and private industry.

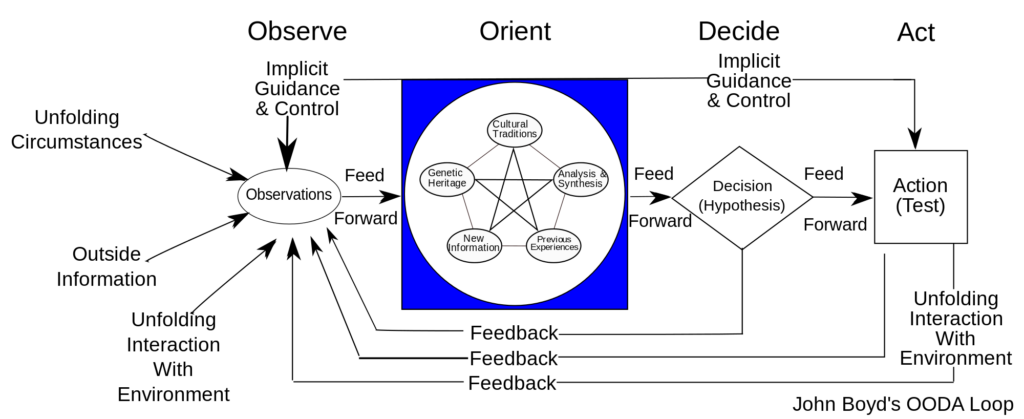

- And then we come to decision dominance. “This is a developing definition,” Murray cautioned. “But right now, [decision dominance] is the ability for a commander to sense, understand, decide, act, and assess faster and more effectively than any adversary.”

That’s a variant of Air Force Col. John Boyd’s famous OODA loop, developed first to describe jet fighter duels but later expanded to all kinds of time-sensitive decision making: Observe the situation, Orient yourself to it, Decide, and Act. The theory is that mental quickness can be decisive, with the side that cycles through the OODA loop faster getting a compounding advantage over time, with the quicker party changing the situation faster than the slower can keep up with, causing them to be increasingly disconnected from reality.

Col. John Boyd’s “OODA loop” concept

Murray didn’t lay out this background theory, but he did say that decision dominance “will create a significant, not only tactical but operational and strategic, advantage, on any future battlefield” — in Army terms, overmatch.

“I hesitate to say that it may be a future offset,” he said, using the US term of art for a game-changer that lets outnumbered US forces defeat hordes of well-armed adversaries. “But I do think it will [be] a significant advantage to any, any commander of a future battle.”

“That’s ultimately what Project Convergence is all about,” Murray added. “That’s the learning opportunity that we were seeking, is how do we achieve that convergence and that decision dominance on a future battlefield.”

“It is much more than technology,” he said. “It’s about what we will fight with but it’s also just as much about how we will fight, and how we are organized for that fight. It’s about scaling [from small experiments to real operations], not only for the Army, but for the joint force and driving solutions back to the joint staff” as it works on the Joint Warfighting Concept and Joint All Domain Command & Control.

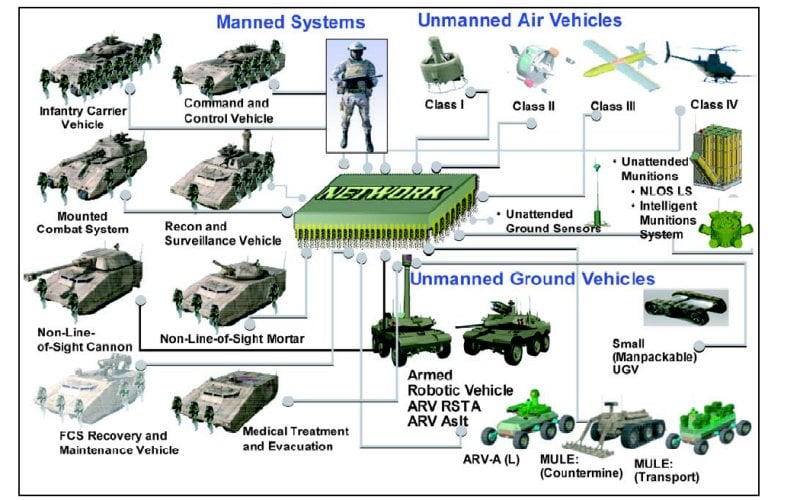

But wait a minute, I asked in the online Q&A. Doesn’t this sound a lot like the hubristic claims of the Future Combat System, cancelled in 2009, which promised its new technology would allow future commanders to “see first, understand first, act first, and finish decisively?”

Army slide showing the elements of the (later canceled) Future Combat System

“What I would tell Sydney is that one of the first things that I did… back 2018 … was pulled the lessons learned documents from FCS and Crusader and Comanche and several other programs that were less than successful,” Murray replied. “There was extensive writing on what caused FCS to fail.”

One major factor? “Establishing too early [performance] requirements without fully understanding the technologies, without fully understanding that the timeline those tech those that those technologies will mature along, without fully understanding the integration that would have to happen,” Murray said.

But that’s where “convergence” comes in again, because the Army is doing it now, before trying to nail down the final system. “Project Convergence, Sydney, as you know, is S&T [science and technology] efforts that we’re pulling out of our labs,” he said: It’s taking placing before the start of formal programs of record with their locked-in requirements that are too late to change.

In other words, while the Army knows it wants to achieve “decision dominance,” it’s leaving itself plenty of room to experiment and figure out how to achieve it.