WASHINGTON: US, Australian, and Japanese marines stormed the beaches and captured headlines, but the most innovative part of the massive Talisman Sabre wargames happened miles inland. To help clear a path for the main landing, two batteries of truck-mounted HIMARS missile launchers — one Army unit and one Marine — were deployed by plane to an austere airfield, linked up with Army attack helicopters and Australian ground troops and staged simulated strikes on “enemy” launchers threatening the amphibious force.

That’s a turnabout from US military tradition, in which it is the air and sea forces that blast a path for ground troops to follow, not vice versa. But with Russia, Iran, North Korea, and most of all China amassing long-range, precision-guided anti-aircraft and anti-ship missiles, American air and sea superiority are no longer assured.

The new Marine Corps Commandant, Gen. David Berger, has said current amphibious forces are too vulnerable. So both the Marines and the Army are looking for new ways to use ground forces — particularly, long-range missiles of their own — to support ships and aircraft.

Multi-Domain Ops in Oz

The complex maneuver in Australia was a preview, in miniature, of the Multi-Domain Operations the US Army envisions for future wars. The Marines have a related, albeit narrower concept called Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations, in which they plan to rapidly deploy long-range anti-ship and anti-aircraft missiles to strategically placed islands in the path of Chinese aggression.

But it’s the Army that has staked its future on the new approach and created a new unit to experiment with it. That unit is the Multi-Domain Task Force, at its core an artillery brigade augmented with high-tech specialists like long-range intelligence and targeting teams. Today the Task Force relies on HIMARS, the High Mobility Artillery Rocket System, but its goal is to develop tactics, organization, and command-and-control networks that can use any available sensor to spot targets for any available missile, not just current US weapons but future and allied ones.

The Army has been campaigning to get the other US services and major allies on board, with mixed success. So it’s significant that this time the Army provided only half the HIMARS launchers and a detachment of AH-64 Apache gunships. Everything else — the other HIMARS, the air transport, the ground security and anti-aircraft defense — came from the Marine Corps, the Air Force, and the Australian Defence Force. In fact, an Australian HQ played a crucial role in command and control of the entire maneuver.

One of the major takeaways from the exercise was that “the Australian Defence Force is able to command and control multi domain operations,” the Talisman Sabre press office told me. “Interoperability between US Army/ US Marine Corps and the ADF is well developed, [and] enhanced digital integration of systems and imagery was achieved, to levels not previously attained.”

Just getting all these disparate forces to the right place at the right time, together, is a feat of planning and logistics: This was the first HIMARS airborne rapid deployment (HIRAIN) exercise held in Australia involving the US Army, US Marines, and the ADF. But getting all these elements to fight as a unified force is an even greater achievement, both technically — getting the radios and networks to connect — and in human terms.

A New Pacific Strategy

“The most impressive aspect of this event is that we did it with the Australian military, whose leaders increasingly view the ADF as having a role in resisting Chinese power projection,” said Bryan Clark, a retired navy strategist. “The second most impressive element is the rapid deployment of HIMARS. This exercise really pushed teams to quickly get to the operating area and move into position, which is what would be needed is HIMARS was to be deployed by US or Australian forces in places like Indonesia, the Philippines, Micronesia, or Papua New Guinea.”

