A Ground-based Interceptor missile, an element of the nation’s Ground-based Midcourse Defense system, launched from North Vandenberg Sept. 12, 2021. (U.S. Space Force photo by Airman Kadielle Shaw)

WASHINGTON: A new study of US missile defenses has found that — after 70 years and some $350 billion in investment — no “system thus far developed has been shown to be effective against realistic ICBM threats” to the homeland. It’s a conclusion with which the Pentagon’s Missile Defense Agency begs to differ.

The study by the American Physical Society (APS) examined a hypothetical North Korean strike and current missile defense systems, such as ground-based interceptors, as well as more futuristic options in development, like directed energy weapons and space-based interceptors. It found today’s capabilities inadequate and future systems unlikely to do the job of defending the country in the next 15 years at least — even from a small number of North Korean missiles.

“Creating a reliable and effective defense against the threat posed by even the small number of relatively unsophisticated nuclear-armed ICBMs that it considers remains a daunting challenge,” the Feb. 9 APS report, called “Ballistic Missile Defense: Threats and Challenges” finds.

APS is a non-profit membership organization for physicists and scientists in related fields, founded in 1899. The study was conducted by a panel that includes a number of scientists who are known for their support of nuclear arms control. The panel was chaired by Frederick Lamb, a physics professor at the University of Illinois who has had a long career in national security and arms control, including advising the Defense Department.

RELATED: North Korea’s hypersonic missile claims are credible, exclusive analysis shows

“The difficulties are numerous, ranging from the unresolved countermeasures problem for midcourse-intercept to the severe reach-versus-time challenge of boost-phase intercept. Few of the main challenges have been solved, and many of the hard problems are likely to remain unsolved during, and probably beyond, the 15-year time horizon the study considered. The costs and benefits of this effort therefore need to be weighed carefully,” the APS study concludes.

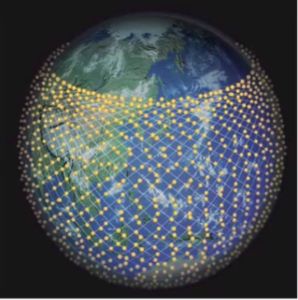

In particular, the study asserts that directed energy weapons for intercepting intercontinental ballistic missiles early in their flight will not be ready for prime time within that 15-year period. As for space-based interceptors (SBIs) — a concept revitalized during the Trump administration — the study finds that hundreds of on-orbit platforms would be needed to shoot down only one of North Korea’s least capable ballistic missiles.

Officials from the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) contested the study’s conclusions, however, pointing Breaking Defense to the most recent report [PDF] by the Pentagon’s top testing official, the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E). That report found that, taken together, the various missile defense programs are capable of doing what they are designed to do.

“The Missile Defense System (MDS) has demonstrated a measured capability to defend the United States, deployed forces, and allies from a rogue nation’s missile attack,” the DOT&E report said.

(APS graphic)

The More Things Change…

Many of the APS report’s findings echo those of a number of studies by outside scientists over the past two decades. In addition, the Government Accountability Office does an annual audit of the all the missile defense elements that consistently has cited a lack of sufficient testing across many of the various missile defense efforts.

Essentially, APS finds: plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Despite large and continued investment, missile defense programs have not been fully proven as capable of protecting the US from ICBMs.

In the same vein, Missile Defense Agency officials, industry representatives and advocates for missile defenses over the years have made their own consistent arguments: that these external studies have relied on outdated and, because of classification restrictions, inaccurate data. They also consistently have pointed out that there are constraints on realistic testing for a number of reasons such as safety, and that testing parameters have been more than sufficient to prove capability.

In response to questions from Breaking Defense, MDA officials last week stressed that senior US military leaders in recent years have pronounced the current homeland missile defense system as fully ready and capable against a North Korean attack — including Strategic Command head Adm. Chas Richard, Northern Command head Gen. Glen VanHerck and former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. John Hyten.

Most recently, VanHerck told reporters at the Pentagon in September that if North Korea were to launch a missile, NORTHCOM is “ready 24/7, 365,” adding “I’m confident in our capabilities.”

But in a Feb. 16 webinar on the findings, Lamb asserted “that our report has been able to use very up to date and current information, and all information that you need to make a decision about these kinds of general technological and policy questions.”

The 56-page study specifically looked at the two scenarios that might be considered minimum viable attacks — “what would be required to defend against the launch of a single ICBM from North Korea, or the salvo launch of 10 in rapid succession, taking into account countermeasures North Korea may be able to use to penetrate U.S. defensive systems.”

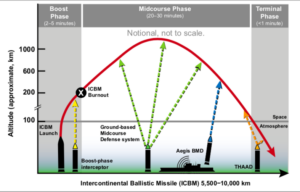

It considered the capabilities of the US Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system; the planned Next Generation Interceptor (NGI); the Navy’s ship-based Aegis system originally designed to intercept short-, medium-, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles that is now being considered for midcourse-intercept of ICBMs; the Army’s Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system; and potential boost-phase systems using either hit-to-kill or directed energy. The study found issues with each.

