An Unmanned Aerial System is prepped during PSC21. (Marita Schwab/US Army)

YUMA PROVING GROUND, Ariz: Soldiers are packed into a UH-60 Black Hawk flying to their objective. A small drone carrying ISR sensors launches off the side of the helicopter, buzzing off to scout ahead. The drone streams back a live video feed to the pilots and alerts them to an enemy threat on the ground.

The pilots communicate the threat information to other Black Hawk pilots transporting troops, and the fleet quickly changes its route. As the Black Hawks land at the objective, cameras on the outside of the choppers send live videos to soldiers’ augmented reality goggles, giving them a look outside before they even dismount.

This scenario from the Army’s Project Convergence, an annual experiment in connecting sensors and shooters that wrapped earlier this month, showcased potentially life-saving and battle-winning equipment — all of which rely squarely on resilient, uninterrupted and invisible network connections to pass all that data back and forth.

But like air dominance, that healthy network is far from assured in future conflicts, especially if it comes under electronic attack from Russian or Chinese forces. That’s why, amid testing more than 100 new technologies, Army leaders in the desert recognized the network itself as the backbone of future conflicts and have started grappling with the realities of the coming battle over bandwidth.

Read more: At Project Convergence, Army ‘struggling’ to see joint battlefield as it heeds ‘hard’ lessons

“One of the challenges that we saw out here is really the network and bandwidth. What information do you want to pass because you do have limited bandwidth?” Lt. Col. Dave Olsen, operations officer with the Next Generation Combat Vehicle Cross-Functional Team, said at the close of the exercise Nov. 9. “So working on those efficiencies of communicating data quickly, but also not overwhelming the network… that’s always going to be something we’re going to have to build on.”

The network, according to co-lead of the PC21 operational planning team Col. Andre’ Abadie , “is the center of gravity… The network is the critical path forward for the joint force.”

At Yuma Proving Ground, the Army toyed with different types of data packages, resilient waveforms to withstand interference, battlefield data management tools to strengthen links between joint force systems in combat and network extensions tools to connect ground assets to help in the air or even low-earth orbit. This year’s Project Convergence saw 27 sensor-to-shooter links accomplished, 21 more than last year.

“It was very clear to me coming out of this that the network is really going to be foundational at making sure that we can have [an] assured, reliable, resilient network underlying all of the systems that we’re using,” Secretary of the Army Christine Wormuth told reporters at the exercise’s media day.

So as the service continues to make tough decisions on budget decisions, Wormuth specifically pointed to the network and as well as assured precision, navigation and timing (APNT) technology, as capabilities the Army will need to protect.

“As I think about the budget, I’m thinking about those are capabilities, I think, we know that we’re going to have to make sure that we have resources for,” Wormuth said.

When High-Def And ‘Oversharing’ Is A Problem In Battle

As the military moves forward with the concept of Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2), in which joint force sensors and shooters are linked, the military must be able to pass data to a sister service’s sensor. This year’s Project Convergence provided a forum for all the military services to experiment with integrating disparate warfighting systems — and they found out how hard it can be.

But beyond integration, and with jets flying overhead, soldiers on the ground and ships at sea — all passing data between each other — the military will have to optimize its use of network bandwidth to keep critical information moving smoothly.

Read more: Lack of future helo doesn’t stop Army’s Future Vertical Lift experiments in the desert

For instance, the air assault scenario using the augmented reality goggles, formally called the Integrated Visual Augmentation System, was the first time the service successfully shared “stabilized video” between aircraft using IVAS. But it revealed pointed network issues, according to Travis Thompson, deputy director for the Soldier Lethality-CFT.

“If you want high fidelity, that’s large bandwidth — and was that more valuable than just a picture?” Thompson said. “A picture in many cases did the exact same thing, [it] could go through at a higher resolution, inform the decision better. But we … were going video.”

As the service ran those types of experiments, it started “being smarter,” Thompson said. “We learned that different wavelengths and which way we share that information also allows us to either move faster, or to inform that decision in a better way.”