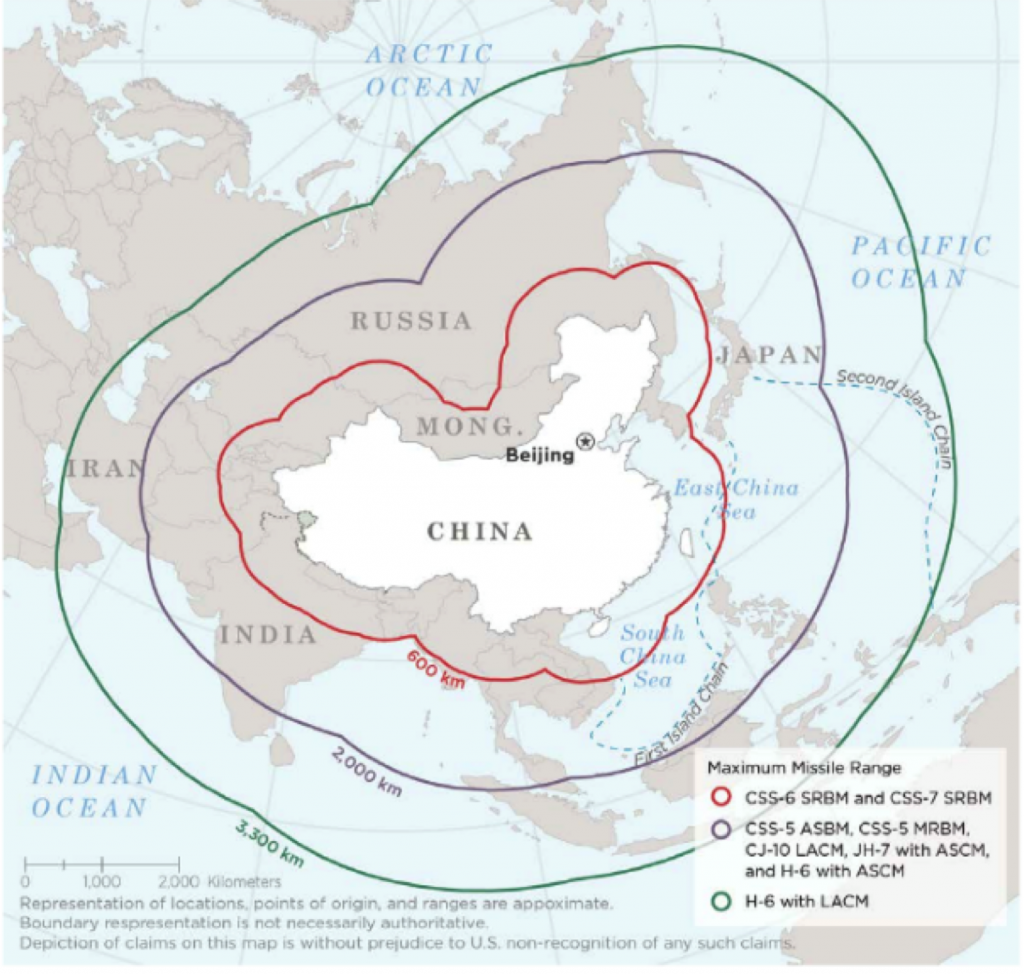

Clark and his colleagues at CSBA — the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments — were among the first to warn that US air and naval dominance could be challenged by advanced Anti-Access/Area Denial defenses. The main striking arm of A2/AD is long-range, land-based missiles, which, while less mobile than the planes and ships on which the US relies, are much cheaper to build and easier to hide. So one of CSBA’s recommended countermeasures was for the US to invest in land-based missiles of its own. (That strategy required ending the 1986 INF Treaty, which banned US and Russia, but not China, from fielding land-based missiles with ranges between 310 and 3,417 miles).

In the Pacific in particular, Clark & co. argued, the US Army and Marines could deploy missile batteries on strategically placed islands to hinder Chinese air and naval advances, just as the Chinese planned to do to the US Air Force and Navy.

“If HIMARS were placed at chokepoints around the First Island Chain” — which runs from Japan through the Philippines and Indonesia down to northern Australia — “they would create a threat that could change PLA [People’s Liberation Army] behavior,” Clark told me. Chinese planes and ships would either have to stay out of range of the US batteries or move cautiously past them, minimizing their radar and radio transmissions to avoid detection. Either alternative would cramp Chinese freedom of maneuver, as well as inflicting casualties. And any Chinese forces dedicated to defending against or destroying the US ground outposts wouldn’t be available to fight the US Air Force and Navy.

