When talking about nuclear policies and programs, defense leaders often emphasize that “the Cold War is over.” But given a chance to explain what is strategically different and how policies and programs need to be changed, they duck and cover.

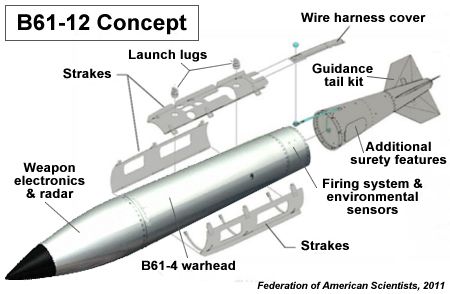

Take, for example, a recent congressional hearing on the B61 nuclear bomb. The Defense and Energy Departments want Congress to approve plans for rebuilding the weapon, principally to replace its four remaining variants with a single new model, called the B61-12.

If deployed with the addition of a tail kit assembly from the Air Force, the new version should be more accurate and have a “modest” standoff capability. There has been no official statement of anticipated yield, but observers anticipate a variable yield similar to that of the B61-4 (.3 to 50 kilotons).

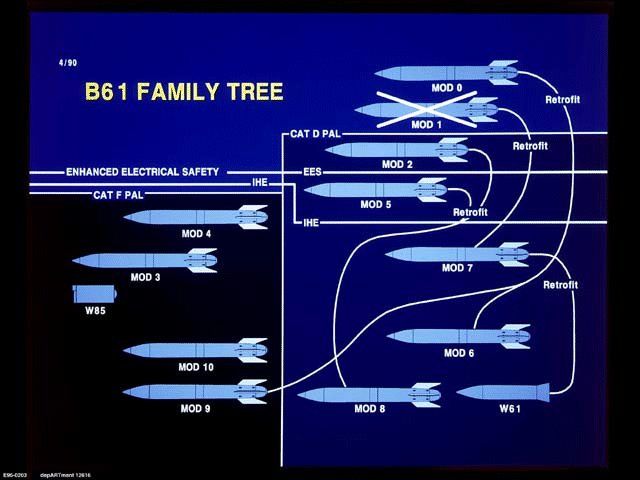

The B61 is made to order as a case study of in-depth deliberations about post-Cold War nuclear policies and programs. Since entering the inventory in 1966, the weapon has been modified into several versions, most of which are capable of being dropped from several types of fighter and bomber aircraft. The different weapons deliver yields reportedly ranging from .3 kilotons to about 340 kilotons. B61 has been the material embodiment of the US nuclear commitment to NATO. During the Cold War it was intended to be used both to blunt a large conventional attack by the Warsaw Pact and to trigger escalation to intercontinental nuclear war. Since the Cold War it has remained in Europe, in reduced numbers, perhaps due more to alliance politics than requirements of deterrence.

As the only nuclear weapon of any nation currently publicly declared to be deployed on foreign soil, the B61 compels attention particularly to issues of extended deterrence; regional conflict management; allied autonomy; regional targets we might want to hit with nuclear weapons; and how our nuclear forces should be postured for what we might want to do vis-à-vis much smaller nuclear enemies, such as North Korea, Iran, or some non-state entity without entangling larger nuclear powers.

But in testimony before a supportive congressional subcommittee, the witnesses steered clear of exploring those issues, making only a few brief references to the bomb being part of the American deterrent and an option that some future president might use. The testimony focused instead on supporting a particular option for B61 modernization, emphasizing that the rebuild was key to reducing the variety and total number of weapons in the stockpile and that their preferred approach would save money in the long run. A follow-up letter from the Secretaries of Defense and Energy followed the same line, although a careful reading does suggest how much has to happen before the purported savings and arms reductions come into view.

Perhaps the testifiers and letter-signers knew that the committee was only interested in hearing support for one modernization option. Or maybe they thought the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review provided all the strategic rationale that was needed. Whatever the case, it seems short-sighted to pass up a chance to expand the strategic dialog. Most B61 variants are “non-strategic” but the reasons for them should not be: there are many more decisions to be made and revisited before the future US nuclear posture is settled.

Why will the B61 be important to future US national security? Three reasons come to mind: credibility, demonstrability and repeatability.

Credibility: The B61 probably will be the only actively deployed weapon suitable for use in a regional conflict where there are targets requiring nuclear attack for at least several years. While target requirements for yield and delivery options depend on circumstances, the gravity bomb’s combination of lower yield and higher accuracy promise lower collateral damage than would result from using missile-delivered nuclear warheads.

Demonstrability: Because it can be forward deployed by different aircraft, the B61 is well suited for compellance operations, efforts to get adversaries to stop doing something or to undo something already done. Particularly for crisis management, compellance operations are central to maintaining US “extended deterrence” relations.

Repeatability: US nuclear weapons are legacies of the Cold War. They comprise warheads that were not designed for, and are not particularly appropriate to, scenarios and targets expected in war against small nuclear powers. US policies have been understood to constrain work to design weapons that might better address new requirements. Success with the B61-12 might encourage other modernization efforts that could make part of the legacy stockpile less inappropriate.

Each of these presumed advantages, of course, needs to be considered within a broader strategic framework. It took time and effort to understand the role we wanted nuclear weapons to play in our Cold War strategy; we face a similar challenge now, and we should not miss opportunities to advance the dialog. Simply changing some legacy procedures and chasing further reductions in numbers of weapons will not do the job. As Kissinger saw in 1957, “in the absence of a generally understood doctrine, we will of necessity act haphazardly . . . . Each problem, as it arises, will seem novel, and energies will be absorbed in analyzing its nature rather than in seeking solutions.”

Bob Butterworth is a consultant and expert on nuclear issues and intelligence. The president of Aries Analytics, Butterworth was former senior advisor to the head of Space Command and was a staffer on the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, as well as on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.