Cross-functional teams working together also encountered network issues during an experiment involving Future Vertical Lift Cross-Functional Team (FVL-CFT) and NGCV systems, connected by a small drone. In that case some assets were “oversharing and causing problems [and] taxing our network unnecessarily,” according to Network-CFT Chief of Staff Col. Eric Van Den Bosch.

Maj. Gen. Wally Rugen, director of the FVL-CFT, echoed Van Den Bosch during an October media day in Yuma, adding “those rates are important … and we’re playing with that so the data doesn’t just flood the network with superfluous things.”

The FVL team has worked on being more efficient with passing small data packages across the network since last year’s Project Convergence. Those packages can now be sent automatically, but still required some refining at this year’s event.

“They were real rough at first because of the multitude of players here on this network and so there was some complaints that it was a little grainy,” deputy director of the FVL CFT Jim Thomson said, referring to a picture of a target that was ultimately fixed. “So we now have a really good baseline to write a requirement based on what we learned over the last 18 months.”

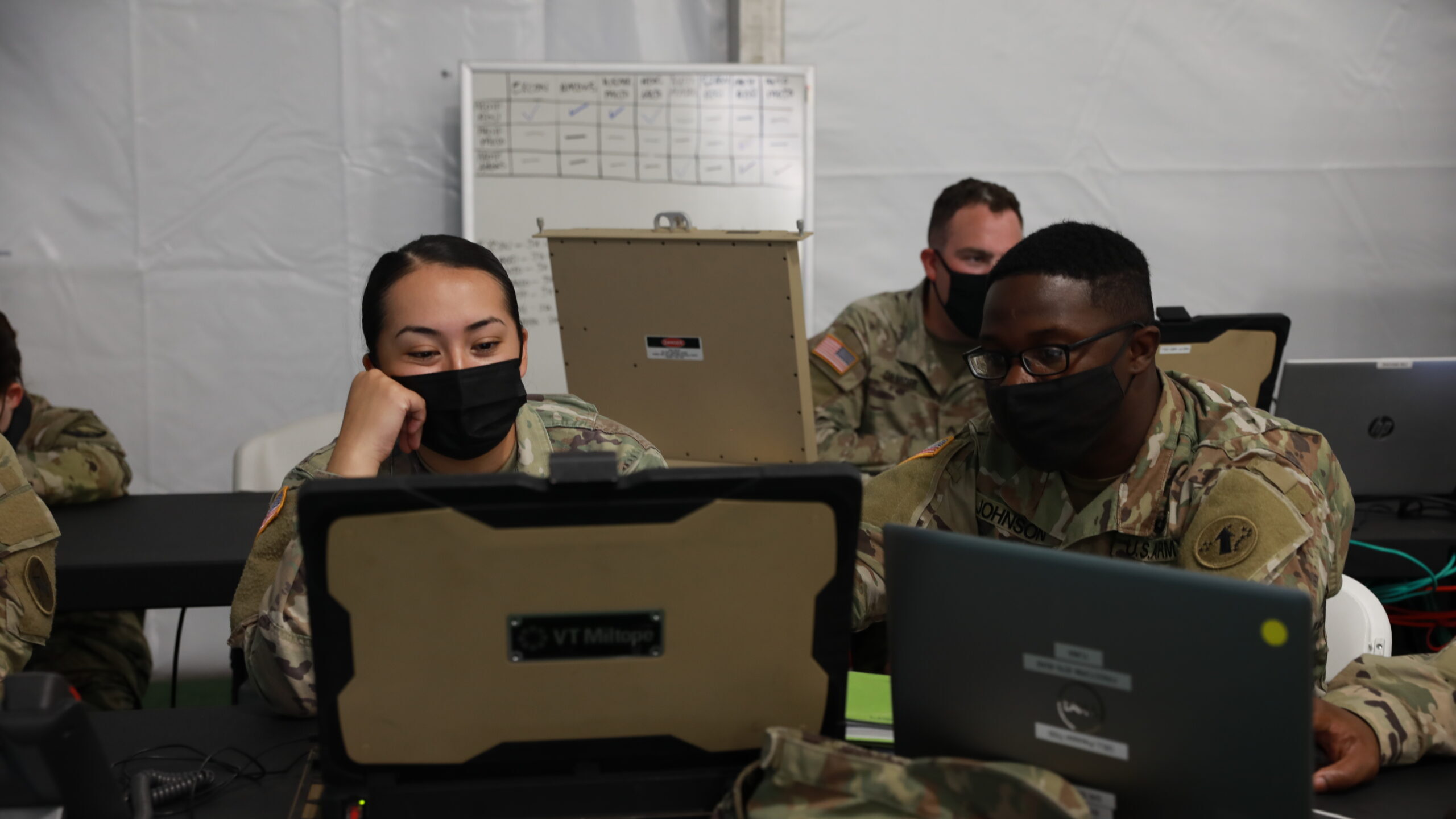

Network capabilities were a big part of PSC21. (Destiny Jones/US Army)

As efforts move forward, the Network Cross-Functional Team’s common data fabric, known as Rainmaker, may be able to help sift through and route data. Merely in the proof of concept phase last year, this year Rainmaker integrated Army and Air Force systems, merging data from disparate mission command systems.

According to Lt. Col. Stephen Kirchhoff, air to ground lead and lead network planner for PC21, as the technology further matures, the data fabric and artificial intelligence could be used not only to integrate the data, but to prioritize it so both the network and commanders aren’t overloaded with information.

“They’re not going to need to know the location of your Alpha team leader on the ground,” he said. “But as we connect sensors to these edge networks, if something senses a high priority target that piece of information probably is relevant to the division commander. So the challenge becomes how do you identify what information needs to go from edge up through echelons so that the relevant data is getting to your division commander.”

Leveraging Air And Space For Network Help

While Project Convergence stretched emerging technologies to its limit, the 82nd Airborne Division brought its new Integrated Tactical Network gear that connects ground troops across the battlefield using new hardware such as radios, waveforms and small satellites terminals. The experiment showed that that gear works against simulated adversary threats at Project Convergence.

