President Joe Biden (left) talks with Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin (center) and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Army Gen. Mark Milley (right). (DoD photo)

WASHINGTON: Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin has signed an unclassified, formal memo mandating that the Pentagon abide by a framework set of norms for military activities in outer space — a first for the Defense Department, despite long-standing verbal pledges by top brass about “responsible” behavior in space.

The July 7 memo, obtained by Breaking Defense, is “the first time, to my knowledge, that the DoD has released an unclassified statement about norms,” said Doug Loverro, former head of DoD space policy.

At the same time, the memo leaves DoD an enormous amount of operational flexibility — including the possibility of testing and using weapons (for example, lasers or even ground-based missiles) to take down adversary satellites as long as any space debris created is not “long lived.” As one insider said, US military leaders always will avoid, if possible, making binding “red line” commitments.

The one-page memo lays out five “Tenets of Responsible Behavior” for DoD space operations:

- Operate in, from, to, and through space with due regard to others and in a professional manner.

- Limit the generation of long-lived debris

- Avoid the creation of harmful interference.

- Maintain safe separation and safe trajectory.

- Communicate and make notifications to enhance the safety and stability of the domain.

It further tasks Space Command head Gen. Jim Dickinson to “collaborate with DoD stakeholders to develop and coordinate guidance regarding these tenets and associated specific behaviors for DoD operations in the space area of responsibility” and make recommendations to Austin for approval. Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Colin Kahl is tasked to “lead DoD activities to advance these tenets, as appropriate, within the U.S. Government and in international relations.”

The Good: Largely Positive Response

A number of outside experts welcomed the memo — which reportedly has been in the works for more than a year, dating back to the Trump administration.

“I think it’s actually a pretty good start to identifying and formalizing what DoD sees as norms of behavior,” Victoria Samson, head of Secure World Foundation’s Washington office, said.

“I would say that this is a good start,” said Jessica West, of Canada’s Project Ploughshares. She further praised DoD’s commitment to improving notifications and communication as “a valuable and very much welcome step beyond principles to practice. We need more of this.”

“I think the key piece here is increased communications to lower the chance of unintended escalation or entanglement,” agreed Kaitlyn Johnson, deputy director of the Aerospace Project at the Center for International and Security Studies (CSIS). “This means that DoD (and the IC) needs to prioritize de-classification of assets and missions, as well as establish declaratory policies to better communicate understanding of what is ‘responsible behavior’ or, as the first tenet describes, a ‘professional manner’.”

Brian Weeden, who heads up SWF’s program planning, echoed: “It’s definitely very basic, but given how much effort went into this I think it’s a great starting point.”

Weeden added: “The key, as always, will be how it is interpreted and applied. There are some vague terms in here that could be interpreted very broadly, but that is to be expected. I hope to see similar official policies from other major space powers and also some discussions between them about how to interpret some of these terms in a common way.”

Plus Cà Change, Plus C’est La Même Chose?

“The document reiterates key principles in the Outer Space Treaty, such as due regard and the avoidance of harmful interference as well as the long-standing expectation that states limit the creation of long-lived debris,” West elaborated. “These are important commitments. But they aren’t new. And concepts such as due regard remain vague. So how will this change practice? What will the US military do differently to improve the deteriorating security situation in outer space?”

“The sense I get is that DoD is committing to many of the principals that the space policy community has been advocating for to increase sustainability and stability in the space domain — which is definitely in the United States’ national security interest,” said Johnson.

Samson noted that the DoD commitments to limit the generation of long-lived debris and improved communications “actually showed up quite often in the national submissions made in response” to the UN General Assembly’s resolution in December 2020 (UNGA 75/36).

That resolution, which was sponsored by the United Kingdom, encourages member states to provide views on existing and potential threats to space systems, and to “characterize actions and activities that could be considered responsible, irresponsible or threatening and their potential impact on international security.”

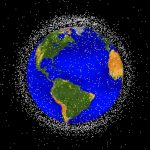

A NASA image showing space debris in orbit.

The resolution served in part as a forcing function for DoD to articulate an internal position on norms. And, indeed, the US response to the resolution, provided to the UN in May, calls on all nations to “limit the purposeful generation of long-lived debris.” (Notably, France, which has said it intends to pursue on-board lasers to shoot back at threatening enemy satellites, also made the same call in its submission.)

Similarly, Johnson noted that the DoD tenets echo the 2019 UN guidelines on the “Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space.”

The Bad, And Potentially Ugly

The biggest concern with the new DoD principles is the potential that rather than protect the already congested and risky space environment, codifying a norm against long-lived debris may instead actually provide cover for countries to do anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons tests.

“The commitment to avoiding ‘long-lived’ debris is, ironically, concerning,” West said, noting that top DoD leaders — including Gen. John Hyten, vice chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — have for some time been making similar verbal pledges.

First of all, West and others explained, there isn’t any definition in the US, much less internationally, about what that term “long-lived” actually means.

Second, there is precedent for countries justifying a destructive ASAT test in part by claiming it will not create long-lived debris. When India conducted its March 2019 KE-ASAT test, New Delhi asserted that the configuration of the low-altitude test would result in little debris spewing into heavily used orbits where it would linger for many years — an assertion that proved false.

The US, too, made a similar claim regarding debris when the George W. Bush administration shot down a de-orbiting satellite in 2008 in Operation Burnt Frost using a ship-launched anti-ballistic missile — a move the White House argued was necessary for safety reasons, but many independent experts decried as a de-facto ASAT test.

“The dynamics of the debris field from Burnt Frost were very similar to the debris field from the Indian ASAT test. Until I see a public analysis showing otherwise, my conclusion is that those types of intercepts will always end up with at least some debris getting thrown into higher orbits,” Weeden noted.

The memo’s phrasing very clearly would allow another Burnt Frost, said Loverro.

“We know that existing commitments to minimize “long-lived” debris are no longer sufficient to maintain the safety, sustainability, and security of the space environment,” West elaborated. “And we have seen many times over how emphasis on the undefined concept of ‘long-lived’ has been used as a loophole for weapons tests and other activities that do create debris, from Burnt Frost to Mission Shakti by the Indian government.”

Space Force EW unit working to integrate new weapon systems, intel personnel

The Space Force’s Delta 3 is responsible for organizing, training and equipping Guardians for electronic warfare missions involving satellite communications, as well as sustaining related offensive and defensive EW systems.