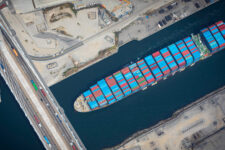

China’s new airstrip built over Fiery Cross Reef in the South China Sea (CSIS image)

UPDATED 9:45 am Tuesday with details of operation & Chinese response WASHINGTON: After five months of hints, declarations, mixed messages, and dithering, the US is reportedly set to challenge Chinese claims in the South China Sea.

But the months of signaling will cost us. What might have been a low-key “freedom of navigation operation” — sailing, flying, or training in disputed areas to set a legal precedent for access — may well get a lot more complicated because of the buildup.

“[I’m] still waiting to see it before I believe it,” one Senate staffer said. (The Pentagon declined to comment when we asked for confirmation). “It’s long overdue, and the long delay has made it a bigger deal than it actually is.”

[On Tuesday morning, local time, the destroyer USS Lassen passed by Subi Reef, accompanied by US surveillance aircraft].

“I do think we have paid a price [for delaying], mostly in terms of confusing everybody about why freedom of navigation operations take place,” said Bonnie Glaser, director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic & International Studies, who recently returned from her latest trip to China. “There are many people that I have spoken to in China who view this as a challenge to Chinese sovereignty, which it is not, or who view it as a provocation, which it also is not.”

“People in official positions” in China are reportedly saying that the People’s Liberation Army should open fire at US forces if they enter the 12 nautical mile zone around artificial islands in the South China Sea, said retired Navy Commander Bryan Clark. (Under international law, such manmade landmasses do not confer sovereignty on those who build them). World War III is not going to happen, happily, he said, but the bellicose talk shows how much pressure Chinese policymakers are under.

“The Obama administration has put themselves in a worse position strategically,” said Clark, now at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. “It was all because the US delayed.” Normal freedom of navigation operations are quiet exercises in setting legal precedents — we can sail through this area, we can fly here, we can conduct operations — but five months of public uncertainty has made this one a big deal, he said.

“The US could have done much better by simply doing the exercise without saying anything about it, and China could have responded probably at a much lower level,” Clark told me. Now, “it forces China to react in order to save face [and] be able to argue to their people they didn’t take this lying down.”

There’s an impact on China’s maritime neighbors, too. “They’re very watchful,” said the Heritage Institute’s Dean Cheng. “I think it probably came as more than a bit of a shock when Secretary of Defense Carter makes these very strong statements at Shangri-La in May,” Cheng told me. But then it becomes clear when Sen. John McCain pressed for an answer that the US hasn’t gone within 12 nautical miles of any Chinese-claimed territory since 2012.

At least one expert thinks the Obama administration has legitimate reasons for waiting, argued Patrick Cronin, director of the Asia-Pacific Security Program at the Center for a New American Security. Yes, they waited too long: “The White House should already have green-lighted a FONOP and should announce that the U.S. plans to conduct such operations as a matter of routine,” he told me, “but I recognize the White House is looking at the issue through a different lens from the Pentagon.”

Freedom of navigation operations in November could complicate the president’s visit to Asia that month, Cronin said, overshadowing the rest of his agenda and making it harder to get Chinese cooperation on issues from cyber espionage to trade. Sailing or flying within the 12nm limit in September could have scuttled that month’s summit with Chinese president Xi Jinping. Earlier this summer, the administration was working hard on the Trans-Pacific Partnership and a climate change agreement, either of which an angry China could have undermined. Finally, the administration needed time to brief allies and muster regional support, he said, since the primary point of the operation is to bolster local countries and the international community against Chinese bullying.

Our congressional sources disagreed. The long delay was frankly “embarrassing,” the Senate staffer said.

“The fact that it has taken so long undermines the legitimacy of the very legal claims the administration claims to be upholding,” agreed a House staffer. “Why would something that is in such indisputably solid legal ground require weeks and months of deliberation, played out in the world press? The administration should never had allowed a gap in these ops….This should be an absolute nothing-burger, allowing ships in innocent passage to conduct operations that had been done for decades until 2012.”

Innocent Passage & Military Activity

And this should not be a on-off event. “It has to be something that you do regularly, or regularly enough that you establish a legal precedent,” Clark said. With the significant exception of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea — which the US hasn’t ratified but abides by nevertheless — international maritime law is largely a matter of precedents, customs, and norms, which freedom of navigation operations aim to establish.

“It can’t be just one entrance [into disputed waters],” Dean Cheng said. “It will have to be a sustained policy, and whether or not the decider in chief recognizes that is a question.”

