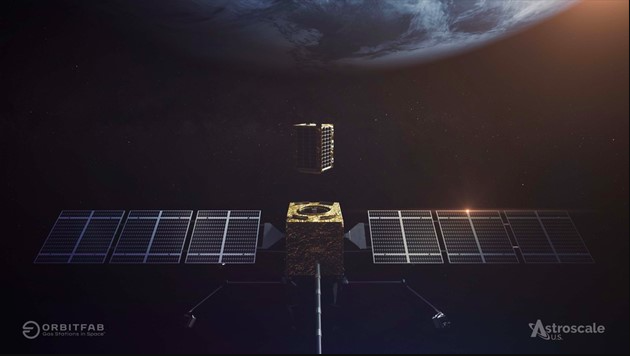

Astroscale will refuel its satellite servicing spacecraft using Orbit Fab’s ‘gas stations’ in space. (Astroscale/Orbit Fab concept art)

WASHINGTON: The US arm of Japanese firm Astroscale has inked a deal to be the first customer in line to refuel at San Francisco startup Orbit Fab’s planned “gas stations” in Geosynchronous Orbit (GEO). Meanwhile the firm is gearing up its own pitch to the Space Force’s SpaceWERX innovation hub for cleaning up space junk.

Under a new contract, announced today, Astroscale is outfitting its new Life Extension In-Orbit (LEXI) Servicer spacecraft with Orbit Fab’s Rapidly Attachable Fluid Transfer Interface, or RAFTI — think of an aircraft refueling boom designed for space operations — that enables any spacecraft to dock with Orbit Fab’s orbiting fuel tanks.

LEXI, which is expected to launch in 2026, will provide “station keeping and attitude control, momentum management, inclination correction, GEO relocation and retirement to graveyard orbit” to satellite operators (commercial, civil and/or military) looking to keep ailing satellites functioning or to safely dispose of dead ones, according to the companies’ joint press release.

However, Ron Lopez, president of Astroscale US, Inc., told reporters Monday, LEXI it will not provide refueling — that instead, he said, will be Orbit Fab’s job.

“By purchasing fuel from Orbit Fab, that will allow Astroscale’s LEXI servicers to be more flexible, more efficient and extend the capabilities of what we can do, and provide better value-added services to our customers at Geosynchronous Orbit,” he said. “That in turn ultimately enhances our value proposition to the customers, and customers will benefit from that as well. So having more options is always good thing.”

“We commit to delivering fuel and Astroscale commits to buying that fuel,” explained Daniel Faber, Orbit Fab CEO, in the press briefing. The contract, for an undisclosed amount, is “the first contract in the industry of its kind,” although such pre-agreements are “very common” in other commodities industries, he said. “We’re very happy to be bringing this business model to the space industry.”

RAFTI, too, is a first-of-its-kind satellite fueling and docking interface, which customers will need to fit to their spacecraft to be able to use Orbit Fab’s refueling shuttles.

“At the moment, it’s the only commercially available [system] for refueling satellites in orbit. We are selling and shipping those to customers. So there’s no other options at the moment for refueling satellites,” Faber said.

Orbit Fab launched the first-ever fuel depot to Low Earth Orbit (LEO), taken up aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 on June 30, 2021. The depot, called Tanker 001 Tenzing, stores the green propellant High-Test Peroxide (HTP) in a sun-synchronous orbit to refuel other spacecraft, according to the company’s website.

Faber said it plans to launch its first depot to GEO “by the end of the year.” That depot will store Xenon, commonly used by satellite maneuvering thruster, he added.

Faber said it plans to launch its first depot to GEO “by the end of the year.” That depot will store Xenon, commonly used by satellite maneuvering thruster, he added.

According to the two firms’ joint press release today, Orbit Fab is planning “dozens of fuel tankers and shuttles in the next 5 to 10 years, positioning them in proximity to customer satellite constellations in low Earth orbit (LEO), GEO and cislunar space.”

“In cislunar, we’re responding to customer interest on that, and there is some,” noted Faber.

Indeed, Space Force and Space Command have become increasingly interested in expanding US military operations to the vast volume of cislunar space from Earth’s outer orbit to that of the Moon, and even beyond to, well, infinity.

Space Force in particular sees active debris removal (ADR) as a as a first step to opening the market for on-orbit service, assembly and manufacturing (OSAM) — a set of capabilities foundational to that capability. To that end, SpaceWERX’s newly opened Orbital Prime contest is aimed at accelerating development of new dual-use tech for ADR.

Asked by Breaking Defense whether Astroscale US would throw its hat in the Orbital Prime ring, Lopez said: “The short answer is yes.”

“We believe that Astroscale’s technology and capabilities we’re demonstrating now, and will continue to demonstrate the LEXI and other programs, as well as the experience that our leadership team brings both here and [the company’s arm] in Israel in terms of designing and delivering programs, delivering solutions to customers makes us a strong competitor,” he added.

Orbit Fab, too, is eyeing Astroscale’s ADR services as part of its own multifaceted efforts to ensure that its fuel depots don’t become giant bombs in space from impact with space junk, Faber said.

“We’ve been talking with Astroscale about the possibility of deorbiting … if there’s any problem with the tanker,” he said. “We think that is the way of the future — that these things will be actively removed and preferably recycled, but those business models need to find their feet yet.”

Discarded rocket bodies still containing fuel are in fact among the biggest contributors to the ever-burgeoning population of hundreds of thousands of pieces of dangerous space debris. Thus, a key tenet of the UN Guidelines on Debris Mitigation, as well as the US guidelines developed by NASA, is for operators to jettison any leftover fuel from spent rocket bodies.

Faber said that Orbit Fab has been testing the capability to dump fuel and maintain tanker pressure on its LEO-stationed fuel depot as a key safety measure.

“Those are passive systems that don’t rely on active electronics in case there’s any faults. So that’s all working quite well,” he noted. Further, the depots have thrusters aboard that will allow them to move out of the way upon warning of a likely collision.

“We do not intend to create any harmful debris in any orbits that matter,” Faber stressed. “And that’s quite important to how we do things.”

HASC chair backs Air Force plan on space Guard units (Exclusive)

House Armed Services Chairman Mike Rogers tells Breaking Defense that Guard advocates should not “waste their time” lobbying against the move.