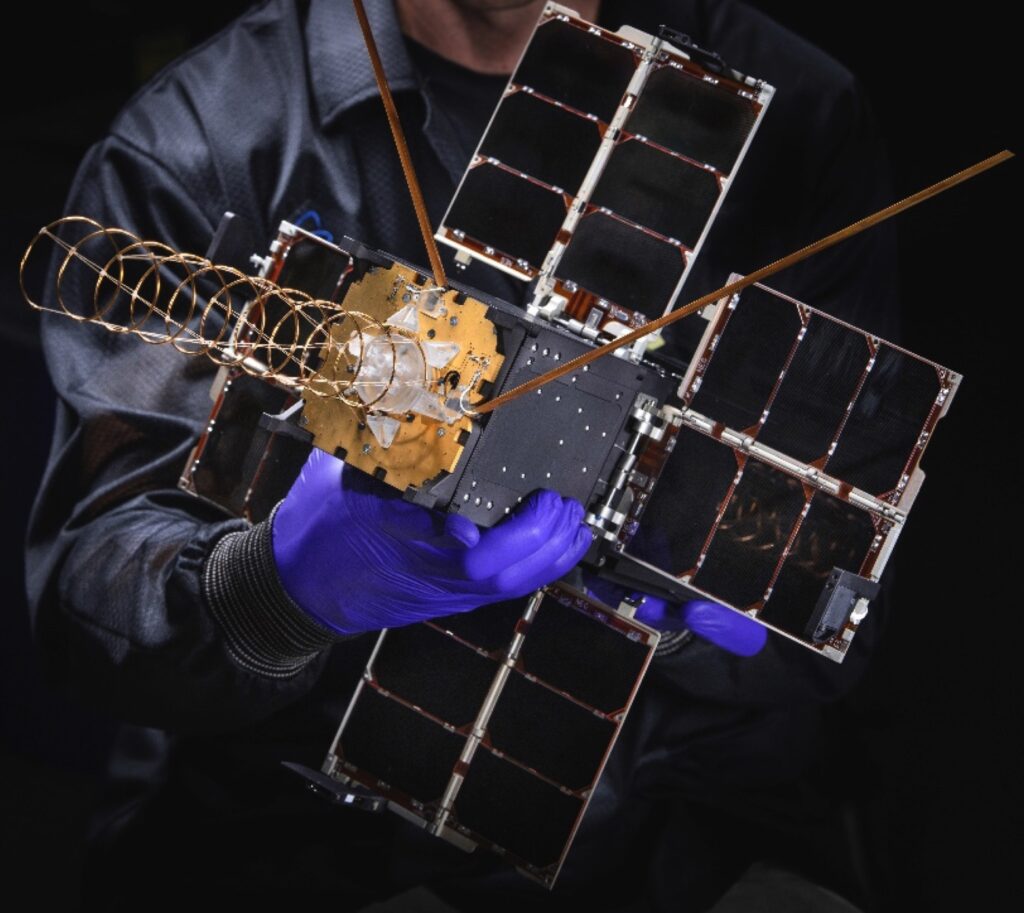

Gunsmoke-J experimental satellite, Army image

WASHINGTON: The Army is negotiating with the Intelligence Community and Space Force about ensuring operational control of any future Army-built ISR payloads hosted on DoD, IC and/or commercial satellites, says Willie Nelson, the de facto head of Army space programs.

“This is a watershed,” said Doug Loverro, former head of DoD space policy and a long-time player in space intelligence operations. “It represents the increased importance of tactical overhead support to Army forces for long range fires.”

Why? If the service wins even a modicum of control over where future IC ISR birds are ‘pointed’ — a prerogative the IC traditionally has zealously guarded — it would represent a major break with the past.

For decades, a small committee has made the decisions about where America’s spy satellites are tasked and who gets priority access to their data steams. Today, that committee is led by the director of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), which sets the operational requirements for the NRO to meet when it builds spy sats — as well as for any commercial ISR sat data contracted for by NRO. NGA, in effect, also has its finger on the trigger as to who gets priority for the data streaming from those satellites.

The Army doesn’t want to totally take over the steering wheel of NRO-operated imagery or signals intelligence satellites, or (at least for the moment) build its own constellation of ISR sats. Instead, Nelson explains, it is focused on ensuring that ISR (or any other) payloads it might build in future for hosting on non-Army satellites will be available when the service needs them.