“The United States needs to make these operations routine,” agreed Patrick Cronin.

Then there’s the question of what, exactly, the operation should include. The simplest form of freedom of navigation operation is to sail through a body of water directly from point A to point B, without changing course to nose around or conducting any specifically military activity: This is exercising what’s called the right of innocent passage.

The Chinese are cranky about “innocent passage.” They often take offense at any foreign military vessel passing through their territorial waters without prior permission. But in the case of the South China Sea, just asserting the right to sail through may not be enough. That’s because international law, as most nations interpret it, allows innocent passage even through territorial waters, that 12 nautical mile zone around their shores. So if the US just sails past Chinese-built artificial islets without doing anything else, that’s perfectly compatible with China’s claims that the islets are sovereign territory.

“If US ships … just drive through and demonstrate innocent passage… that doesn’t say whether those islands are real territory or not,” said Clark. To make a clear statement that the islets are not Chinese territory and the 12 miles around them are not Chinese territorial waters, the US forces have to conduct some kind of non-“innocent” activity.

This doesn’t have to be much, said Bonnie Glaser: “One option is to loiter in the area of 12 nautical miles for a period of time, not just travel from Point A to Point B, but spend an hour or two, or maybe go around the island.”

More likely, however, is some kind of explicitly military activity. The Reuters story says a US destroyer will be shadowed by a P-8 Poseidon surveillance plane. “Having the surveillance [plane] is certainly a military activity in and of itself,” said Glaser. “If it’s accompanied by a P-8, that would check that box. The ship itself wouldn’t have to do anything additional.” [UPDATE: This seems to be the approach actually taken Tuesday morning]

If a ship were not accompanied by aircraft, it would need to conduct some unmistakably military activity: deploying its towed-array sonar to practice hunting submarines, for example, or launching a helicopter to look around.

A Chinese Navy J-11 fighter buzzes a US P-8 Poseidon surveillance plane off Hainan Island in August 2014.

What Would China Do?

In geopolitics, for every action there’s a reaction, but not necessarily an equal one. “What are the Chinese options?” Cheng asked. “Everything from ignoring us entirely… to dangerous frankly seamanship [such as] stopping directly in front of a US ship.” Actual shooting is not on the menu.

[UPDATE: The Chinese were swift to denounce the US action, and it said it tracked the Lassen. A Chinese vessel — reportedly the destroyer Kunming — may have shadowed the US ship. On social media, Chinese nationalists were quick to denounce their government’s response for being too weak.]

Ignoring the Americans has its attractions for Beijing, especially if they don’t think the Obama administration has the guts to sail by their islets more than once. “The Chinese may say ‘look, yeah, you came through one time, ok,'” Cheng said. “‘We’re ignoring you because, guess what? It’s still ours.'”

Restraint may play better with international audiences than with Chinese nationalists at home. “I can’t believe they’re going to threaten US forces, but they’ll do something to be able to tell their people they responded to the US provocation,” said Clark. “They’ll turn on fire control radars or they’ll make belligerent threats.”

“At a minimum, they will shadow the US ships,” said Glaser. “They could try…to force the ship out of their waters, [as in] the Impeccable incident several years ago, [but] that’s of course potentially risky business: You could end up with a collision.”

Typically, in territorial disputes, Chinese Coast guard vessels take the lead while PLA Navy warships, much more heavily armed, watch from a distance. Sometimes, ostensibly civilian craft such as fishing boats conduct the most aggressive maneuvers, no doubt out of a pure excess of patriotism without any guidance from Beijing. This three-tiered approach means the heavily armed PLAN vessels are present but aren’t conducting the riskiest actions, like ramming or shoving another ship, that could quickly lead to escalation. Chinese military aircraft, by contrast, have come dangerously close to US planes.

“My understanding is that Xi Jinping is pretty serious about avoiding accidents,” Glaser told me. A big difference between what’s about to happen and past incidents is that the US and China now have formal agreements on how to handle them safely: the Convention on Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES), signed last November, and a brand new agreement on air-to-air encounters signed during Xi’s visit in September. “The Chinese have done a pretty good job” adhering to CUES, she told me. The air-to-air agreement is too new to say.

Both those agreements are about to be tested.

The Navy’s never-ending quest for 355 ships: 5 Navy stories from 2024

Ship counts were clearly on the mind of US Navy officials this year as they made numerous plays to bolster the fleet in novel ways.