Army Secretary Mark Esper addresses the Talent Management Task Force he created to overhaul the cumbersome, centralized military personnel bureaucracy.

PENTAGON: With equipment modernization now in overdrive, Army Secretary Mark Esper is shifting his focus to the human beings that will use the new weapons. In a media roundtable Thursday afternoon, he promised top-to-bottom reviews of both the Army’s cumbersome, centrally-managed personnel system – “my top priority for this year” – and how the force should reorganize for a major multi-domain war against Russia or China.

Esper outlined a long list of initiatives from recruiting to training to electronic warfare. But I’d identify three major lines of effort (my formulation, not his) that will run in parallel and then converge circa 2024, when a new breed of troops will man new kinds of combat units equipped with new technologies: talent & training, concepts & units, and money & modernization.

Army Secretary Mark Esper (blue jacket) does push-ups with soldiers on the sidelines of the Army-Navy game. The military is adopting scientific sports training to develop its infantry like professional athletes.

Talent & Training

The US military’s personnel system is one of the last remnants of Soviet-style central planning. A vast bureaucracy issues promotions and assignments with little regard for where troops want to go, who unit commanders want to have working for them, or who might have special expertise that doesn’t fit in evaluation forms or rigidly defined career paths. An “up or out” promotion system forces experienced operators to get “promoted” to desk jobs — which many of them despise — or quit. But Congress gave the service secretaries new options in the 2019 defense policy bill, and Esper says he’ll make the most of them.

“We’re going to move away from ‘up or out’ [to] perform or out,” Esper told reporters. Instead of a central bureaucracy, he went on, “it is going to be a market-based system where talent is managed at echelon” – that is, by the units themselves. “[We’ll still] centrally manage the top 10 to 15 percent and the bottom 10 to 15 percent,” he said, “but otherwise we can create a marketplace.”

Army Secretary Mark Esper speaks to soldiers at the National Training Center on Fort Irwin, California

If you match those percentages against the Army’s current strength by rank, it suggests that the bureaucracy will still determine most assignments for privates (paygrades E1-E3), who don’t have much of a track record yet, and that there’ll also be high-level oversight of candidates to become generals and sergeants-major. But most people in between will be able to compete for the jobs they want and actually have to impress the people they’re going to work for to get hired, just like in the civilian world.

“That’s happening now” in pilot projects, Esper added. “There’s a fairly good percentage of officers today who are able to go online and looks at what’s out there … but we need to make that the standard throughout the Army.”

Esper already created a talent management task force last year, led by Brig. Gen. Joseph McGee, which briefs him “every six weeks or so.” Now, he’s ordered McGee & co. to prepare him a preliminary slate of options by April 1st. “My ambition,” Esper said, is to craft a comprehensive plan over the summer and fall, then issue a public order to start implementing the reform “by the end of this year.”

Esper has already begun reforms of Army training, cutting out busywork and redundant briefings while adding more time for physical fitness, weapons and tactics. Last year, he launched a pilot program to extend basic and advanced training for new infantry soldiers from 14 weeks – the standard for the past four decades — to 22 weeks, a 57 percent increase. This fall, Esper visited the pilot training program at Fort Benning and came away “very impressed” by the recruits’ physical fitness and tactical skill in live-fire exercises.

So this year, the Army will make 22 weeks the norm for all infantry. It will also nearly double the number of infantry drill sergeants, reducing private:sergeant ratios from over 20:1 to 12. And it will launch pilots of extended training for armor and cavalry soldiers, and possibly for artillery and combat engineers.

In a few years, the raw privates who graduate from this longer, tougher combat training will be the corporals (E-4s) and sergeants (E-5s) leading the small teams that are the fundamental building blocks of frontline units. Their senior NCOs and officers will be increasingly chosen from the most motivated and skilled applicants through the new talent management system. And those units will be getting not only new equipment but potentially sweeping changes in how they organize and fight.

