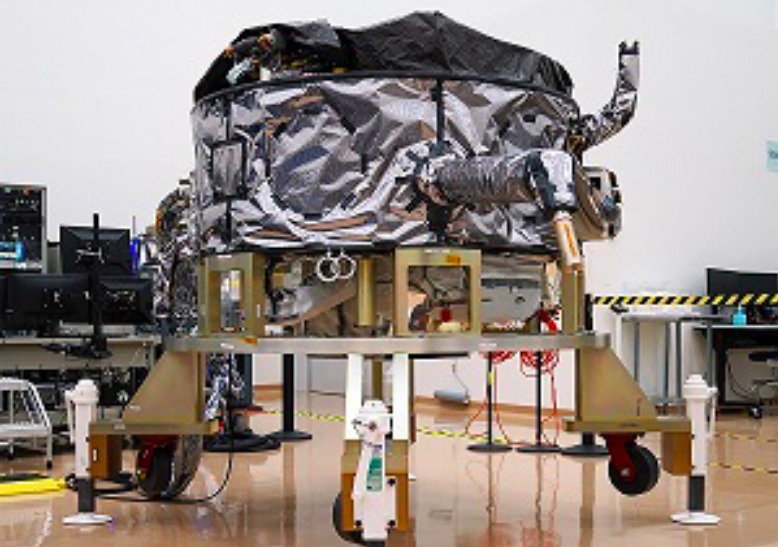

Northrop Grumman’s ESPAStar-D bus will be integrated into AFRL’s NTS-3. (Northrop Grumman)

UPDATED: To clarify costs. WASHINGTON: Ground integration tests of the experimental NTS-3 satellite, designed to demonstrate alternate positioning, navigation and timing capabilities to those now provided by GPS, will begin next month, an Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) official tells Breaking Defense.

“We’re just getting into what we call the ‘end-to-end system integration’ test. We’re kicking that off in August, and then that will continue all the way through ’till we get to the launch site,” Arlen Biersgreen, AFRL’s program manager, said this week.

“So our launch right now is in early 2023; that will be at Cape Canaveral,” he added, noting that AFRL is working closely with Space Force Space and Missile Systems Center (SMC) and DoD’s Space Test Program on the launch, as NTS-3 will be sharing a spot on a Space Force launch.

The NTS-3, for Navigation Technology Satellite-3, project will test various elements of a possible new constellation of PNT satellites to complement, provide back-up — and, if all goes well, improve upon — the Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites operated by Space Force. It is one of AFRL’s top-priority Vanguard programs, which are aimed at speeding new capabilities to users, and as such is being developed in close partnership with the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center (AFLCMC) Agile Combat Support program element office.

The on-orbit demonstration will look at “resiliency in satellite navigation, as well as just robustness of the signal that we get from space,” Biersgreen said.

There are three segments to the effort, he explained: a space segment, i.e. the satellite itself; a receiver segment; and a ground control segment.

Going Commercial

The satellite — which will be about the size of an SUV, Biersgreen explained — is being built, and its subsystems integrated, by L3Harris Technologies under an $84 million contract granted in 2018. But rather than building a bespoke satellite bus to house AFRL’s PNT payload, the company instead bought a generic commercial bus from Northrop Grumman.

That bus, called an ESPAStar-D spacecraft, uses an Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) Secondary Payload Adapter (known as an ESPA ring), allowing multiple separate experimental payloads to be stacked together on one launch vehicle, explains a July 1 Northrop Grumman press release announcing its delivery to L3Harris.

By using an off-the-shelf bus, L3Harris and AFRL can cut down manufacturing costs, Biersgreen said. UPDATE BEGINS. The total budget for the NTS-3 program (2015 through 2024) is about $250 million counting launch integration and support through the Space Test Program, he said. UPDATE ENDS.

“The idea behind the ESPAStar bus star is to take a commercial bus that can be married up to any number of different payloads through known and published interfaces — whether that’s for individual flyaway satellites that might get a ride to space and then pop off and do their own thing — or more like what NTS-3 is doing, [with] a payload that’s integrated onto that bus, but it’s not in a bespoke way, it’s taking the the published commercial interfaces from Northrop Grumman and using those as part of the payload development and design process,” he elaborated.

Resiliency

Another aim for NTS-3 is to demonstrate resiliency by showing that another orbital configuration can be utilized by PNT satellites, thus making adversary efforts to target them more difficult. NTS-3 will be based in Geosynchronous Orbit (GEO, some 36,000 kilometers above the Earth), rather than lower down in Medium Earth Orbit (MEO) where GPS abides.

Using GEO, Biersgreen said, will demo “a hybrid space architecture, to provide augmentation essentially to the GPS constellation itself.”

Notably, the Space Development Agency also is looking to demonstrate PNT satellites in Low Earth Orbit (LEO, below 2,000 kilometers) to provide capability when GPS is denied; DARPA has a LEO PNT payload as part of its Blackjack program; and even the Army is experimenting with alternate PNT payloads in LEO.

“Gangsta” Radio

The receiver, or radio, is being designed primarily by AFRL, using a design developed Mitre Corporation and AFRL’s Sensors Directorate specifically for “doing prototyping and experimentation for satellite navigation signals,” said Joanna Hinks, NTS-3 principal investigator. It allows AFRL’s testers to receive both legacy GPS signals and the more advanced signals being generated by NTS-3, she explained.

GNSSTA — hilariously pronounced “gangsta,” but sadly not coming with a theme song by Dr. Dre — not only “picks up the signals, but does processing on them,” Biersgeen added. “It gives us both performance data as well as scientific data that we need to complete the experiments.”

Those advanced signals in part are seeking to overcome some of the vulnerabilities in the current GPS system. This includes using higher power to blast the navigation signal through the white noise a jamming system creates. It also includes signal and frequency “hopping” to keep in front of jamming.

“They are flexible and reprogrammable signals, so advanced satnav signals, [are] going beyond anything that GPS transmits today,” Biersgreen said.

Overcoming The Valley Of Death

The big question, of course, is what happens after NTS-3 is launched, and presumably does what it’s supposed to do successfully during AFRL’s planned year of on-orbit testing. And that, at least for the moment, remains a bit up in the air.

However, explained 2nd Lt. Charlie Schramka, the program’s deputy principal investigator, NTS-3 won’t just be shut down after the test year ends.

“The satellite is built to survive more than just a year in space, so we’re not just gonna throw it away,” he explained. “Once our year is up, we have this phase that’s called ‘residual use’ — sometimes called residual operations, although we don’t really like to throw the word operations around because that gets too confused with, you know, actual military operations, and that’s not really what we are; we’re an experiment — but the point of that is you can transition it to a different organization.”

In other words, another part of the Air Force or even a Combatant Command could use the NTS-3 to undertake experiments directed at warfighting capabilities or concepts of operations. But exactly who has yet to be determined, he said.

“Undoubtedly, that partner would be a Space Force organization,” Biersgreen said. “But we’re still working, both within SMC and also with headquarters Space Force, to determine who that might be, and what the goals of that two-year period would be and where the funding would be coming from for it.”

Space Force’s Saltzman: New readiness model ‘fundamentally alters’ space combat prep

The new, tripartite Space Force Generation readiness model will create “a more experienced, capable, and threat-focused crew force,” according to an internal memo obtained by Breaking Defense.