One of the Army’s end-goals with its multi-pronged Tactical Satellite Layer (TSL) experiment is to ensure “dedicated” access to space-based intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance data needed to guide missiles to targets deep inside Chinese and/or Russian territory, Nelson told Sydney in an interview. Those long-range precision fire capabilities are one of the Army’s top priorities, as they are considered by service leaders to be the linch-pin for future all-domain operations.

Army requirements, he stressed, are to “sense deep, engage deep, target deep.”

The Army wants a “cooperative relationship” where ISR constellations of small satellites are managed day-to-day and launched by the traditional milspace operators, Nelson said.

This includes the NRO, and the Space Development Agency (SDA) that is working on a constellation of small satellites for communications and another for missile tracking. SDA, in turn, is expected to soon come under Space Force head Gen. Jay Raymond as part of a reorganization of Space and Missile Systems Center into a new Space Systems Command.

“We are doing this working with the Space Force and SDA and the Intelligence Community,” Nelson explained.

On the other hand, he stressed, the Army wants to be “tied at the hip” in the process for establishing how data is distributed and to be “able to directly reach out and touch and task those capabilities deliberately” rather than in an “ad hoc manner” or under a priority list made by someone outside the Army. The requirement, he said, is for “dedicated capacity, so that it is there when it’s needed.”

Battlefield Needs Vs. Strategic Needs

The Army’s campaign to ensure 24/7 access to space-based ISR data dates back all the way to Desert Storm in 1991, explain experts inside and outside of DoD. For nigh on 30 years, military users have complained bitterly that NRO and NGA don’t always meet commanders’ needs for near-real time battlefield ISR for targeting enemy assets.

“There has been a longstanding concern among DoD users of space-based ISR: will the IC be there for me when I need them? Trust has to be built,” said one former DoD official.

One longstanding attempt to ameliorate this disconnect has been the military services’ Tactical Exploitation of National Capabilities Program (TENCAP). Keith Masback, once the Army’s director of ISR Integration, explained that “the TENCAP approach is a cooperative effort between the IC and DoD to build deployable systems that facilitate more rapid dissemination of data from national space assets to tactical forces.” But, he added: “While those investments do accelerate delivery, they don’t get at the larger issue of the prioritization of tasking the assets.”

One longstanding attempt to ameliorate this disconnect has been the military services’ Tactical Exploitation of National Capabilities Program (TENCAP). Keith Masback, once the Army’s director of ISR Integration, explained that “the TENCAP approach is a cooperative effort between the IC and DoD to build deployable systems that facilitate more rapid dissemination of data from national space assets to tactical forces.” But, he added: “While those investments do accelerate delivery, they don’t get at the larger issue of the prioritization of tasking the assets.”

Battlefield needs, commanders have consistently argued, always are susceptible to being out-competed by the strategic intelligence (e.g. nuclear-related) priorities of the IC, the president and even the State Department.

The IC argues that those assets — imagery satellites, radar satellites, signals intelligence satellites — are needed by numerous customers, who in turn have different concerns. Space-based ISR has been a limited resource because ISR satellites have been enormously expensive to build, and relatively few and far between. The job of the NGA-led committee, therefore, has been essentially to perform triage among an ever-more needy user base.

Masback, who was once chairman of the tasking committee, understands both sides of this challenge. “Warfighting commanders are unwavering and unambiguous regarding their need for assured access to ISR. The military services maintain organic ISR to meet their respective doctrinal needs, but the deep strike mission has always been vexing as it creates a reliance on national-level space assets. ‘Forces in contact’ always get the highest priority, but there is a need to timely respond to high-interest strategic requirements as well. It’s a carefully orchestrated 24/7/365 balancing act that isn’t necessarily prepared to support targeting, battle damage assessment, and re-strike at the speed of hypersonics.”

At the same time, the need for up-to-the-minute, on-demand ISR has become even more important to the Army because of its plans for hypersonic missiles and other long-range weapons. They simply will not be usable without near real-time information about targets for them to hit. While drones have been providing the Army and other services on-demand ISR for years, they are increasingly at risk from adversary anti-aircraft capabilities.

“The services have grown used to having that kind of overhead reconnaissance at their beck and call, but they know that all the fights in the future will not be in such a permissive air environment to allow small mobile UAVs to support their needs. And, as the range of fires increase, and the pace of combat quickens, you need to extend that range through space. So small tactical satellites ‘controlled by local commanders’ are the answer,” Loverro said.