Concepts & Units

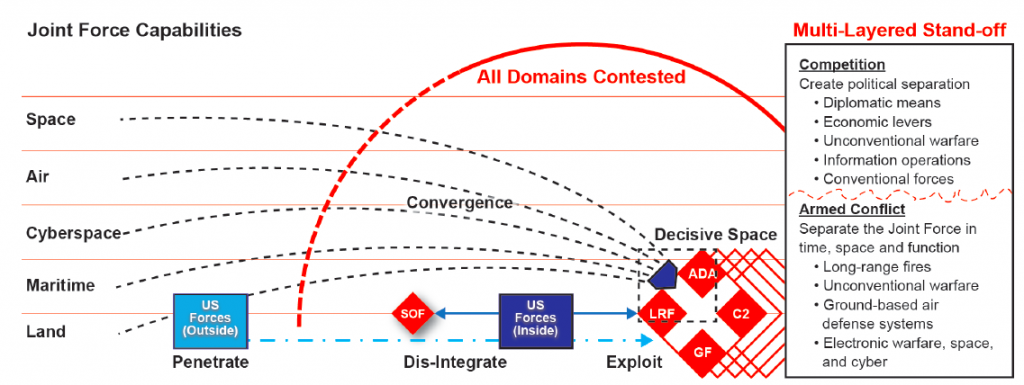

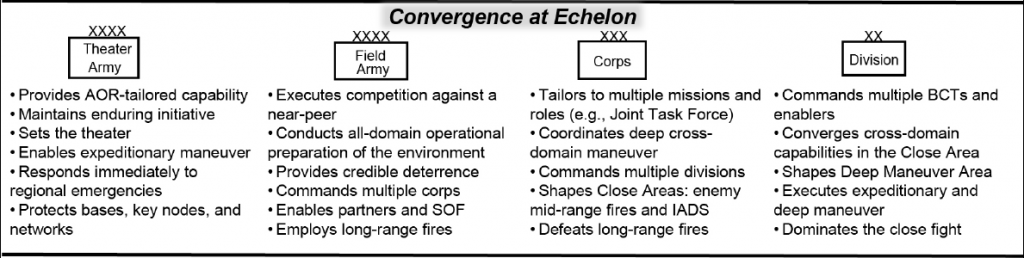

The Army’s already creating new combat units to experiment with future tactics. Most prominently, a prototype Multi-Domain Task Force has been conducting field exercises in the Pacific. The Task Force is built around a conventional artillery brigade, but just this month the Army reinforced it with an entirely new unit, its first-ever Intelligence, Information, Cyber, Electronic Warfare, & Space (I2CEWS) battalion. But there’s much more in the works, Esper said.

The joint Indo-Pacific Command “has been impressed” by the experimental unit, but “that is just one part though of multi-domain operations,” Esper said. “That will involve organizational changes well beyond just standing up a multi-domain task force.”

The Army already knows it needs to rebuild its electronic warfare force and create new capabilities like cyber warfare, Esper said, but it’s still examining whether to increase, for example, artillery and mechanized infantry. “They are running hundreds of simulations trying to figure out what is the right mix of this force or that force, this vehicle, that vehicle,” he said. “They’re going to come back to me in a couple of weeks and give me an update.”

That preliminary report won’t lead immediately to a public announcement of additional experimental units or some wider reorganization, but “that’s all on the table,” Esper said. “Will we be fighting at the brigade level, the division level, the battalion level? Maybe it’s a new level. I don’t thin we should constrain ourselves by history or by how we are configured today. We need to look at the threat.”

“It can be a whole different construct,” he said, “and we have to be flexible enough to recognize that and then courageous enough to implement it.’

Esper’s goal is to get new formations in the field, testing out tactics in the real world. They’ll use surrogates or simulations of future equipment until the actual hardware arrives. What actually arrives and when is the $25 billion question.

Money & Modernization

The human element of warfare is often more important than the weapons – but the cost of weapons is what drives the budget battles. In round after round of grueling reviews – what Army insiders sardonically call “Night Court” – Esper, Army Chief of Staff Mark Milley, and other top officials have delayed or downsized about 100 lower-priority programs and outright cancelled another 80. All told, the reductions hit about one third of the Army’s roughly 500 programs.

The savings freed up about $25 billion over the next five years for the service’s Big Six modernization priorities, albeit more on the backend than the front, Esper said. But the Big Six aren’t spending big money yet, while old programs have constituencies that can complain to Congress.

“We have to make that case to the Hill,” Esper acknowledged. “Many of the programs that we had to either cancel or reduce had merit, had value, but there’s tradeoffs…. I have to get to the Next Generation Combat Vehicle, I have to build Long Range Precision Fires, and something has to give… or I can go ask Congress for an extra $4 to $5 billion a year.”

The Army will keep relentlessly scrubbing its budget – not just for equipment but also training, personnel, installations, et al — “as long as I’m here,” Esper promised. “Night Court is not one time only. Night Court becomes day court. It’s going to become the new normal.”

By constantly shifting money to top priorities in both near-term readiness and long-term modernization, Esper expects the Army to hit a critical turning point in the next four years. On the current course – barring an unforeseen crisis like a war – the Army will reach its readiness goal, having two-thirds of the force at maximum combat readiness at all times, by 2022. At that point, he went on, readiness funding can “level off” and ever more money can start going to modernization programs, just as those programs need to move from relatively cheap prototyping to costly mass production.

“[We’ll] start moving into production in the ‘23-‘24 timeframe,” Esper said. “That’s where you’ll see a lot of output, if everything goes according to plan.”