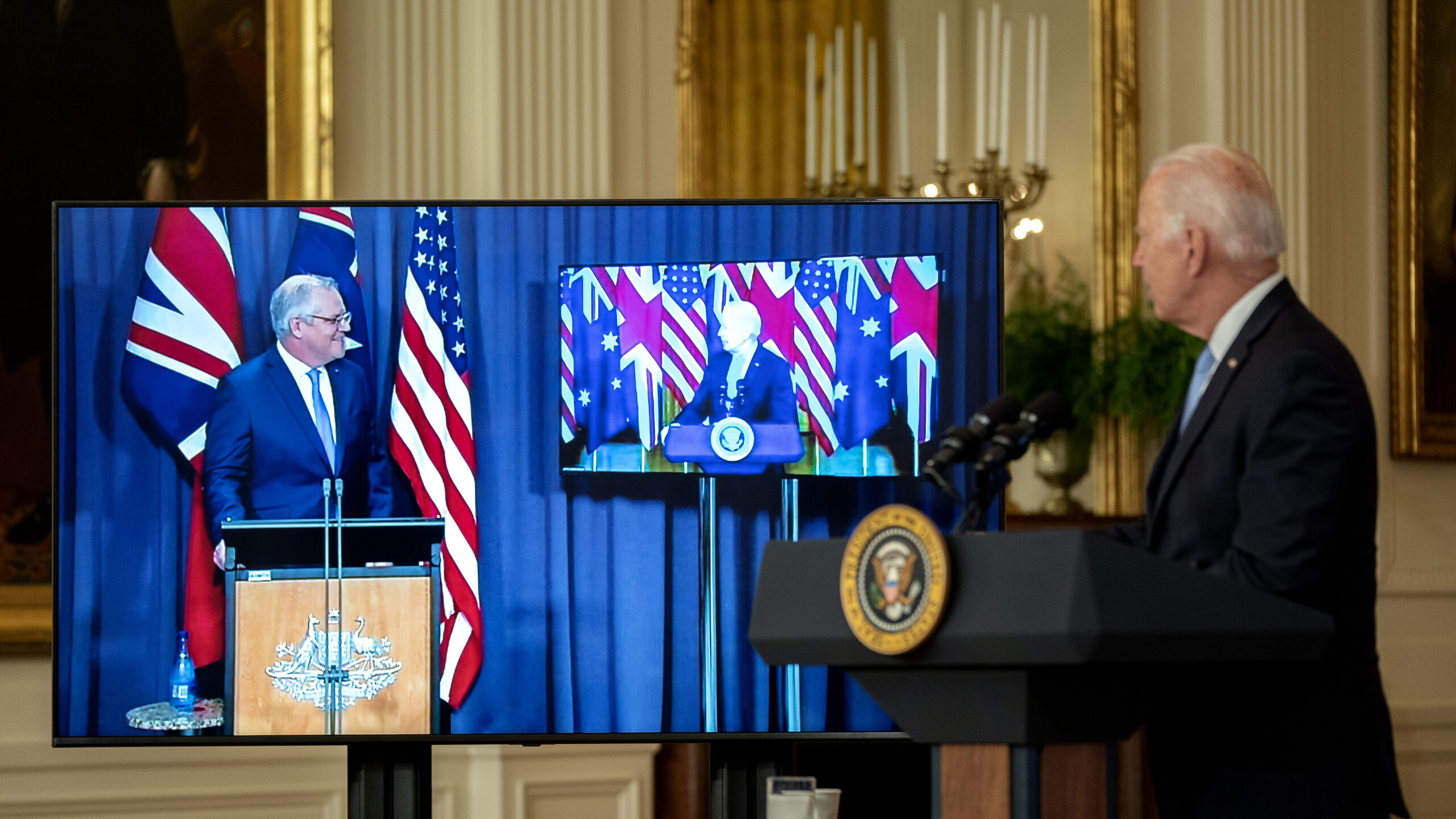

U.S. President Joe Biden listens as Scott Morrison, Australia’s prime minister, speaks via videoconference in the East Room of the White House in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Wednesday, Sept. 15, 2021. (Stefani Reynolds/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Export controls exist to keep US defense technology from falling into the wrong hands — a practical, laudable goal. But in the op-ed below, AEI’s Bill Greenwalt says despite attempts to make it easier for the US to share innovation with its allies, current regulations are strangling the process, endangering the relationships, and security, of the country’s closest friends.

In 2016, Congress changed the legal definition of the US defense industrial base — officially known as the National Technology Industrial Base (NTIB) — to include Australia and the United Kingdom. The late Sen. John McCain championed this expansion beyond the longstanding joint US-Canadian construct to kickstart industrial cooperation between the US and its closest allies. This invigorated NTIB was primarily designed to encourage technology transfer reforms that would incentivize and enable greater defense innovation.

Six years on, the NTIB concept is at risk of failure. While progress has been made in some areas such as coordinating foreign investment reviews, little has been done to harmonize export control processes that are one of the root causes of DoD’s growing loss of technological dominance. Despite the promise of NTIB, an outdated technology control system continues to reinforce US technology stagnation rather than enhance security and innovation.

Congress once again needs to step in and re-invigorate the NTIB by strengthening its mission and explicitly attacking barriers to cooperation and timely development. This should start with expanding the Canadian ITAR exemption to the rest of the NTIB and then taking actions to ensure that US export control process does not undermine the viability of the AUKUS arrangement with Australia and the United Kingdom.