Rob Zitz, a former senior government official who held leadership roles in Army Intelligence, NRO and NGA, was much more blunt. “The Army simply cannot wait for approvals from the IC to prioritize their needs when minutes matter,” he told me in an email. “The Army needs information when and where they want it. The IC should not get a vote on what Army needs or how Army executes combat missions.”

More Suppliers, More Options

In recent years, technologies to push down the size, weight and power demands for components, along with rapidly declining costs of launch, have spurred a boom in commercial satellite operators specializing in high-fidelity imagery, radar and even RF-tracking satellites.

Indeed, the IC and DoD have been trying to figure out how best to tap into those commercial capabilities. This includes directly buying data and/or services; efforts now being pursued by the IC via an NGA council. It also includes working with commercial firms to adopt and adapt their kit and capabilities; part of the SDA’s strategy for building its National Defense Space Architecture. The Space Force, meanwhile, now says it too is considering buying commercial ISR services to improve warfighter access.

The ongoing proliferation of satellite technologies opens the door for the natsec community to consider new ways to improve exploitation of space-based ISR, former Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence Kari Bingen told me in an email.

“DoD and the IC now have a great opportunity to experiment — as the National Defense Strategy says — with different models for tasking, different pathways for distributing satellite data,” said Bingen, who recently joined commercial RF geolocation sat firm Hawkeye 360. “If the Army, NRO and NGA are all coming to the table to discuss in good faith — that’s a great development. It’s a first step, but a good thing.”

It also, several insiders said, gives Army brass a lot more ammunition to push the IC on the issue than they have had in the past.

“The legacy tasking model of ‘one control’ over everything is being stressed. And given DoD’s challenges in meeting its changing ISR needs, it’s arguably not the right approach going forward — it’s inefficient,” one former DoD official explained.

From Kestrel Eye to Hosted Payloads

Kestrel Eye, Army image

The Army has experimented with developing its own micro-satellites to provide ISR, most notably with the Kestrel Eye project initiated in 2007. Kestrel Eye, a mini-fridge sized electro-optical satellite with a two-meter resolution, was launched in 2017 and operated for 10 months.

According to an undated Army Space and Missile Defense Command fact sheet, a Military Utility Assessment (MUA) “was conducted at U.S. Pacific Command” and resulted in two major findings: that Kestral Eye “successfully provided rapid imagery directly from the satellite to the tactical ground station;” and “the overall assessment conclusion recommending further development of the system to fully demonstrate its readiness to be a program of record.”

That did not happen. Instead, the Army approved a strategy “to demonstrate” obtaining tactical ISR (as well as communications capabilities) from Low Earth Orbit satellite constellations by “leveraging” DARPA’s Blackjack program and commercial capabilities.

Fast forward to today, where the Army is working with SDA to both host payloads and develop a ground station, TITAN, to link to SDA’s Transport Layer of communications/data relay sats. (Meanwhile, the SDA and NRO are discussing how spy sats might directly link with SDA’s planned Transport Layer of data relay sats as one option speeding imagery to warfighters for use in targeting.)

Indeed, the service’s current Tactical Space Layer experimentation program was established sometime in 2019, according to an Army press release, under an Interagency Memorandum of Agreement among the Army, NRO, NGA and DIA.

How and why that change happened isn’t documented anywhere that we could find. But there have been plenty of rumors floating around that when the Army finally got serious about building its own satellites, NRO and NGA weighed in to argue that this would be inefficient. Thus, they put the kibosh on the service’s plans. In other words, the current Army approach could be seen as a politically savvy fall-back position designed to tack around bureaucratic obstacles.

In any event, Nelson and other Army officials insist nowadays that the service has no plans to buy, own and operate satellites.

Rather, the TSL concept, being spearhead by the Assured Positioning, Navigation and Timing/Space (APNT/Space) Cross-Functional Team (CFT) that Nelson leads, is aimed at prototyping sensor payloads — and it is not even yet a program of record at all.

Those experimental payloads are largely focused on ISR capabilities, but also on alternatives to GPS for positioning, navigation and timing (PNT).

“Expanding U.S Army access to space-based capabilities will allow deep sensing in contested operational environments to enable responsive and accurate long-range precision fires, provide resilient communications, and assured PNT,” an Army spokesperson said in an email.

TSL Experiments

The Army on April 19 announced it had approved an Abbreviated Capability Development Document (A-CDD) that details service requirements, and allows rapid prototyping and experimentation through DoD’s Middle Tier Acquisition process.

