One of our primary goals here at Breaking Defense is to try and avoid the madness of the daily news cycle and tell our readers what is really happening, as best as any human can tell at any time. The following explanation by two experienced defense budget experts of what really happened to $28 billion discussed in a recent news story is a classic example of this. Read on to see what our Breaking Defense Board of Contributor Mackenzie Eaglen and her colleague at the American Enterprise Institute, Rick Berger, say really happened to $28 billion of military spending that was supposed to have been lost. The Editor.

Last week, headlines blared with claims that the Defense Department had failed to spend $28 billion in time, forfeiting all that money back to the US Treasury. The story said the Pentagon had “let $28 billion go to waste,” with “tens of billions of dollars unspent” as “time ran out.”

Mackenzie Eaglen

This would be an awesome and scandalous story, were it true. Fortunately, it’s not. Just about all of this $28 billion in taxpayer funds will be spent. What this story really highlights is the arcane complexity of the budget execution process at the world’s largest organization. The Pentagon receives a lot of criticism on many different topics, but this is one instance in which piling on is unwarranted.

The implication of the stories, of course, was that “The Pentagon Literally Has More Money Than It Knows What To Do With.” These stories pulled from a report on the first year of the consolidated Pentagon audit released by the office of the DoD Inspector General, which oversees the annual audits. In fairness to reporters, the Pentagon itself remains unable to effectively communicate, with its spokesman only clarifying that the $28 billion came from a running tally since fiscal year 2013.

Were the Pentagon unable to spend the money provided it by Congress, Capitol Hill would be abuzz. The scene of congressional appropriators finding $28 billion between the proverbial cushions would make Wall Street’s Black Friday look orderly. More seriously, appropriations committee staff keep very close watch on the Pentagon’s execution of government funds to ensure money is not being misused or going unused, which is why the Pentagon has an entire chapter of the Financial Management Regulation dedicated to processing expired funding in a responsible fashion.

Expired Funding is Part and Parcel of the Budget Execution Process

“Expired” funding simply refers to funds that can no longer be used for new contracts. Carrying a small balance of expired funding is a longstanding practice at federal agencies, including the Pentagon, largely to cover unanticipated upward contract adjustments at a future date, as now-Air Force comptroller John Roth explained in 2006 Congressional testimony:

“We cannot write new contracts or start new projects after the account expires. For example, a contract amendment for a cost growth, a price re-determination for example, or claims that are within the scope of the original contract are chargeable to that same account that originally funded the contract.”

There’s no perfect analogue in civilian life, but it’s a bit like leaving money in a bank account you’ve closed so you can cover outstanding checks that get cashed after the account’s closed.

Also, expired funding isn’t an exclusively Pentagon problem. A 2006 investigation by Sen. Tom Coburn of Oklahoma found that $54 billion across the government was expired. The transcript of the subsequent hearing features several executive agency financial officials explaining why they have expired funding balances and how such balances are used. The lawmakers involved are mostly understanding of the flexibility needed by federal agencies, though they all express a desire that both branches of government keep a close on expired funding to avoid Cold War-era budget gimmicks.

How Pentagon Funding Expires

But why do funds “expire” in the first place?

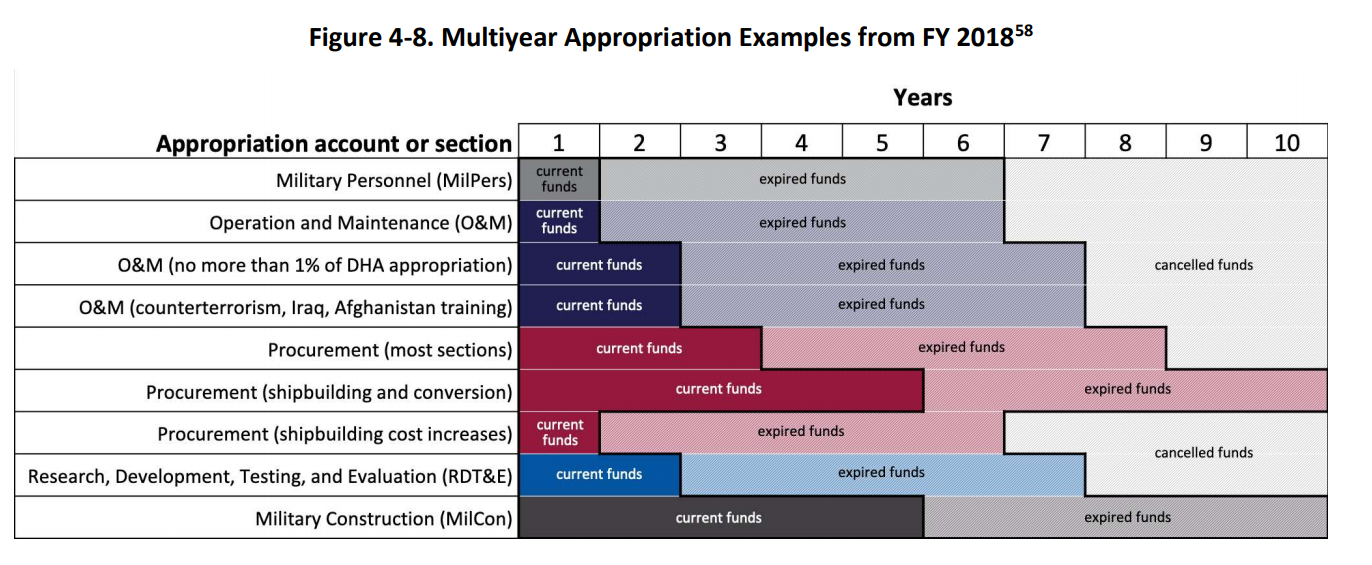

After the Pentagon receives appropriations, it must obligate, or enter into binding contracts, using that money within a certain time period. Some accounts — military personnel and operations/maintenance — are required to be obligated on an annual basis, as the chart shows. Other accounts have longer spendout periods, such as research and development (two years) or shipbuilding (five years).