Expanding the NTIB was designed to more clearly bring in to focus the distinction between the kinds of sensitive information the US routinely shares with its closest allies and the hyper-bureaucratic mentality reigning in the US Department of State with regards to unclassified armaments information. Top Secret and higher levels of classified information can flow freely to these nations under the Five Eyes intelligence arrangement, while there is longstanding nuclear cooperation with the United Kingdom that has now been expanded to Australia through AUKUS. This contrasts with the unending process, red tape, and wasted time that flows when these same countries attempt to work with unclassified information that touches long-ago obsolete defense systems or taints commercial technologies and knowledge that have been tripped up by the International Trafficking in Arms Regulations (ITAR).

While once effectively discriminatory and constrained, US export controls have been overwhelmed by a creeping definition of what constitutes knowledge and hijacked by a one-size-fits-all process that is applied to friends and foes alike. Think about it this way: We can share our most sensitive intel and nuclear secrets with the UK or Australia, but we struggle to share information on conventional systems that have been in use for decades.

It’s not just an annoyance. Rather than protecting and advancing US technology interests, ITAR is now hindering development and providing our adversaries with a competitive advantage.

As it peels back the AUKUS onion, Australia’s new Labor government may find that because of ITAR it had a better deal with the French. Just as the UK has found out [PDF], the operation of nuclear submarines has a creeping ITAR component that hinders effectively addressing submarine maintenance due to unclassified technologies not associated with the classified nuclear power plant (which actually is administratively easier to deal with). AUKUS cooperation on hypersonics and electronic warfare will likely suffer from the same set of circumstances. As a result, AUKUS as a concept may be dead in the water until ITAR is addressed and reformed. Only China can benefit from that turn of events.

Even worse, US security is threatened on a much broader scale as the potential application of ITAR controls have become a barrier to the participation in the defense market by some of the most innovative segments of the US and allied economies. Whether based in London or San Francisco, firms in emerging fields such as AI, robotics, quantum computing, data analytics, and bioengineering fear risking their future viability and commercial sales by cooperating with the US military and potentially getting their solutions “ITARed.” Encouraging this cooperation is absolutely vital to our nation when one considers that 11 out the 14 technologies that DoD’s Chief Technology Officer recently identified as critical to defense are primarily in the commercial, not the defense, sector of the industrial base [PDF].

Working with DoD requires an extensive “lawyering up” to protect underlying intellectual property from being marked by the State Department as an export issue. As with security classification it becomes almost impossible to get rid of an “ITAR taint” as it cascades down to whatever it touches. From a business standpoint, the easiest path to avoid any prospect of an “ITAR taint” is to never work with the US government in the first place – particularly in a joint development process. At its most extreme, companies are being incentivized to develop critical R&D offshore out of the US government’s purview, such as with Boeing’s decision to build the ITAR-free combat drone Ghost Bat in Australia rather than America.

These dynamics are, to say the least, not in the US national security interest.

It was to try and change these underlying negative innovation incentives and encourage AUKUS-like cooperative efforts that the “new” NTIB was created in the 2017 NDAA. The thinking at the time was to use our closest allies as a vanguard to test new ways of controlling technology within a trusted community that could eventually be expanded to segments of the commercial market and to a second tier of other close allies. Ideally, lessons learned from any NTIB export control reform could be applied to a trusted group of firms from Silicon Valley or from, say, Norway or Japan. If we can trust the UK, Australia, and Canada with our nation’s most classified intelligence and nuclear secrets then we should be able to trust them with implementing and testing new arrangements for unclassified information currently controlled under ITAR, and if needed under the Department of Commerce’s Export Administration Regulations.

Unfortunately, that approach was seen as a threat to the status quo and the transactional power wielded by the State Department bureaucracy so any NTIB reforms have been subsequently sabotaged. Whether it was a proposal to apply the Canadian ITAR exemption to the rest of the NTIB, create an NTIB forum to even just begin discussing the harmonization of export controls, or to do anything positive to address the impact of ITAR on US innovation incentives, State has successfully been able to keep any substantive progress from occurring. While once promising, the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 has also done little to change this dynamic or the status quo.

As a result, the US will be weaker militarily as it falls further behind the commercial market, while China can gain better access to militarily relevant commercial technology than DoD. Our closest allies will never be able to step in and help fill this growing innovation gap when they first have to deal with a process that takes months to approve an unclassified license merely to have a discussion about a piece of information that may link to some part that was once used in a decades old military system. Equally, there is no incentive for any of our allies or commercial companies to enter into real transformational co-development with the US government when in essence all they are doing is handing the keys to control their ideas to the State Department.

Information sharing, technology transfer, and cooperation are all about trust and for those countries and entities we trust the most (like Canada, Australian, and the United Kingdom) they can (and do) operate under a different rule set such as the Five Eyes and US-UK nuclear agreements. Future export control reforms should be based on this principle. The NTIB and AUKUS can deliver significant national security benefits for the United States but only if Congress and senior executive branch leadership start paying attention and act soon to remove barriers to cooperation.

Bill Greenwalt, long the top Republican acquisition policy expert on the SASC, rose to become deputy defense undersecretary for industrial policy. A member of the Breaking Defense Board of Contributors, he’s now a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.