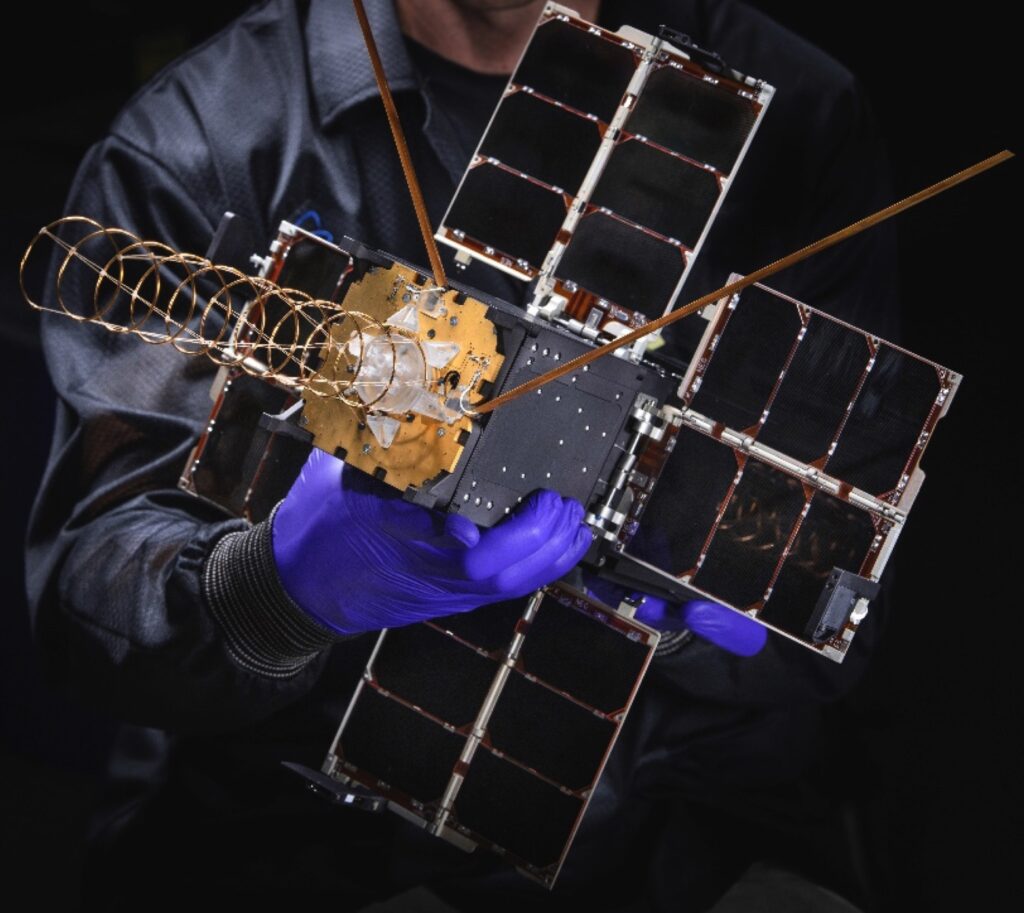

Gunsmoke-J experimental satellite. (Army)

WASHINGTON: The Army plans to continue to experiment with small satellites as a way to inform requirements for future long-range strike capabilities, according to Rick De Fatta, director of the Army Space and Missile Defense Center of Excellence.

However, in remarks to the Space and Missile Defense Symposium in Huntsville, Ala. yesterday, he took pains to stress the Army’s current mantra that it does not want to build and operate its own satellites.

“We do not intend to fly satellites in the Army,” De Fatta said. “While we intend to experiment, and are experimenting, with a small sats … once we’ve proven that technology, we will pass that back into these emerging architectures” being put together by the Space Force and Space Command, he explained.

Fatta’s center, one of 12 Army Centers of Excellence, is part of the service’s Space and Missile Defense Command (SMDC), which now serves as the Army Component Command to both Space Command and Strategic Command, as well as providing support to Northern Command for its missile defense mission.

His particular center is responsible for developing space and missile requirements, based on needs outlined by the Army’s related Cross Functional Teams (CFTs), he explained. Those requirements, in turn, drive development activities. In addition, De Fatta noted, the center is responsible for space and missile related science and technology research.

Space-based capabilities, he explained, will be crucial to the Army’s top-priority effort to conduct what it calls long-range precision fires — a requirement that the service sees as critical in any future conflict with China and/or Russia.

Indeed, joint long-range strike is one of the key tenets of the DoD’s new Joint Warfighting Concept, that in turn lays the foundation for the new American way of war, All Domain Operations. (And the Army’s plans to implement joint fires, including the development of super-long-range ground-based hypersonic missiles, are a bone of contention with the Air Force.)

“If you’re going to have long-range precision fires, you have to have long-range precision targeting. I will tell you, that implies that for extended ranges, you’re probably going to have to go to a space-based kind of sensor, and, you have to have a very mature sensor-to-shooter architecture,” De Fatta said.

De Fatta stressed that the Army considers space operations to be an integral part of its tactical mission sets.

“I will tell you the Army’s at a significant inflection point for space, and I emphasize space, moving out with formations and capabilities that transform from SMDC centric … the tactical Army and integrating it with our tactical formations. It’s exciting times for us. Army senior leaders understand space now and are demanding that capability,” he said.

The Army’s insistence that it must keep control of its own space operations has put it on a collision course with the Space Force, as well as the Intelligence Community. (In addition, the Space Force is in its own tussle with the National Reconnaissance Office and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency over where responsibility for space-based battlefield intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance lies.)

The issue at stake for the Army is who gets to call the shots about “tasking” — that is, where satellites are pointed and when, based on whose priorities. This question of tasking, in fact, is the key reason for the Army’s long-running campaign to find a way for it to use small satellites for ISR, either its own satellites or, as currently planned, to put its own ISR payloads on either commercial or other national security satellites.

In essence, experts believe, the Army simply doesn’t trust anyone else to give them the ISR information commanders need, when they need it.