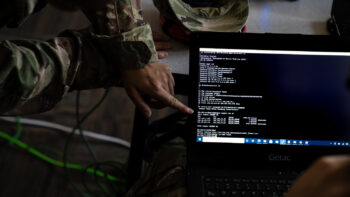

In the Army, David Fastabend urged his fellow soldiers to “Adapt or Die,” as he entitled his essay on the need for innovation — but the principle also applies to the field he now works in, civilian cybersecurity.

With the defeat of the Senate cybersecurity bill last week, one of the crucial unresolved questions is when — or whether — companies should share information on cyber-threats. While the bill would have provided legal protection, Fastabend, who retired as a major general and is now vice president of ITT Exelis, explained to Breaking Defense that fear of liability isn’t the only problem.

“It’s hard on lots of levels,” said Fastabend. “You are very vulnerable under current law to being sued for failure to protect your information. You’re vulnerable competitively to becoming perceived as a company that can’t protect its information.” But, he told Breaking Defense, “you’re also penalized operationally for sharing information”: Helping others defend themselves can actually make it harder to defend yourself.

When you realize your network is under attack, Fastabend explained, it’s natural to think, “I should post this threat to [a] public site, I should share this with everyone. [But] your remediation guys will go, ‘Not so fast: Once you do that, they know that you know they’re in, and they’re going to change their attack profile completely.'” Make an attack public before you’ve defeated it, and you’ve just told the attackers that you’ve on to them — while they’re still in your network and can change their tactics to make themselves harder to root out.

It’s a constant cycle of measure and counter-measure, said Fastabend, not dissimilar from the back-and-forth battle between US forces and the makers of roadside bombs in Afghanistan or Iraq. For one thing, both are rapidly evolving battles where US government institutions struggle to keep up with loosely organized enemies. The military and Congress played catch-up to bombmakers for years, adding ever more armor to protect troops’ vehicles. The defeated cybersecurity bill included proposals for national security standards, but, said Fastabend, “the rule-making process for a standard is 36, 40 months; the technology is doubling every 18 months” (a reference to Moore’s Law): “It’s totally out of synch.”

What’s essential is the capacity not just for rapid reaction to new threats but for rapid adaptation to new kinds of threats. “You’re not trying to hire people just for what they know, you’re trying to hire people for what they can learn. because they get confronted with new situations every day,” said Fastabend. And you can’t just hire twice as many people with half the skill level: “It’s not a volume problem.”

Fastabend, like many cybersecurity experts, argues for a layered approach. The starting point has to be each individual user’s personal responsibility to practice what he calls good “cyber hygiene”: not opening suspicious attachments, not downloading dodgy files, not visiting the weirder corners of the web. But that’s not enough.

“You do your best to keep bad things from getting in, but our bodies don’t completely rely on our skin to keep germs out,” he said, nor should networks rely only on passwords and firewalls. “You’re going to have to assume that there are going to be days when you get sick and you’re going to have to react to it and deal with it.”

That’s where the quick-reaction force of highly skilled cyber experts has to swing into action to defeat the attack. “You have to reverse engineer it,” said Fastbend. “Look at where it’s going, how it’s spreading. It’s not easy.”

Fastabend sides firmly with those who argue that in cyberspace, it’s much easier to attack than to defend. “We’re using a system that was designed as much as possible to not have any restraints on communication… It was not designed from the outset to worry about defense,” he said. “That tends to favor the offense until the system gets redesigned” — not just patched, he said, but redesigned from the bottom up. With government and industry still struggling to find a common approach to cybersecurity, such a fundamental overhaul is a long way away.

From Boeing’s struggles to inflation relief funds: 5 industry stories from 2024

Making a year-end list in which she forces references to Taylor Swift songs for no reason has basically become reporter Valerie Insinna’s favorite Christmas tradition.