GMD: Effectiveness ‘Likely To Be Low,’ Study Co-Author Says

“Due to its fragility to countermeasures, and the inability to expand it readily or cost-effectively, the current midcourse intercept system cannot be expected to provide a robust or reliable capability against more than the simplest attacks by a small number of relatively unsophisticated missiles within the 15-year time horizon of this report,” the study says.

Laura Grego, Stanton Nuclear Security Fellow at MIT’s Laboratory for Nuclear Security and Policy and a co-chair of the study, explained during the webinar that Ground-based Midcourse Defense’s “effectiveness in battlefield situations is likely to be low” based on its lackluster testing results over the past 20 years, despite testing parameters being skewed in favor of success. This includes, for example, the use of decoys to simulate adversary countermeasures designed to be brighter than the target missile’s warhead to simplify the interceptor’s ability to discriminate between them.

“Even so, the system has failed as often as it has succeeded,” she asserted. “In the 19 tests conducted since 1999, the interceptors were successful in destroying the targets in 10 of these. The Pentagon has consistently rated the GMD tests as low in operational realism. Only the last few tests have used the warheads of ICBM range missiles as targets; and it is yet to be tested against a salvo of attacking missiles, meaning more than one.”

In response, MDA spokesperson Robert Carver told Breaking Defense that since 2017, “the GMD system has been tested twice in operationally realistic scenarios against ICBM target threats. These tests used a total of three Ground Based Interceptors against two ICBM target missiles and successfully intercepted both.”

Carver said it was “important to note” that in those cases the ICBMs used countermeasures designed to thwart the ground-based interceptors, “which were still able to identify the Reentry Vehicles (the ICBM target missile warhead) and successfully destroy both.”

DOT&E also pronounced GMD as fit for purpose in the January report. The system “has demonstrated the capability to defend the U.S. Homeland from a small number of ballistic missile threats with ranges greater than 3,000 kilometers and employing simple countermeasures, when supported by the full architecture of Missile Defense System (MDS) sensors,” the report said.

NGI: Still In Development As MDA Aims For 2028 Operations

MDA intends to supplement (not replace) the current arsenal of 44 GMD interceptors with 21 Next Generation Interceptors, as well as build another 10 for testing, with a life-time price tag of $18 billion, Grego explained. She noted that “if rigorous engineering procedures are followed” by MDA prior to fielding, “some of the previous design and reliability problems” that have plagued GMD can be avoided.

“However, even if those improvements are made, the issue of effectively discriminating warheads from decoys remains unsolved,” she added.

Carver stressed that NGI, which was initiated to counter North Korean advancements in missile tech, is still in development. “NGI will meet warfighter operational need for accelerated emplacement” no later than the fourth quarter of fiscal 2028, he said.

Due to the laws of physics, numerous space-based interceptors would be required to hit one incoming ballistic missile, according to a new study by the American Physical Society. (APS graphic)

Boost-phase Interceptors: Long Time ‘Til ‘Technically Feasible’

The study concludes that “all these systems,” whether based on land, at sea, in the air or in space, “would face very difficult technical challenges” and “be unable to defend the entire continental United States.”

In particular, Lamb told the webinar, laser weapons for boost-phase intercept “based on aircraft, drones or space platforms will not be technically feasible within the 15 year time horizon of this study.”

Further, he said, a space-based interceptor system would require “at least 400 orbiting interceptor platforms” to counter a single, liquid-fueled North Korean missile; and to counter 10 such missiles launched within a short time period, “at least 4,000.” And because solid-fueled missiles are “more demanding” a challenge, he said, intercepting just one would require 1,600 SBIs.

Victoria Samson of the Secure World Foundation applauded the work on SBIs, noting that the study had been careful to take into account technology developments over the past two decades.

“I know that boosters of SBI would argue that the launch costs have improved so much that the limitations brought up in the older studies are no longer relevant, but this is not the case,” she said in an email. “The physics is still the same: if we want coverage of a specific region, orbital mechanics requires a certain number of interceptors on orbit to ensure that that coverage is provided.”

While MDA continues to research directed energy, along with the military services who are bullish on the promise of using lasers to counter drones, the agency’s director, Vice Adm. Jon Hill, has actually expressed caution himself about applying them to boost-phase intercept. “I think it’s pretty far away,” he told the Heritage Foundation in 2020, according to a report in Defense Daily.

In a ‘world first,’ DARPA project demonstrates AI dogfighting in real jet

“The potential for machine learning in aviation, whether military or civil, is enormous,” said Air Force Col. James Valpiani. “And these fundamental questions of how do we do it, how do we do it safely, how do we train them, are the questions that we are trying to get after.”