Russia casts a long shadow nowadays, especially if you’re a neighbor. Armed with heavy tanks, jet fighters, long-range missiles, and the world’s slickest state-sponsored cyber-criminals, Russia is a very different threat from the so-called Islamic State, the Taliban, or even China. So how must the US and its NATO allies change gears, mindset and tactics to cope?

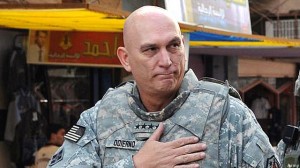

Gen. Ray Odierno

Last week, I got to ask three 4-star generals just those questions: the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, Air Force Gen. Philip Breedlove; Breedlove’s senior air commander, Gen. Frank Gorenc; and Army Chief of Staff Gen. Ray Odierno. The evolving answer, they said, is neither a “back to the future” revival of Cold War tactics nor a continuation of the last 13 years of counterinsurgency, but a hybrid that draws on both. In essence, we have to scale up the sophisticated command, control, and coordination we’ve learned over the last decade to handle the sheer size and intensity of a European war.

“It’s a combination,” Gen. Odierno told me. It’s not a matter of “unlearning” any lessons from the post-9/11 wars, he said, but rather “adapting.”

Gen. Philip Breedlove

“It’s a good news story,” Gen. Breedlove said. “The good news is yes, there has been a different kind of mission, but what we have gained across the last 10 to 12 years is incredible interoperability.”

“We’ve worked through a lot of the kit problems” that kept different countries’ aircraft, command posts, and networks from sharing information, Breedlove explained, meeting me in civilian clothes after the Air Force Association conference had ended for the day. But it’s not just the technologies that work better together now, he said, it’s also the humans: The NATO allies have had “10 to 12 years of sharing, practicing, and employing tactics, techniques, and procedures that standardize us across the force.”

Working together didn’t mean dumbing it down, either, Lt. Gen. Gorenc had told me earlier at AFA. “In Afghanistan, we’re doing operations at a very high level in the air, at PhD level,” he told me and another reporter at the conference. “The command and control required to do what we do inside the Afghanistan theater is absolutely spectacular. [The question is,] how do we bring back all of those spectacular things that we’re doing as an alliance in this command structure and inculcate it to the exercises that we do, so that all of these countries that now have developed skills can maintain them in the out years?”

Gen. Franc Gorenc

The alliance was looking at this training issue even before Vladimir Putin’s “little green men” took over Crimea. “Before even the revanchist Russia, this was one of our goals in NATO, one of the first goals I had,” Breedlove told me: “How do we reset NATO?” The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) mission in Afghanistan will finally end this year, though US and NATO advisors will remain. “We had in our plan for NATO post-ISAF changing our exercise structure such that we are going to look at that higher-end, Article V, kinetic type of fight,” he said, “but we start from a very solid base.”

“The mission is different, but the sharing of tactics, techniques, and procedures, the sharing of that interoperability… those things all transfer,” Breedlove summed up. And, he affirmed, there’s no amount of exercises back in Europe that could have taught NATO as much about working together as the real-life experience under fire in Afghanistan.

Interoperability isn’t a solved problem, however, Gen. Odierno warned me a few days later, as we walked out of a Defense Writers Group breakfast. “We’ve been working together in Afghanistan, we have interoperability in some ways, but because Europe has downsized their forces, the way we have to be interoperable is very different,” he told me Friday. “We have to do it at a much lower level, which makes it actually more difficult.” Small units don’t have the large staffs, powerful communications networks, or experienced senior officers that large ones do. That’s why the Army is deploying so many division headquarters it’s started running short of them, even though it’s no longer deploying whole divisions.

Experienced personnel are especially important because of what Odierno considers the most fundamental, universally applicable lesson of the last decade. Military means alone are not enough, he said: “It’s got to be a whole of government approach. It’s got to be a joint, interagency, multinational capability that deals with problems, including whatever problems they have in Europe.”

Even the “purely” military aspects have gotten more complex, said Odierno. Commanders must coordinate not just ground and air units from multiple nations, as in the 1980s doctrine of “AirLand Battle,” but also naval forces — which can now reach targets deep inland with precision-guided missiles — and, increasingly, space and cyberspace operations as well. A well-aimed virus, for example, could blind enemy air defenses long enough for friendly fighters to strike some target keeping US ground troops from advancing. Military doctrine calls these separate but constantly interacting spheres of activity “domains,” and, Odierno told me, “we have to start incorporating multi-domain warfare into NATO.”

Afghanistan and Iraq gave the US and its allies a chance to practice some of this complex command-and-control, but on a relatively small scale. After the initial invasions, the post-9/11 wars were largely fought by platoons and companies, not brigades, and by pairs of aircraft, not squadrons. A major war in Europe would involve divisions or corps maneuvering on the ground, Breedlove warned the audience at AFA, and “hundreds or even thousands of sorties a day” in the air.

Nor will the air be automatically ours to command. It would be in “contested airspace,” Gorenc said in his AFA talk. With the long ranges of the latest Russian anti-aircraft missiles, in fact, “today one-third of Poland is under Russian IADS [integrated air defense system] coverage,” he told the audience. “Today! And there are other parts of NATO airspace where that is also true.”

Gorenc didn’t name names, but if Russia’s anti-aircraft weapons cover much of Poland — a large country which only borders Russia in the tiny enclave of Kalingrad — then they must cover 100 percent of the three small Baltic states, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, which border the Russian motherland directly.

NATO needs to come to “the realization that we don’t have complete air dominance,” Gorenc told me and the other journalist afterwards. “We may have to either suppress or destroy enemy air defenses,” he said. “It’s not that we don’t have the skills, because we do, it’s just …. a mission that quite honestly we haven’t had to do a lot of.”

“We tend to take some things for granted, like air superiority,” Breedlove agreed. “In an anti-access/area denial environment” — aka A2/AD, the kind of layered long-range defense being built by Russia, China, and to a lesser extent Iran — “we would have to earn air superiority.”

In other words, we’d have to fight for it.

Russian “Beech” surface-to-air missile launcher.

That’s something US and NATO pilots haven’t had to do since the 2010 airstrikes on Libya, and there on a very small scale. There were so many anti-aircraft missiles around Baghdad in 2003 that Air Force pilots called the area the “super MEZ” (from “Missile Engagement Zone”), said Breedlove, but those were less sophisticated weapons and less well-trained crews than what Russia operates today. And in Iraq post-2003 and Afghanistan post-2001, the biggest anti-air threats have been Russian-made heavy machineguns known as Dushkas and the occasional shoulder-launched missile. Electronic warfare such as jamming, let alone cyber-attacks, was entirely beyond the enemy’s abilities.

“We built tactics around a permissive environment,” Breedlove acknowledged. “Now we’ll have to adapt those tactics to get through the initial stage of a battle, where we fight down the integrated air defenses, we establish air superiority, and then we can reinsert our more permissive tactics.”

Assuming we ever actually achieve air superiority, I said skeptically.

“We have the capability,” Breedlove said. “I lot of confidence in our troops.” Of all the differences between today and the Cold War, he said with a smile, one stands out most: “Let me tell you, be very clear, the young people today are far more lethal and far more capable than we were.”

Missile Defense Agency’s new long-range radar steps toward full deployment

“The LRDR completed a Space Domain Awareness (SDA) data collect event in January 2024 that proved the SDA capability, and the U.S. Space Force and MDA are in the process of formally declaring LRDR ready for SDA early use in April 2024,” according to MDA Director Lt. Gen. Heath Collins.