An orb-weaver spider in its web. (Peter Pearsall photo for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Digital Library)

WASHINGTON — Imagine body armor made from spider silk, three times the strength of Kevlar. Frontline airfields made of self-healing concrete, full of bacteria that grows crystals to fill cracks as fast as they appear, or using cement alternatives grown like coral to simplify supply lines. Tiny, wearable sensors that use microbes to detect natural toxins or biochemical attacks. Anti-corrosive coatings for aircraft or Navy ships. A host of novel medicines.

These are just some of the applications researchers are actually working on in the field of biomanufacturing, the use of biological and biologically inspired processes to build new materials. Today, it’s a young but promising field, with lots of intriguing experiments but little that’s on a commercially or militarily useful scale.

Spider silk is one of the strongest materials in nature, for instance, but you can’t farm spiders the way you do silkworms — while silkworms eat mulberry leaves, spiders will eat each other — so innovators are looking at, among other things, genetically engineering silkworms with spider DNA to produce spider silks instead. (Presumably no one will be getting superpowers from a silkworm bite.)

RELATED: Pentagon teams up with SBA to sweeten the pot for tech investments

So, as part of a wider US government initiative launched by Executive Order last September, the Department of Defense wants to get in on the ground floor to kickstart domestic production — and keep it from moving offshore.

On Wednesday, the DoD released both its Biomanufacturing Strategy [PDF], seeking to boost the “nascent industry,” and a Request For Information (RFI), asking any and all domestic biomanufacturers for data on their technology and its maturity. No foreign firms and labs need apply, the RFI makes clear, although it helpfully notes that Canada counts as “domestic” for purposes of the Defense Production Act.

The new strategy explicitly cites the offshoring of semiconductor manufacturing as a “prime example” of what it’s trying to avoid. Over 60 percent of semiconductors — crucial components of every modern gadget from smart phones to smart bombs — and over 90 percent of the most advanced types are now built in Taiwan, in range of Chinese land-based missiles, which puts supply chains for both the global economy and the US military at the mercy of rising tensions between Taipei and Beijing.

Biomanufacturing could move offshore much the same way, even to the People’s Republic of China itself, the strategy warns. Already, the document says, “many U.S. companies go to the European Union for their biomanufacturing needs, and it is only a matter of time before U.S. companies also go to China.” A recent study on biotech from the thinktank Center for a New American Security likewise warned the US was at “relative disadvantage” to mainland China and risked “ceding American leadership over one of the most powerful and transformative fields of technology.”

While the CNAS study warned against the chilling effect of over-cautious regulation, the Defense Department focuses on a lack of investment, which the Pentagon can provide from its almost trillion dollar budget.

“The United States faces a foundational gap in the ability to scale up bioindustrial manufacturing from laboratory research and development to commercial-scale production due to the insufficient network of pilot-scale biomanufacturing infrastructure to validate a technology or product,” the study states. “While it has been well-established by numerous start-ups, academics, and DoD laboratories that biology can generate products at the bench scale that could potentially fill capability gaps, research is required in scaling-up biomanufacturing to produce at a scale sufficient to prototype these products.”

In short: Forget about mass production — biomanufacturing is still so small-scale that it can’t yet make workable prototypes for pilot projects.

So how much money are we talking about? A “purpose-built pilot production facility costs $100-200 million, [but] the return on investment for private equity does not exist,” the strategy says. The DoD has already helped fund two biomanufacturing sites. BioFabUSA in Manchester, N.H., was launched in 2017 with $80 million from the military and $214 million from academia, industry and non-profit, focuses on making tissues and organs for regenerative medicine. BioMade in Saint Paul, launched in 2020 with $87 million from DoD and $187 million from non-government partners, looks into “a wide array of [potential] products” from solvents to polymers. Then, looking forward, DoD is investing almost $1.5 billion over five years, according to a White House round-up from the fall:

- $1 billion in infrastructure investments to “catalyze the establishment of domestic biomanufacturing industrial base”;

- $270 million for an Army-managed initiative called Tri-Service Biotechnology for a Resilient Supply Chain, looking at applications “such as fuels, fire-resistant composites, polymers and resins, and protective materials.”

- $200 million to upgrade “biosecurity and cybersecurity” across the nascent industrial base — in other words, to prevent lab leaks, hacker attacks, and other dangers both accidental and intentional.

The Pentagon also hopes to link the fledgling industry to customers, “establish[ing] transition partners for early-stage innovations,” that is, DoD agencies able to pick up basic science and move it up the ladder of Technology Readiness Levels.

The Request For Information, handled by the Air Force Research Laboratory on behalf of the Pentagon’s industrial base policy shop, aims to survey the existing biomanufacturing base. While the RFI is careful not to promise anyone funding or contract awards, it’s explicitly aimed at guiding future DoD investments.

“The objective of this RFI is to assess what biomanufactured materials or products can fulfill essential national defense needs and specifically what investment, if any, toward future state production capabilities may be of benefit to the DoD and are addressable by the DPAI,” it says, referring to the Pentagon’s Defense Production Act Investments office.

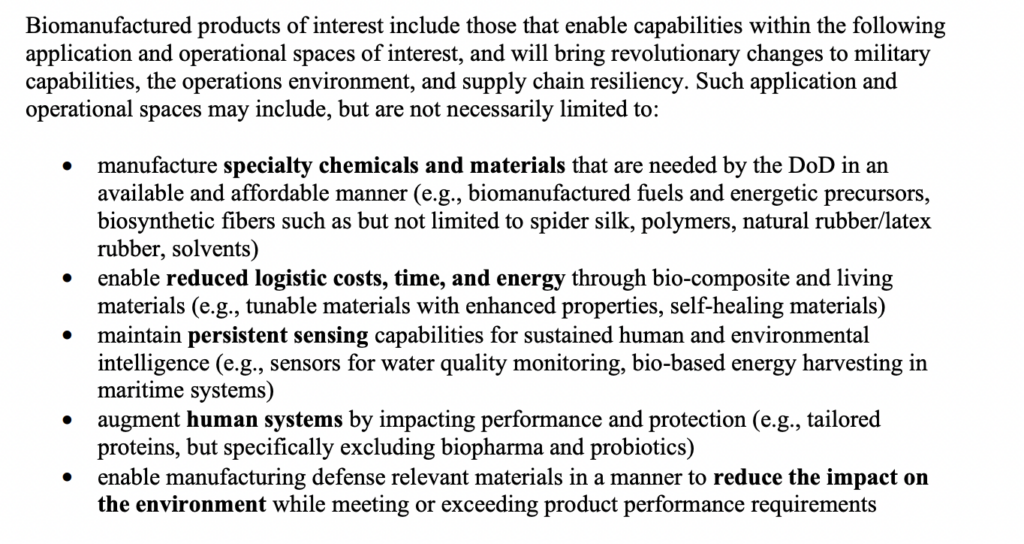

The Defense Department is looking at wide range of biomanufacturing applications, as in this excerpt from the recent Request For Information. (image from SAM.gov)

The scope of the Pentagon’s interest is broad. The RFI asks about everything from biomanufactured raw ingredients — examples include “processed feedstock, enzyme, chemical precursors” — to final products from food items to biocement to sensors.

“Biomanufacturing [is] rooted in medicine and agriculture,” the new strategy acknowledges, but it insists: “DoD must look at biotechnology beyond… medical care and vaccines.” There’s a world of potential applications out there, if the military and the private sector can get this “nascent industry” off the ground.

We fed every 2024 Pentagon briefing into ChatGPT. Here’s what it thought.

The US national security establishment is cautiously embracing generative AI, so Breaking Defense decided to do an experiment.