Source: Section 809 Acquisition Reform Panel, Volume 3, Part 1.

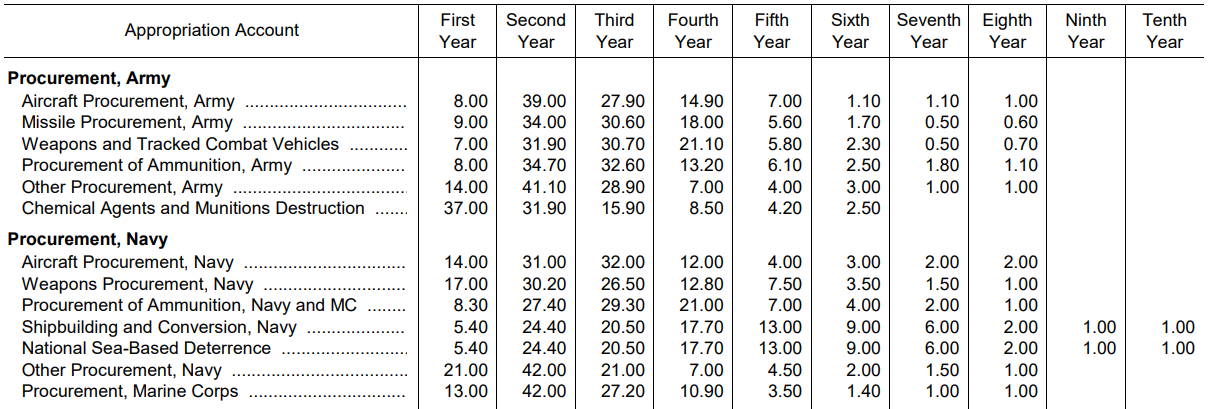

Once the Pentagon obligates money, actually fulfilling the contract can take many more years, as seen below. Some of the money used to pay the contract may become “expired,” meaning it can no longer be used for new contracts, but it can be used within five years to fulfill the contract for which it was originally intended. The chart below shows how long it takes the Pentagon to spend its money. These procurement outlay rates for the fiscal year 2019 budget show that most of the spending will actually occur in 2020 and 2021, and some spending will occur in the late 2020s.

Source: FY19 Green Book Table 5-11

This is at the core of the confusion created by the Inspector General’s report. When the IG rep[ort states that the $28 billion cannot be used for “new” spending, the report is only referring to new contracts. It doesn’t mean the military can’t use the money.

The Pentagon budget request is the combination of millions of individual cost estimates for new contracts, and there’s always a margin of error. In our personal lives, we often find that the contractor’s cost estimates for re-modeling a kitchen or having a car fixed end up being wrong. Among federal agencies, DoD’s combination of massive multiyear projects and very volatile outside conditions make the budget execution process uniquely complex. Unsurprisingly, about 70 percent of the $28 billion expired funds are in the operations and maintenance account, with the rest just about evenly split by percentage across the other accounts. The operations and maintenance account funds a significant amount of very flexible contracts for labor and services, such as refueling or IT work. The cost estimates for those can change drastically due to operational realities, unexpected production difficulties, or wholly exogenous factors. That’s why Congress has built in five years of time for the Pentagon to use expired funding to fulfill contracts it’s already on the hook for.

Expired Funding: A Symptom of An Imperfect Budget Process

Sometimes, of course, the money really does go unused. One way this can happen, per former comptroller and Acting Deputy Secretary of Defense David Norquist, is that “contracts that were awarded for $100 end up getting closed at $97 — $3 stays with the Treasury, so that number slowly creeps up.”

But again, this outcome does not mean the Pentagon “wasted” money or “has more money than it knows what to do with.” It simply reiterates the difficulty of cost estimation.

On a final note, the original news story also intimates that the expired funding resulted from the Pentagon’s inability to spend its fiscal year 2018 appropriations in time because it received its money so late in the year. While giving the Pentagon half the year to do its job is indeed a problem, policymakers should not necessarily suspect that the outcome is expired funding. Rather, the well-known effect of shortened obligation timelines is wasteful use-it-or-lose-it spending, a longstanding problem most recently researched in detail by the congressionally chartered Section 809 Panel.

What the $28 billion in expired Pentagon money really shows, in concert with other conclusions about use-it-or-lose-it spending, is that Washington needs a calm and rational policy discussion regarding the federal budget execution process. There are ways to increase the Pentagon’s spending flexibility while improving congressional oversight, but that discussion can’t begin when the discourse is plagued by misconceptions.

Mackenzie Eaglen is a defense expert at the American Enterprise Institute. Rick Berger, also at AEI, was a professional staffer on the Senate Budget Committee.

Congress unveils stopgap funding bill with $5.7 billion for Virginia-class subs

Congress has until Friday night to pass the continuing resolution before federal spending runs out, giving lawmakers a tight timeframe to move through procedural hurdles and avert a government shutdown.