“One of the biggest things that we’ve taken away from this is that the Integrated Tactical Network is very robust. It’s living up to what we thought it would be,” said Maj. Gen. Chris Donahue, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division. “I think it’s a very capable network to go forward as we continue to develop.”

But should ground-based systems fail or come under attack, the Army is looking upwards to provide network extension capacity and other communications options when jammed. Using small long endurance drones, for instance, the FVL-CFT tripled the length of its network from PC20. Those drones will be a useful tool over the vast distances of, say, the Indo-Pacific.

“Aerial platforms — if they’re in kind of a dedicated communications relay role — we’ve shown that they can extend the mesh network out to greater distances [and] provide greater coverage,” Kirchhoff said.

Maj. Gen. Christopher Donahue, commanding general of the 82nd Airborne Division. (Emily Opio/US Army)

This year the service also saw improvements in coverage from satellites in low-earth orbit, with just a few minutes available during last year’s event to near 24/7 coverage of Yuma Proving Ground, according to Van Den Bosch. The addition of LEO satellites to provide another networking route promises higher throughput and lower latency because they are positioned closer to the earth.

Van Den Bosch said the service successfully demonstrated the ability to automatically “fail over” to an uninterrupted SATCOM path in mid-Earth orbit or geostationary orbit, a valuable communications capability for a jammed environment.

“There’s opportunity to move forward, to keep the gas on, bringing that capability to the fore,” Van Den Bosch said. “So we’re looking for opportunities to partner with operational units to gain more information, how they can leverage those satellite constellations and then come back to PC22 and learn more.”

Overall, Army leaders said this year’s Project Convergence was successful in that it identified weaknesses in its current strategies, from network resiliency to successfully integrating all the data that does come through the network to understanding just how mindbogglingly complex the future battlefield may be.

Next year’s Project Convergence, which is expected to involve US allies as well, promises even more complexity.

“What may not be a problem for the Army may be a problem when it goes to the Air Force or vice versa,” Thompson said. “We’re having to learn that on a much larger scale next year with coalition forces.”