Of course, the islands in contention aren’t US territory, so America would need allies to grant it access — and, better yet, to deploy sensors and missile launchers of their own. “We envision the maritime pressure concept that we have been writing about as an allied one, with Japan and Australia playing important roles,” CSBA president Thomas Mahnken told me. “And my understanding is that the Australians are quite interested in procuring their own land-based sea denial systems of their own.”

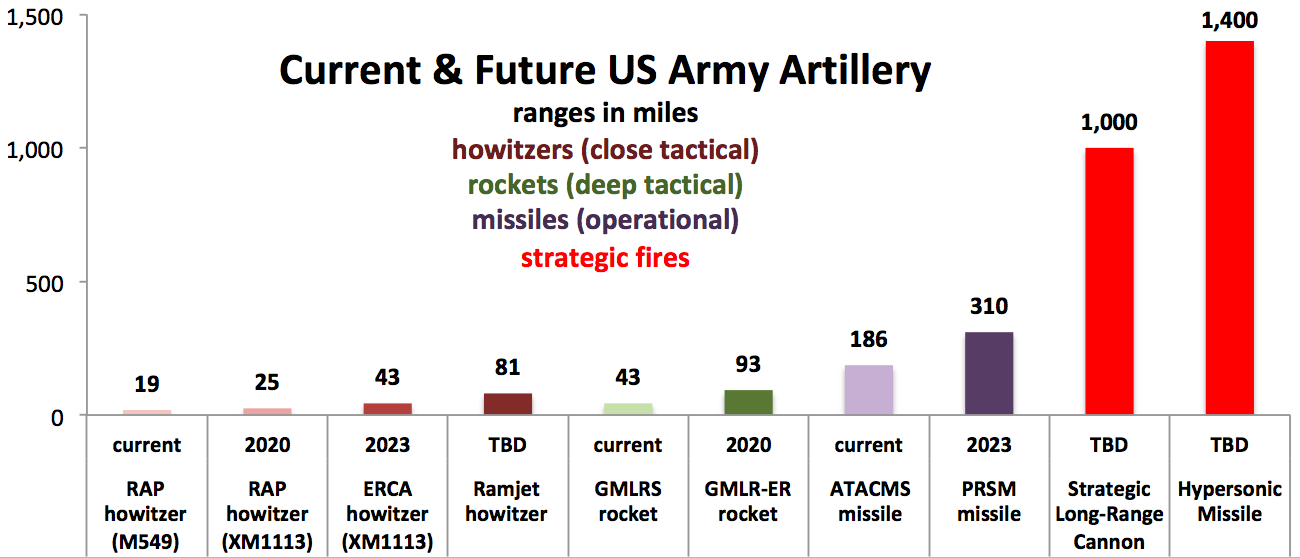

The HIMARS of today, however, isn’t the ideal weapon for this. The long-range weapon it can launch, indeed the longest-ranged missile in the current Army inventory, is the ATACMS, with a range of about 180 miles. That’s a significant distance in Europe but a blip in the vast Pacific. ATACMS is also only designed to strike static targets on land, although an anti-ship warhead has been in the works.

SOURCE: US Army. SLRC and Hypersonic Missile ranges as reported in Army Times.

So the Army is now developing a whole array of what longer-ranged missiles, its top modernization priority. At the low end is an ATACMS replacement, the Precision Strike Missile, to be flight-tested this fall, which will fire from existing HIMARS launchers to ranges of at least 310 miles. At the high end are hypersonic weapons with ranges of 1,000 miles and more. While the larger missiles will require new launchers, the tactics and logistics of employing them will build on what the Army and Marines are already doing with HIMARS in exercises like Talisman Sabre.

“There are any number of munitions in existence or development that could be launched from a HIMARS launcher, and we favor a portfolio approach,” Mahnken said. “The capabilities of the actual munitions in our current inventory are less important than demonstrating the ability to deploy, employ, and redeploy these forces rapidly.”