“The A-CDD supports the development of Tactical Space Layer prototyping capabilities and solutions that will enable deep-sensing, targeting, artificial intelligence / machine learning, positioning, navigation and timing, and tactical communications to shorten sensor to shooter timelines,” the Army spokesperson explained.

“Funding provided will support FY21-23 development of prototypes and experimentation in coordination with the Intelligence Community, the Space Development Agency and US Space Force,” the spokesperson continued. However, how much funding is still in flux as the Army massages 2021 and future year budgets.

The TSL includes at least three ongoing Army efforts to build experimental satellites/payloads: Gunsmoke, Lonestar and Polaris.

The first Gunsmoke, a tiny Cubesat called Gunsmoke-L, was launched Feb. 20; the second, Gunsmoke-J, on March 31. A third should be launched soon, an Army press release says. Gunsmoke has been developed with support from DoD’s Office of the Undersecretary of Research & Engineering, under a contract with Dynetics, a subsidiary of Leidos.

Lonestar is designed to warn commanders about GPS jamming on the battlefield and to characterize the signals environment in a contested area so that the Army can overcome the problem and operate effectively. Dynetics also is the prime, and it delivered two “tactical space support vehicles” under the project in July 2020; launch is expected something this year.

Polaris also is aimed at APNT, but its primary goal is to provide an alternative to traditional space-based GPS in contested battle spaces. According to Tom Webber, head of SMDC’s Technical Center who is charged with the effort, the Army sees Polaris as a possible payload on SDA’s Transport Layer.

Looming Space Force Food Fight

The Army’s hopes for ‘organic’ space-based capabilities may face another hurdle going forward besides breaking away from the IC — competition with the Space Force. The newest branch of the military did not exist when the Army was transitioning from Kestrel Eye to TSL.

A number of sources inside and outside DoD say that Space Force leaders have been casting covetous eyes on all space acquisition programs, from satellite communications to ISR to missile warning and tracking — perhaps even hoping to subsume NRO and the Missile Defense Agency. As noted, it also is seeking to expand its mandate to provide commercial satellite communications to DoD users to include remote sensing, PNT and ISR, Space Force Deputy Lt. Gen. DT Thompson recently said.

Maj. Gen. DeAnna Burt

Dave Deptula, dean of the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, yesterday questioned Space Force’s Maj. Gen. DeAnna Burt about whether the Army is overstepping Space Force bounds with its TSL effort.

“When we go to a fight, it’s a joint fight, and so it’s a Joint Task Force Commander that’s doing the work,” he said during a virtual interview with Burt. “I mean the Air Force doesn’t have its own organic constellation of satellites to do strike targeting and planning … and the question is, why does the United States Army, as a separate service, need to have its own organic constellation?”

Burt — who wears two hats: as head of Space Command’s Combined Force Space Component Command (CFSCC); and deputy commander of Space Force’s Space Operations Command — downplayed any potential rivalry, however. She explained that the 1947 Key West agreement creating the Air Force didn’t result in the other service’s giving up planes — instead there are a variety of aircraft dedicated to their specific needs.

“So, I would say the same in the Space Force. We’re trying to find that balance of what space capabilities need to be retained with maneuver forces, and to protect the force, versus what are the things that are purely in the domain, or have a global effect or impact global combatant commanders, that need to be in the Space Force. So, that’s been the dialogue that’s ongoing.”

This includes, she said, LEO-based satellite constellations that the Army is interested in.

That said, she stressed that the use of any such service-specific space capabilities would “need to be coordinated and be deconflicted with US Space Command.” The goal, she said, “is to figure out how to bring it together, to synchronize across the enterprise. … and then, how do we command and control and orchestrate those so that they are not either fratting [i.e. engaging in fratricide] each other, or we’re double tapping targets if we don’t need to.”

Burt also said that with regards to IC assets, Space Command is working every day via the National Space Defense Center (NSDC) to coordinate on command and control — including when Space Command might need to take over to protect those assets. She explained that NSDC “has the lion’s share” of the responsibility for coordinating with the NRO, NGA and other IC agencies on how to best bring “intelligence capabilities to the protect and defend mission.”

Masback also believes that the Army and other service needs will ultimately best be served by a networked, hybrid approach. “The services will need to integrate their organic ISR assets while leveraging those of their joint and combined partners, as well as creating agile streamlined access to traditional national space assets, the new SDA architecture, hosted payloads, and commercial capabilities to ensure that they can support their respective operational warfighting requirements. This will be their optimal pathway to timely, assured access to ISR.”